Filling in the Gutters: Graphic Biographies Disrupting Dominant Narratives of the Civil Rights Movement

Jessica Boykin, Arizona State University

Introduction

The African American civil rights movement of the 1950s and 60s is often used to exemplify the power of social movements and protest to create change. Martin Luther King, Jr has come to represent nonviolent resistance and the dream of racial equality, and his memory has been honored with a national holiday, a monument at the National Mall, and countless local memorials. However, the speeches and biographies of King and other civil rights leaders are often altered to fit progress narratives that tend to erase the networks these leaders worked within and instead promote the sense that these Great Men single-handedly achieved civil rights victories. This move toward progress narratives can be particularly dangerous since memorials and memory narratives that preserve rather than contest memory are less likely to inspire “social action such as protesting, voting, debating, arguing” (Gallagher, 1999, p. 313) and instead promote complacency.

Narratives of the civil rights movement often present an oversimplified and sanitized version as part of what Maegan Parker Brooks (2014) describes as the “conservative master narrative of civil rights history”: “The master narrative’s focus on a few larger-than-life leaders, its emphasis on national victories, and its triumphalist overtones belie the work that remains to be done, conceal the range of advocates with the potential to participate, and mask the ideologies that perpetuate white privilege and continue to disempower African Americans” (p. 4). Rhetorical choices to eliminate certain details from narratives of the civil rights movement are not innocent or harmless but in fact preserve systems of white supremacy.

Beyond the more overt memory artifacts such as museums and monuments, textbooks and popular culture texts promote a narrative that expunges inconvenient details that might challenge the conservative master narrative of the civil rights movement. In his work examining composition textbooks, Cedric Burrows (2017) found that by changing the biographies and even the language of Martin Luther King and Malcolm X, the textbooks remove any offensive (to white readers) language from their speeches, replace informal language to create a more “formal (i.e. ‘white’)” tone (p. 177), and shape King and X to be speakers that represent all of black America (p. 174-5). Thus, when educators do teach students about these leaders, the textbooks are delivering a rhetoric and biography that erases transgressive elements for the sake of keeping white students and teachers at ease.

David Holmes (2013) draws attention to the role of popular culture in memory of the movement, arguing that “because the civil rights movement has long been enshrined in the American imagination, mainstreamed beyond recognition by politicians, popular cultural films, and television from the 1980s to the present, many have forgotten that it was a subversive undertaking” (p. 171). Examining contemporary popular culture texts can reveal how these texts further contribute to or challenge streamlined and depoliticized narratives. Contemporary popular culture texts such as graphic biographies can be particularly enlightening memory artifacts to study.

Examining nonfiction comics like these can lead to a better understanding of the audience’s creative role in public memory and how individual rhetorical experiences are shaped by interacting with public memory artifacts. Public memory scholars (Dickinson, Blair, and Ott, 2010; Gallagher, 1999; Zelizer, 1998; Vivian, 2010; Biesecker, 2002) have demonstrated how public memory projects can challenge grand narratives by cultivating a more complex and nuanced understanding of past events and figures. However, much of the scholarship on the rhetoric of public memory has focused on museums and memorials, rather than popular culture texts. While monuments and museums invite interpretation from the audience, they largely present themselves as whole and try to make a comprehensive statement or provide an accurate account. Comics are radically invitational in their explicitly incomplete construction, as evidenced by the gutters between panels. Conventional memorials typically function pedagogically, while comics situate the reader as a collaborator; this relationship between the audience and author challenges traditional concepts of authorship and provides unique possibilities for interpretation.

In this paper, I examine how the rhetoric of three graphic biographies invites readers to participate in the construction of memory narratives. I begin by discussing the rhetoric of the medium of comics and the rhetoric of artistic techniques in comics. I then rhetorically analyze three graphic biographies to demonstrate how these rhetorical strategies unique to comics facilitate their function as vectors of memory. The first graphic biography, King, written and illustrated by Ho Che Anderson, narrates the life of civil rights leader Martin Luther King, Jr. In the second graphic biography, Malcolm X, writer Andrew Helfer and artist Randy DuBurke tell the life story of Malcolm X, the Black Nationalist leader who is often presented as the counterpart to King. The third graphic biography, March, is written by civil rights activist John Lewis and Andrew Aydin with art by Nate Powell. These three comics challenge the perception of these men as superheroic vigilantes defeating racism and instead depict these highly-mythologized figures as complex individuals working within networks of activists. In depicting the nuances of these leaders, the graphic biographies challenge simplified, conservative narratives of the movement and reveal the relevance of these narratives for contemporary audiences.

The Rhetoric of Closure and Artistic Techniques in Comics

Though there are many styles, genres, and formats of comics, comics share certain traits and conventions, the primary features of which are panels and gutters. Panels are frames that contain the words and images of each depicted moment of a comic, and gutters are the spaces between panels that signify transitions between depicted moments. In a traditional comic, panels and gutters might appear like the image in Figure 1. In this image, each rectangle represents a panel, and the margins between the rectangles represent gutters. In comics, panels are usually filled with images and words, while gutters are left blank.

In comics, gutters represent moments in the sequence that are not depicted by the artist. From a rhetorical standpoint, gutters indicate the need for the reader to cognitively fill in the narrative gaps produced by the gutters to generate a coherent narrative. This “filling in” is facilitated in part by the artist’s use of text and image to encourage a particular interpretation of the content depicted. What is significant about this structure, explains comics scholar Thierry Groensteen (2007), is that it grants the reader choice: she is free to either observe or ignore the interpretative cues provided by the artist (p. 56). This choice makes the reader a collaborative partner in the comics artist’s construction of the narrative. Comics artist and theorist Scott McCloud (1993) echoes Groensteen’s point, asserting that processes of meaning-making and narrative construction in comics provide room for readers’ agency and consent (p. 68-69). Like Groensteen, McCloud (1993) argues that the “audience is a willing and conscious collaborator” with the comics artist as they fill in the gutters with the actions the artist has implied in the scenes depicted within the panels (p. 65). He refers to this process of collaboration as closure in that the work of “observing the parts” of the narrative to “perceive the whole” produces a completed storyline (McCloud, 1993, p. 63).

Figure 1. Sequence of panels and gutters.

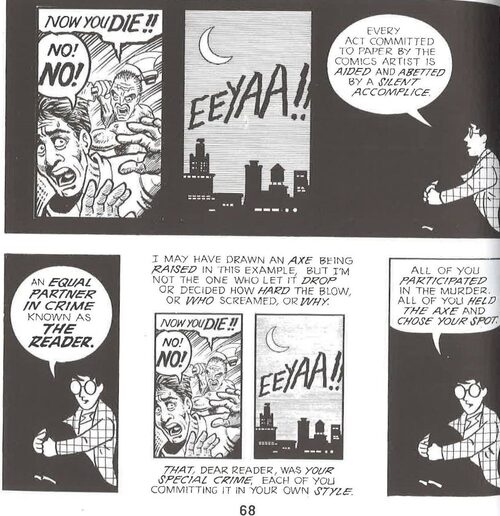

In a sequence of two panels, McCloud demonstrates how a reader might perform closure when reading a comic (see Figure 2). In the first panel, a man wielding an axe shouts “Now you die!!” while the man in front of him holds his arms up defensively. The second panel depicts a nighttime cityscape with large bold letters spelling “EEYAA!!” across the sky. The reader will likely interpret from the artist’s cues that the man wielding the axe is murdering the man who shouted no causing him to scream (“EEYAA!!”), even though the murder is not explicitly shown in the second panel.

Figure 2. The process of closure. McCloud, S. (1993). Understanding Comics: An Invisible Art, p. 68.

Artistic Techniques in Comics

Beyond the rhetoric inherent to the dynamic of panels in gutters in comics, artistic techniques provide additional rhetorical elements. Artistic techniques are rhetorical in that they can significantly affect the way the reader reads a comic. Narrative disruption is a common rhetorical technique in comics that interrupts the reader’s anticipated narrative flow with the effect of driving them to reflect on previous material. Each interruption in the comic has the potential to make the reader more aware of their presence in the co-creation of the narrative. The effects of narrative disruption are especially profound in comics because comics have a relationship with time unlike other mediums such as photographs, film, and alphabetic text. Panels in a comic vary in their representation of time due to their shape and the way elements like sound, dialogue, and motion are depicted within the panel (McCloud 27). Time has an important function in public memory narratives, as “sequentiality, linearity, and chronology, become used up as resources for the establishment and continued maintenance of memory in its social collective form” (Zelizer, 1998, p. 222). Comics artists use techniques that can challenge the structure of time and an overall sense of linearity in the comics narrative. Through certain artistic techniques, the authors can emphasize or overlook certain moments in the narrative. These techniques demonstrate how artists contribute to the production of memory as they select what is remembered and what is forgotten.

Braiding

In The System of Comics, Groensteen introduced the term braiding to describe a visual technique similar to a frame in prose narratives. Braiding creates “webs of interrelation” (Miodrag, 2013, p. 134) by repeating a technique throughout the text, which can sometimes involve a secondary narrative (Groensteen, 2007). Braids are associations in the network of panels of the entire comic that go beyond the parameters of strictly linear storytelling as panels echo those the reader has encountered before. Though it is perhaps only noticed on a second reading of the text, a braid supplements the linear narrative, often providing thematic or narrative depth to a comic. In the comic Maus by Art Spiegelman, for example, the braided narrative is of the author’s interactions with his father while he is writing a comic about his father’s experiences during the Holocaust. In Maus, the braid connects the events of the past to the present, showing contrast as well as the consequences of the events of the Holocaust on the author’s father and his relationship to the author.

Weaving

Readers weave as they move backwards and forwards in the comic to piece together narrative sequences (Postema, 2013, p. 66). Though weaving refers to the reader’s action, artists use techniques that encourage this behavior, often by leaving out or minimizing significant cues and creating a sense of ambiguity that leads the reader to become curious about the events in the sequence. Unlike Groensteen’s concept of braiding, which connects discursive elements of the series to create underlying meaning, weaving deals with the more immediate narrative construction process of the sequence in that it connects sequences of images in the comic to form the story. Weaving directs the reader to previous and/or subsequent panels to perform meaning-making within sections of the narrative. For example, a comic could use this technique if the artist depicts the following sequence: Two friends are sitting on a sofa chatting as the space around them gradually grows darker. Eventually, the characters smell smoke and they panic as they realize flames are overtaking the corner of the room. The reader could return to an earlier panel where they saw one character toss her cigarette in a wastebasket, unknowingly starting a fire.

Figure 3. Conventional panel/gutter structure of comics page.

Breakdown describes the way authors arrange panels on a page, which can strongly influence the way a person reads a comic (Hatfield, 2005, p. 41). A conventional comic book page might resemble the following image (Figure 3), in which the panels are similarly shaped and spaced apart, creating an easy to follow visual narrative sequence from panels 1 to 9.

However, artists often break away from this conventional layout using ambiguity and complexity, which influences how the reader experiences the comic. A common element of a complex breakdown, overlapping panels on a comics page, can “frustrate any sense of linearity, allowing for an impossible and provocative at-onceness” (Hatfield, 2005, p. 51). For example, the artist can use overlapping to show how a person is so busy it felt like she was doing ten different things in a single moment. The authors of Waitress use this technique when they situate the waitress’s body over multiple panels on a page, showing how she seemed to be in multiple places at once since she was such a quick and able server (Hatfield, 2005, p. 51).

Artistic Techniques in King, Malcolm X, and March

King

In describing the way Martin Luther King is remembered in contemporary America, Keith D. Miller (2012) writes that “through some strange alchemy, many now remember the most controversial figure of the 1960s— a decade overflowing with controversies— as little more than a walking marble statue or an African American Santa Claus” (p. 23). Ho Che Anderson’s comic King challenges simplistic and sanitized portrayals of King through its depiction of events in King’s life from the bus boycotts to his efforts in Chicago to his assassination in Memphis. While the comic focuses on King’s time active in the civil rights movement, it also explores King’s private life, which shows King was capable of human error—unlike his mythological image. Anderson writes about King’s conflicts within the civil rights movement, revealing not only King’s complexity but also the complexity of the movement. As the comic reveals these more and less familiar events in King’s life, the details in the narrative go beyond the frequently celebrated quotes and moments of his legacy to portray King’s more complicated angles such as his infidelity and pride, along with his resolute nature and political insight.

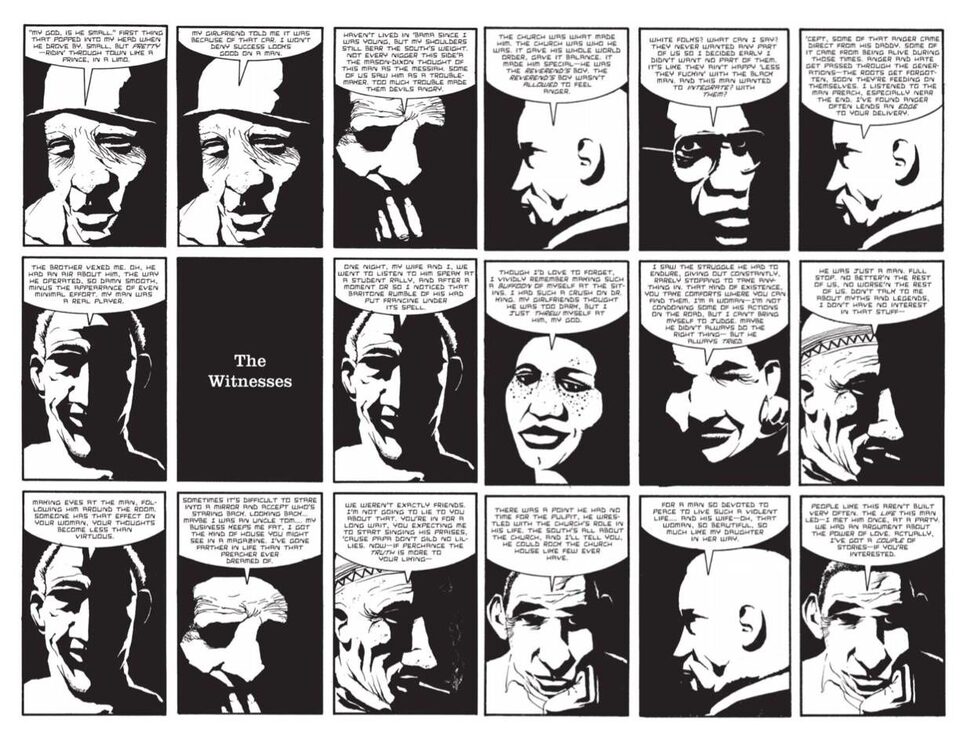

Anderson uses the artistic technique of braiding as he incorporates witness testimony throughout the comic to challenge simplified and celebratory narratives of King. The witnesses function like a Greek chorus in how they narrate events in King’s life; however, instead of one united voice, they provide a diverse array of perspectives that draw attention to the ways King’s contemporary audience perceived and interpreted his actions. Anderson explains that he used witnesses throughout the comic to “offer a running commentary on the action, sometimes providing context, other times a counterpoint to the unreliable characters who were the story's primary players” (Jacobs, 2006, p. 378).

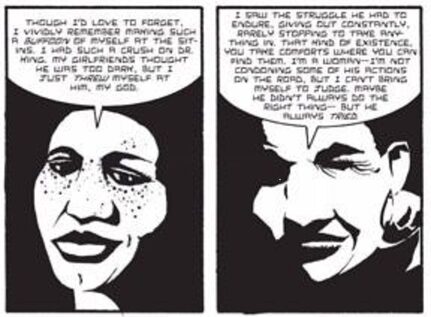

Figure 4. Witnesses. (Anderson, 2005, pp. 8-9).

The witnesses catch the reader’s eye, standing in contrast to other panels in the comic. This is due to the fact that they seem to be frozen in time; their visual depiction, even when they are portrayed in a sequence of panels, is a static portrait. This has an effect similar to a voiceover in a documentary, where the filmmaker puts a photograph of the speaker on the screen while the audio of their voice plays. However, while in a film, the static image could be accompanied by a steadily playing audio, with a comic, the reader must cooperate in order for time to continue; this factor, combined with the fact that both the image and the written text must fit into a panel, means that in the comic, Anderson needs to use multiple panels to deliver the verbal content. Consequently, this technique highlights his choice to keep the speaking character a static portrait, since in depicting them in multiple panels, the reader senses time passing and could conceive that the person is interacting with them, telling their story directly. However, Anderson has created a sense of recorded testimony as opposed to witnesses directly speaking to the reader. Drawing attention to this artistic technique creates the sense that the comic is compiled from many interpretations of King, further inviting the reader to participate in interpreting the events of the narrative.

There are nine different witnesses introduced in the eighteen panels of the comic following the title page, all of whom present different impressions of King. The first panel portrays Witness 1, a person whose face is brightly illuminated to show deep lines around their eyes, saying, “‘My God, is he small.’ First thing that popped into my head when he drove by. Small, but pretty—ridin’ through town like a prince, in a limo…My girlfriend told me it was because of that car. I won’t deny success looks good on a man” (Anderson, 2005, p. 8). In the third panel, Anderson introduces Witness 2 whose face is almost entirely obscured by shadows. Witness 2 says, “Haven’t lived in ‘Bama since I was young, but my shoulders still bear the South’s weight. Not every [n-----] this side’a the Mason-Dixon thought of this man as the Messiah. Some of us saw him as a troublemaker. Too much trouble made them devils angry” (Anderson, 2005, p. 8). The reader is immediately challenged by these first two witnesses as their depiction as static portraits defies the typical panel-to-panel transitions of comics, but more importantly because their clashing descriptions of King—and not particularly flattering descriptions of King—challenge the reader’s ability to create an easy linear narrative.

Figure 5. Two women witnesses. (Anderson, 2005, p. 9).

Anderson takes a risk by providing the reader with multiple perspectives rather than promoting one version of the truth. Some of the witnesses are unreliable and some of them even express hatred, but the witnesses cumulatively function to challenge the way society has thoroughly mythologized King’s life. Anderson even includes the perspectives of white supremacists whose shockingly racist monologues demonstrate the blatant racism of some of the witnesses of King’s life. However, most of the witnesses are more moderate and demonstrate through their testimony nuances of King’s actions and people’s perceptions of those actions. For example, the fourth witness introduced in the comic says, “We weren’t exactly friends. I’m not going to lie to you about that. You’re in for a long wait, you expecting me to start singing his praises, ‘cause papa don’t guild no lilies. Now—if perchance the truth is more to your liking—” (Anderson, 2005, p. 8). This witness is perhaps representative of the general attitude of the comic, which doesn’t hold back from exploring King’s vices but still captures the power of his rhetoric and the strengths of his character. By giving the reader a lens to observe and respond to the environment surrounding King, Anderson invites the reader to gain a better understanding of King’s attitude and behavior through the witnesses’ testimonies. Presenting the witnesses this way shows the controversial response to King and the radical nature of his actions—controversy currently obscured in the national memory of King.

Anderson’s rhetorical strategy of including recurring witness sections in the graphic biography is an example of the artistic technique braiding. The witnesses reappear throughout the comic, but they are not necessary for tying together sequences of panels in the main narrative; in fact, the witnesses braided throughout the comic disrupt the narrative to create breaks in the text. By braiding these witnesses throughout the narrative of the graphic biography, Anderson reminds the reader of the people involved with the events in the narrative who experienced the depicted events directly or indirectly. Anderson’s presentation of the witnesses side-by-side with none of them elevated or emphasized suggests that there are multiple ways of remembering King, since the witnesses provide diverse and often contradictory perspectives. This in itself challenges the monolithic remembering of King and his legacy. Presenting the witness testimony in this inclusive way, Anderson highlights his own standpoint and the tension between objectivity and subjectivity in memory texts like biographies.

Malcolm X

Helfer and DuBurke’s graphic biography, Malcolm X is only about 100 pages long and covers X’s entire lifespan; consequently, it is not as thorough as the other two graphic biographies examined here. Half of the graphic biography focuses on Malcolm X’s childhood and time in prison, while the second half of the comic tends to X’s work as an activist. Because Malcolm X is written in a more traditional comic book style—with onomatopoeia, standard quadrilateral panels, and a focus on action—the unusual elements of the comic stand out.

One rhetorical technique Helfer and DuBurke use in Malcolm X is out-of-frame action sequences. Mainstream comics tend to capitalize on action sequences by drawing them out and zooming in on and exaggerating the effects of violence, but Helfer and DuBurke frequently opt to leave out moments of violent action. Instead, the authors often show only the instrument of violence—such as a gun, an arm wielding a baton, or some other force—or they only portray the perpetrator or victim before or after a violent act rather than showing the violent action as it occurs. These techniques create an opportunity for the reader to construct the implied moments of violence from the cues provided by the author, often having to move back through the comic to piece together information presented in previous panels.

Figure 6. Murder of Ronald Stokes. (Helfer & DuBurke, 2006, pp. 67-8).

In this narrative sequence depicting the police murdering Stokes and assaulting other NOI members, Helfer and DuBurke disrupt the flow causing the reader to weave to perform closure. Helfer and DuBurke’s narrative sequence provides the reader with enough information to infer the cause and/or outcome of the violence while at the same time requiring them to imagine those moments of violence for themselves. To do this the reader must move backwards in the sequence of panels to fill in undepicted moments that are explained later. The reader’s motion through the sequence distinguishes comics as a medium in the way the reader is invited to interfere with the linear sense of time. While constructing a coherent narrative from the panels in the comic, the reader performs retroactive resignification as “details in previous panels become important (again) or come to signify in different ways” (Postema, 2013, p. 66). The readerly process of retroactive resignification has multiple effects, as illustrated above in the sequence depicting Stokes’ murder in Figures 6 and 7. First, it creates tension as the reader is torn away from each escalating scene to move to the other scene. Second, it compels the reader to fill in parts of the narrative not depicted in these respective scenes, such as the moment Stokes was shot and the undepicted moments in which the NOI members were beaten and arrested by the police.

While weaving is a common element of any comics narrative, the process of weaving in Malcolm X is unusually pronounced in violent moments and draws attention to the reader’s role in narrative construction. This technique elevates the reader’s role in a significant way as they can then participate in the remembering of important historical events. Because weaving often results from artists omitting or delaying scenes in the narrative sequence, the reader must gather evidence from the provided cues to piece together what might have happened during those moments. This gives the reader creative power beyond interpretation in that they are not simply understanding the author’s message or the narrative, but that they also actively create moments in the narrative that the author has not depicted. Through this work, the comic challenges the idea that Malcolm X’s story is complete or in the past and instead connects it to the reader’s contemporary experience.

When the reader makes inferences about what happened in ambiguous or undepicted moments, they connect the cues provided by the author with their own experiences. In their search for a logical explanation for what happened in those moments, the reader assembles the details they have gathered from the author’s cues. For example, in Malcolm X, they saw the police harassing and assaulting Stokes, and they likely have also heard of recent police violence against black men in America. Gathering evidence from the comic and their prior knowledge and experience, they can fill in that the police officer shot Ronald Stokes. Because the sequence prevents an easy linear narrative, the reader must do more work than usual to connect the pieces of the sequence to form a coherent narrative, thus making these moments stand out as both significant and memorable.

Malcolm X expands the reader’s understanding of X because it draws attention to his social political context and connects it to the reader’s contemporary perspective. Rather than portraying his actions out of context, the authors demonstrate the violent injustice of Stokes’ murder before Malcolm X arrived and responded to the situation. As the reader weaves to fill in the undepicted moments of Stokes’ murder and the police assault of the NOI members, the process of drawing from their experience and knowledge helps them connect their social political context to X’s, challenging simplified notions of X and encouraging them to see how these historic events relate to the present day.

March

The March trilogy has become one of the most popular comics taught in high school and college classrooms, following texts like Maus and Persepolis. It was the first comic to win a National Book Award, and Books Two and Three received Eisner Awards. The comic is entirely in black-and-white with art by established comics artist Nate Powell, whose work in March illustrates his familiarity with and mastery of comics techniques such as those explored in the previous sections. March’s reception—as well as its production by a writer who is also a major figure of the civil rights movement—separate it from the other two graphic biographies analyzed here. March has acquired a spot in the canon of comics and in the canon of literature for young adult readers, and its canonical status makes it a particularly interesting text to study through the lens of the rhetoric of public memory.

The trilogy tells the story of John Lewis, who served as chairman of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) from 1963 to 1966. Though Book One does offer some of the biography of Lewis’s early life, most of the trilogy focuses on Lewis’s work in the civil rights movement between the years of 1959 and 1965. The graphic biography builds up to the most momentous event in Lewis’s life, Bloody Sunday, and concludes with Lyndon B. Johnson signing the 1965 Voting Rights Act on August 6, 1965, which Lewis refers to as “the last day of the movement as I knew it” (Lewis, Aydin, & Powell, 2016, p. 244).

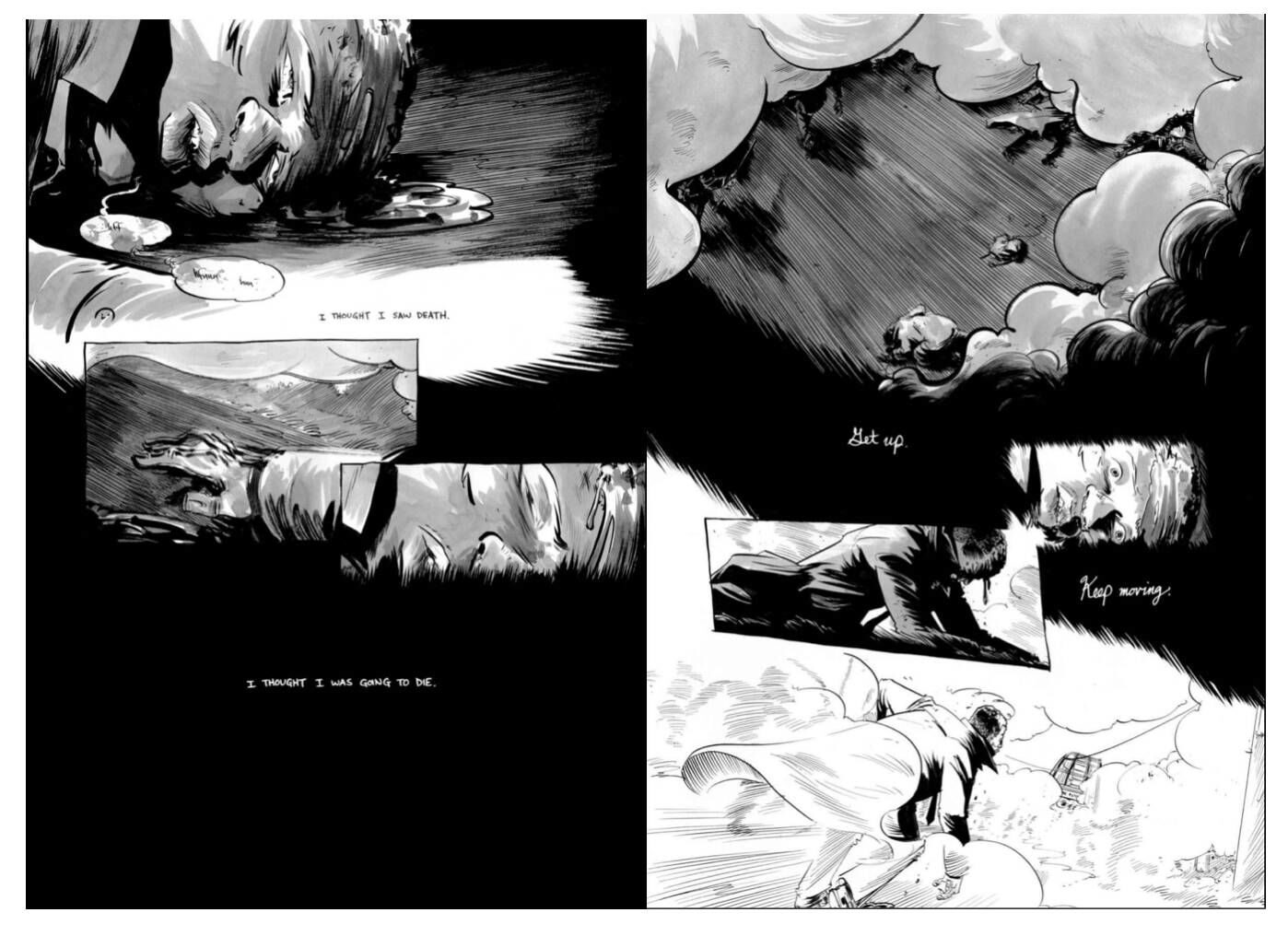

Figure 8. John Lewis struggles to remain conscious and get up on Bloody Sunday. (Lewis, Aydin, & Powell, 2016, pp. 202-3).

In March: Book Three, the authors depict the struggle for voting rights in Selma, Alabama, where John Lewis led hundreds of marchers across the Edmund Pettus Bridge on March 7, 1965, better known as Bloody Sunday. The comic shows the tense confrontation between the hostile state troopers and the nonviolent demonstrators before the troopers attack. The moments of the attack are remarkably wordless apart from the depicted sounds of the batons striking the protestors. Lewis is struck over the head twice, and he falls to the ground, struggling to remain conscious, a scene depicted in a two-page spread (Figure 8).

In the top left corner of the first page, the comic zooms in on Lewis’s face on the pavement. There is blood streaming from his head and pooling on the street, his eyes are rolling back, and he is muttering incomprehensibly. A flash of white stretching across the page narrates from Lewis’s perspective, “I thought I saw death” (Lewis et al., 2016, p. 202). A panel interrupts the white streak on the page with Lewis’s outstretched hand below a layer of spreading tear gas. An overlapping panel shows Lewis’s face, his eyes nearly shut. The bottom-third of the page is heavily inked in black, with simple white text reading, “I thought I was going to die” (Lewis et al., 2016, p. 202).

The top half of the second page zooms out of the scene, showing Lewis’s body on the street. His backpack is several feet away from him and looks disheveled. There are several troopers wielding batons and wearing gasmasks as well as demonstrators running, and a dense cloud of tear gas frames the panel. A thick black wave sweeps below the panel, blending into the dark clouds of tear gas. White script in the black wave reads “Get up…Keep moving” (Lewis et al., 2016, p. 203). A roughly-outlined panel near the center right of the page shows Lewis’s eyes opening wide, his expression alert. In the overlapping, neatly-lined panel below, Lewis struggles to lift himself up as blood flows from his head. The bottom-third of the page is blanched white and shows Lewis walking through the clouds of tear gas, back towards the bridge.

The two-page spread stands out in the comic due to its unusual format, which is significantly different from the conventional layout of a comic page. Through one technique in particular, complex breakdown, Powell uses the page to convey a sense of the chaos and violence of the events of John Lewis’s testimony in a way that evokes the reader’s sensory and emotive responses. This two-page spread in March uses overlapping in the panels towards the center of the page that zoom in on Lewis’s face and body. The overlapping of these panels, along with the fact that the panels are depicting very small but significant actions—such as eyes opening and closing—creates the effect of slow-motion.

This effect of time slowing down is amplified by the overall complex breakdown of the page. The panels are mostly undefined, and even in taking the time to carefully analyze the page, it is difficult to assert how many panels are present in this spread. The four panels that occur in the center of each of the pages resemble conventional panels closely enough to identify them, but the panels at the top and bottom of each page are less clearly defined. There are also fewer visual cues that help the reader determine the passing of time in the sequence, such as dialogue, interaction between characters, or action, and “without language acting as a ‘timer’ or contextual cue for understanding the image, every visual change causes the reader to stop and assess what exactly is happening, and how long it’s supposed to take” (Wolk, 2007, p. 129).

Though the actions in the series of panels are mostly small, Powell has infused the sequence with a sense of violence and chaos. This is in part due to the use of stark contrast, such as the generous use of whitespace on the page, which juxtaposes black and white. The chaos of the moment is imbued in the scene through the indeterminate boundaries between panels which confuse the reader’s sense of chronology, as well as through the odd angles and transitions between panels, such as the panel depicting only Lewis’s hand. The straightforwardness of the captions contrasts with the chaos and ambiguity of the art on the page. Through this technique, Powell brings the reader into the eye of the storm with Lewis as he’s telling the story of how it felt to practice nonviolence while surrounded by violence.

Through this sequence in March, the reader “gains access to a range of processual, sensually immersed knowledge that would be difficult to acquire by purely cognitive means” (Landsberg, 2004, p. 113). While the reader will never be able to fully understand what Lewis went through on Bloody Sunday, Powell’s art takes advantage of the comics medium’s ability to manipulate time, giving the reader a sense of the commotion and resolve of that moment. The reader gains access to Lewis’s perspective as a witness to those moments, as Powell portrays moments that no photo or video could capture in the same way. Working with Lewis, Powell interprets these moments using complex breakdown to manipulate time and create a sensory and emotional connection to Lewis’s memory.

Conclusion

King, X, and Lewis often function as icons of progress, leadership, and human rights. Public memory of these leaders glosses over the intricacies of their lives, focusing on their legacy and ignoring their humanity. Narratives of the civil rights movement often overlook the extensive networks the leaders were involved in, letting the leaders stand for the movement and oversimplifying the work involved in organizing and creating social change. The three comics analyzed in this paper depict the lives of three civil rights leaders in the complexity often excluded from the public memory of their legacies.

The authors of these graphic biographies effectively challenge simplified narratives of King, X, and Lewis through the artistic techniques they utilize in their comics. The witnesses braided throughout King present a sense of the complexity of King’s character that is often left out of memory narratives. The weaving in Malcolm X disrupts the sequence of the narrative in a way that grants the reader greater creative license in reconstructing the sequence to form a coherent story of X’s experiences and better understand his rhetorical situation. The use of complex breakdown in March creates sensory and emotional pathways for the reader to connect with Lewis’s experiences in Selma.

The rhetoric of comics presents a challenge to static notions of history, as the artist and reader collaborate to construct a coherent narrative in real time. The collaborative reader-writer narrative process in comics closely resembles the dialectic between author and audience through which we construct public memory. Public memory projects often embrace, if not encourage, opportunities for the community to actively remember the past (Gallagher & LaWare, 2010). Like other mediums of public memory, graphic biographies recall the past in ways that disrupt concepts of authorship in that they allow for the “supplemental rhetorical activity” of readers (Blair, Jeppeson, & Pucci Jr., 1991). Rather than taking a passive and receptive role, the audience contributes their knowledge to the rhetorical experience of the memory text.

Comics are unique as memory texts due to the explicitly incomplete nature of the medium that is indicated by the gutters between panels that reveal gaps in the narrative. The collaborative meaning-making processes in comics can promote challenges to oversimplified or forgotten elements of history as the reader is granted access to a creative role that encourages them to imagine these undepicted moments. Elevating the reader to a more directly creative role in the interpretation of the narrative, comics encourage readers to use their own knowledge and experience to inform the ways they will perform closure. This process of closure has significant consequences due to the ways that readers will connect the historical events in the comic to their contemporary experience in order to create a coherent narrative, potentially challenging notions that the types of events depicted are isolated to the past and unrelated to current events.

Maurice Halbwachs’ (1952/1992) claim that “the past is not preserved but is reconstructed on the basis of the present” (p. 40) is particularly resonant when studying the memory narratives of contentious moments in history that uncover feelings of guilt and shine a light on America’s troubled past. The way we remember the civil rights movement speaks directly to our values and shapes the way we understand contemporary racial violence and inequality. Due to the collaborative interpretive process inherent to the medium, as well as the artistic techniques that amplify the effects of this process, comics present a unique opportunity to disrupt dominant narratives of the civil rights movement by connecting the moments of the past to the present day, challenging the complacency that comes from believing racial inequality is in the past and instead inspiring social action to address the injustices we face today.

References

Anderson, H. C. (2005). King: A Comics Biography of Martin Luther King, Jr. Seattle, WA: Fantagraphics Books.

Biesecker, B. (2002). Remembering World War II: The rhetoric and politics of national commemoration at the turn of the 21st century. Quarterly Journal of Speech, 88(4), 393-409.

Blair, C., Jeppeson, M., & Pucci, E. (1991). Public memorializing in postmodernity: The Vietnam veterans memorial as prototype. Quarterly Journal of Speech, 77(3), 263-288.

Brooks, M. P. (2014). A voice that could stir an army: Fannie Lou Hamer and the rhetoric of the black freedom movement. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi.

Burrows, Cedric. (2017). How whiteness haunts the textbook industry: The reception of nonwhites in composition textbooks. In T. M. Kennedy, J.I. Middleton, & K. Ratcliffe (Eds.), Rhetorics of whiteness: Postracial haunting in popular culture, social media, and education (pp. 171-181). Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press.

Dickinson, G., Blair, C., & Ott B.L. (2010). Places of public memory: The rhetoric of museums and memorials. Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press.

Gallagher, V. J. (1999). Memory and reconciliation in the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute. Rhetoric and Public Affairs, 2(2), 303-20.

Gallagher, V. J., & LaWare, M. R. (2010). Sparring with public memory: The rhetorical embodiment of race, power, and conflict in the monument to Joe Louis. In G. Dickinson, C. Blair, & B.L. Ott (Eds.), Places of public memory: The rhetoric of museums and memorials (pp. 87-112). Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press.

Groensteen, T. (2007). The system of comics. (B. Beaty & N. Nguyen, Trans.). Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi.

Halbwachs, M. (1992). On collective memory. (L.A. Coser, Trans.). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. (Original work published in 1952)

Hatfield, C. (2005). Alternative comics: An emerging literature. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi.

Helfer, A., writer; DuBurke, R., artist. (2006). Malcolm X: A graphic biography. New York, NY: Hill and Wang.

Holmes, D. (2013). “Hear me tonight”: Ralph Abernathy and the sermonic pedagogy of the Birmingham mass meeting. Rhetoric Review, 32(2), 156-173.

Jacobs, D. (2006). Ho Che Anderson interview. International Journal of Comic Art, 8(2), 363- 86.

Landsberg, A. (2004). Prosthetic memory: The transformation of American remembrance in the age of mass culture. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

Lewis, J., & Helfer, A., writers; Powell, N, artist. (2016). March: Book three. Marietta, GA: Top Shelf Productions.

McCloud, S. (1993) Understanding comics: The invisible art. New York, NY: William Morrow.

Miller, K. (2012). Martin Luther King's biblical epic his final, great speech. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi.

Miodrag, H., & Ebrary, Inc. (2013). Comics and language: Reimagining critical discourse on the form. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi.

Postema, B. (2013). Narrative structure in comics: Making sense of fragments. Rochester, NY: RIT Press.

Wolk, D. (2007). Reading comics: How graphic novels work and what they mean. Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press.

Vivian, B. (2010). Public forgetting: The rhetoric and politics of beginning again. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press.

Zelizer, B. (1998). Remembering to forget: Holocaust memory through the camera’s eye. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.