Sex-Education Comics: Feminist and Queer Approaches to Alternative Sex Education

Michael J. Faris, Texas Tech University

This article argues that sex-education comics serve as sponsors of readers’ sexual literacy and agency, providing an inclusive, feminist, and queer positionality that promotes sexuality as a techné, one that is not merely technical but also civic and relational. These comics don’t solely teach technical information about sex (like anatomy and preventing the spread of sexually transmitted diseases); they also provide material that explores the significance of sexuality in developing one’s identity and in being in relation with others. These comics take a feminist, queer, and inclusive positionality (in opposition to mainstream sex education and to normative regimes of sex, sexuality, and gender), deploy autobiography, prioritize emotions and relations, and provide technical information that shapes the attitudes of readers. Consequently, through the use of multiple modes in comics form, they teach sex and sexuality as a techné—civic practices that are generative of new ways of relating with others and being in the world.

Introduction

Mainstream school-based sex education has come under numerous critiques from scholars and activists for its ineffectiveness and harmful effects on youth. As critics have argued, sex education typically frames sex in terms of danger and risk, positioning youth as needing protection from those dangers and risks rather than treating them as sexual agents in their own right (Allen, 2007; Bay-Cheng, 2003). Further, these programs often reinforce heteronormativity (treating sex almost exclusively as penile–vaginal intercourse) and rigid gender norms. Because most sex education programs depict male sexuality as “individualized and seemingly automatic and unstoppable experiences of desire and pleasure” yet focus on female sexuality as a means of reproduction, they “leave little room for the expression of agency on the part of girls without risk of being labeled as deviant” (Bay-Cheng, 2003, p. 69). The “official culture” of schools often positions students as “‘ideally’ non-sexual”—which “ultimately den[ies] young people as sexual subjects and divest[s] them of the kind of agency necessary to look after their sexual well-being” (Allen, 2007, p. 222). In effect, school-based sex education is too often a pedagogy of “plumbing and prevention” (Lenskyj, 1990) that is de-eroticized, sanitized, and mechanical, ignoring emotions and relationships (Allen, 2007).

In contrast to school-based sex education, comics artists have, since the 1970s, used the medium of comics to educate readers about sex, sexuality, and gender in ways that promote their sexual agency and literacy. These comics encourage understanding sex as a site of pleasure and agency, one that includes the full complexity of lived experiences with sex, gender, and sexuality. Susan M. Squier (2014) has argued that “comics as a medium encourages a broader, more accepting, and distinctly non-normative understanding of human sexuality” (p. 229). Likewise, in this article I argue that sex-education comics serve as sponsors of readers’ sexual literacy and agency, providing an inclusive, feminist, and queer positionality that promotes sexuality as a techné, one that is not merely technical but also civic and relational.

Dale Jacobs (2013) has argued that comics can serve as sponsors of multimodal literacy for readers, teaching them how to navigate “a complex environment that requires interpreting material that is presented in a number of different modes simultaneously and in combination with each other” (p. 170). The comics I discuss in this article are sponsors of what Jonathan Alexander (2008) has called sexual literacy, or “the knowledge complex that recognizes the significance of sexuality to self- and communal definition and that critically engages the stories we tell about sex and sexuality to probe them for controlling values and for ways to resist, when necessary, constraining norms” (p. 5). That is, sex-education comics teach not only technical information about sex (like anatomy, how to use contraceptives, and how to prevent the spread of sexually transmitted infections, or STIs); they also provide material that explores the significance of sexuality in developing one’s identity and in being in relation with others, and they foster a positionality critical of sexual and gender norms, allowing for the recognition and validation of a wide variety of experiences and identities.

I first situate my analysis in a brief history of comics, sexuality, and grassroots sex education, highlighting how sex-education comics arise out of underground comix movements and grassroots activism. From there, I focus on a repertoire of strategies used by comics artists to teach sex education. First, many of these comics take an oppositional positionality to mainstream sex education. Second, this positionality is a feminist and queer one that challenges normative sex, gender, and sexuality, providing inclusive and social-justice-oriented material. Third, in contrast to a “plumbing and prevention” (Lenskyj, 1990) approach to sex education, these comics instead take into account the whole being, working through autobiography, teaching less didactically and more through sharing lived experiences with sex, sexuality, and gender. And fourth, these comics provide relatively easy-to-understand (yet still complex) technical information that is also attitudinal in nature, rather than simply dry and mechanical. I close with a discussion of sexuality as a techné, or a lived set of civic and ethical practices, as it is taught through these comics.

Comics, Sexuality, and Grassroots Sex Education: A Brief History

While a full history of comics is beyond the scope of this article, I provide a brief (and admittedly incomplete) history of comics and their relationships to sex, sexuality, and grassroots sex education.[1] Sex has been a consistent theme and subject matter for comics for the last century. As Hillary Chute (2017) observed, “Comics have long been connected to the sexually taboo—and still are” (p. 103). Darleck Scott and Ramzi Fawaz (2018) have similarly argued, “At every moment in their cultural history, comic books have been linked to queerness or to broader questions of sexuality and sexual identity in US society” (p. 198). Depictions of sex in comics go back at least to the late 1920s when comics artists published (illicitly and illegally) the “Tijuana Bibles,” short eight-page pornographic comics that often repurposed other comics characters and celebrities into sexual adventures (Chute, 2017; Pilcher, 2008).

Historically, though, most comics have not been explicitly sexual in nature (though see Pilcher, 2008, for a history of erotic comics; see also McGurk, 2018, for a discussion of women comic book characters coded as lesbian in early twentieth-century newspaper comics). But they were often tied to sexuality in the public imagination, especially during the moral panic around comics in the late 1940s and ’50s. This moral panic was largely led by psychologist Fredric Wertham, whose articles and 1954 book Seduction of the Innocent argued that comics were corrupting children and leading to criminal deviancy. Sexuality was central to his argument; for example, he charged the famous Batman and Robin duo with being “a wish dream of two homosexuals living together” (p. 190) and Wonder Woman with having a “homosexual connotation” (p. 192) and being a “morbid ideal” for young girls (p. 193). He further charged that comic books were dangerous to youths’ sexual development as they provided “sexual arousal which amounts to seduction” (p. 175). Wertham’s book and his subsequent testimony before Congress about the dangers of comics to youth led to the Comic Magazine Association of America’s creation of the “Comics Code” in 1954. This code provided a series of standards that effectively censored mainstream comics, forbidding depictions that might “create sympathy for the criminal,” show “excessive violence” or nudity, or hint at or portray sexual perversion or illicit sexual acts (quoted in Nyberg, 1998, p. 166).[2]

Underground Comix and Feminist Sex-Education Comix

While the Comics Code prevented depictions of explicit sexuality in mainstream comics, the underground comix movement of the 1960s and ’70s provided an avenue for comics artists to explore sexually explicit themes (as well as other political and social issues, often of a taboo nature). At the forefront of the movement was Robert Crumb and his comics like Zap and Snatch Comics. Crumb’s comix were “openly carnal and scatological” with “detailed drawings of male and female genitals” and subversive content (Chute, 2017, p. 113). Squier (2014) observed that underground comix “challenged the silencing effects of enforced normativity by defiantly imaging and voicing previously taboo personal experiences from defecation, condom use, and the use of sanitary napkins to fornication, masturbation, sodomy, and cunnilingus” (p. 228). Underground comix became a new site of “informal sex education” for many readers (p. 228).

Many women underground comix artists saw much of Crumb’s and other male artists’ work as hostile toward women. While these artists were trying to be politically subversive, feminist artists like Trina Robbins found them sexist and “politically oblivious” to gender and power issues (quoted in Estren, 2012, p. 134). Feminist underground comix artists subsequently created women-centered comics like Wimmen’s Comix (which ran from 1972 to 1992) and Joyce Farmer and Lyn Chevli’s Tits & Clits (1972 to 1987) (Chute, 2010; Robbins, 1999). As Paul Lopes (2009) explained, these comix, by providing feminist perspectives, offered “a more coherent politics in their intervention in the underground comix movement” than other underground comix did (p. 84). Many feminist comix explicitly addressed women’s sexual health and sex education as part of the larger feminist movement that challenged medical and scientific communities for failing to meet the needs of women (Elbaz, 1998). For example, in 1972, Lora Fountain published Incredible Facts o’ Life: Sex Education Funnies, which featured comics about venereal diseases, abortion, and birth control. The following year, Farmer and Chevli (1973/2018) published Abortion Eve, a comic that featured fictional narratives of five women receiving advice on abortion services. Comics, then, became a site of feminist sex-education activism.

The underground comix movement had important influences on future comics by developing new, alternative styles and and approaches to comics, being explicitly political, developing new production and distribution models that weren’t tied to regular periodical publishing, and re-imagining comics as sites of intimacy between creators and readers (Hatfield, 2005). Chute (2017) has attributed underground comix artists like Crumb and his partner Aline Kominsky-Crumb, creator of comics like Twisted Sisters, with pioneering a style of “intimate, body-focused self-expression” (p. 127) that would be implemented by comics artists in the following decades.

Grassroots Activism Sex Education: Safer Sex Comix

These influences helped to shape the sex-education comics I discuss in this article. Before discussing my examples, I turn to another historical example of sex-education comics: Safer Sex Comix, published by the Gay Men’s Health Crisis (GMHC) in 1986. Safer Sex Comix was one of the many grassroots sex educational materials produced by AIDS activists in the 1980s. As Jan Zita Grover (1995) recounted, the stigmatizing rhetoric of mainstream media around AIDS “was countered in gay communities by massive campaigns to affirm the values of gay liberation: resexualizing gay men by redefining sexual pleasure and sexual acts,” often through safer sex educational materials (p. 366–367). By 1985, organizations like GMHC began producing sex-education materials that weren’t solely textual/alphabetic in nature: videos, safe sex calendars, and comics. Grover explained, “All these materials reaffirmed the pleasurability of gay sexuality and gay identity in the face of medicine, epidemiology, and... popular media’s massive assault on gay sexuality” (p. 368).

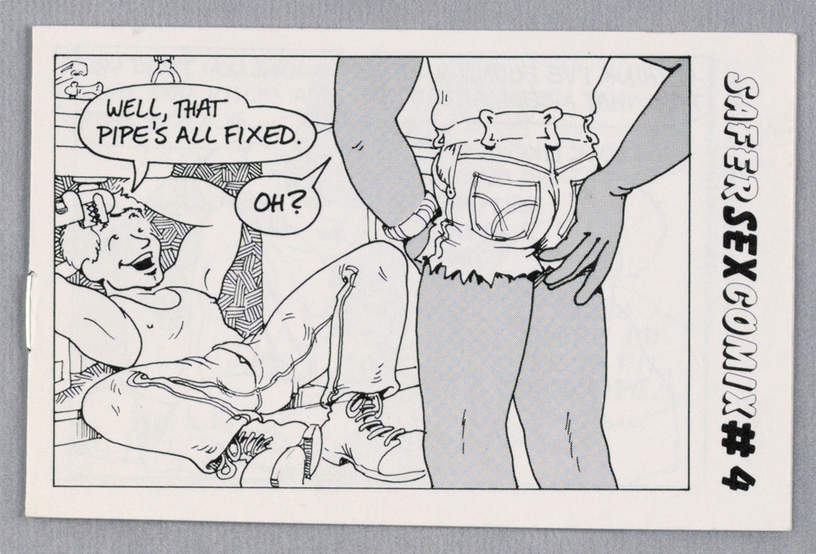

Safer Sex Comix was an eight-page mini-comic (in the style of the Tijuana Bibles), distributed at gay bars by GHMC volunteers called “bar fairies” (Grover, 1988, n6). The comics didn’t shy away from the erotic in promoting condom usage. Issue #4, for example, featured a sex scene between two men, one a plumber who refers to condoms as his “plumber’s helper” (cited in Crimp, 1987). As Douglas Crimp (1987) has chronicled, Safer Sex Comix gained national attention when, in 1987, Senator Jesse Helms responded to its publication by introducing a bill that prohibited the use of federal funds for AIDS prevention materials “that promote or encourage, directly or indirectly, homosexual sexual activities”—a bill that passed by an overwhelming majority of 94 to 2, even though no federal grant money had been spent on the comic (quoted in Crimp, 1987, p. 264; see also McAllister, 1992).

Figure 1: First panel from Safer Sex Comix #4 (1986). Reproduced under fair use.

Alt Text: Comic panel depicting a plumber under a sink saying, “Well, that pipe’s all fixed.” A man wearing short shorts, viewed from behind, responds, “Oh?”

Safer Sex Comix highlights that sex-education comics can be produced and distributed within a broader culture and political climate hostile to the livelihood and sexual health of their readers. As Crimp (1987) concluded in the 1980s, the Helms amendment and other anti-gay rhetoric left queers “forced to recognize that all productive practices concerning AIDS will remain at the grass-roots level” (p. 265). Government-sponsored AIDS education, he observed, was unable to consider “any aspect of the psychic but fear,” despite the advertising industry’s ability to eroticize just about any product—except condoms, it seemed (p. 266). Grassroots comics like Safer Sex Comix were effective because they appealed to the psychic lives of gay men—they encouraged condom usage as an erotic act rather than appealing to fear or educating through sterile, desexualized advertisements.

As with the comics I discuss below, Safer Sex Comix worked as a site of sexual literacy through multimodal rhetoric, including linguistic, visual, gestural, and spatial modes. Jacobs (2013), drawing on the New London Group (1996), argued that comics make meaning not solely through words but also through “visual, gestural, and spatial elements” (Jacobs, 2013, p. 14). In Figure 1 above, the cartoonist depicts an eroticized scene that works through the combination of multiple modes working together. Linguistically, readers encounter a plumber concluding, “Well, that pipe’s all fixed” as the other character responds, “Oh?” This text, however, works for readers (suggesting sexual innuendo) only because it is in conjunction with the visuals—an attractive plumber positioned under a sink, his body open to the second character and readers, and the second character, seen from behind from below the waist, his hand on his own butt cheek and wearing cutoff jean shorts. These visuals work in conjunction with both gestural and spatial elements, eroticizing the moment and leading to future panels that eroticize condom use. The scene becomes erotic gesturally (tapping into both mundane experiences of having a plumber fix a sink and erotic scenes from pornography): the plumber’s open posture reveals emphasizes the bulge of his genitals, and readers voyeuristically look at him, identifying with the gaze of the man readers see only from behind (similar to yet a queer take on classic identification and objectification in film; see Mulvey, 1975/1999). And spatially—“the environmental and architectural space” of panels and page layout (Jacobs, 2013, p. 14)—the comic works through eight panels spread out over eight small pages in the vein of the Tijuana Bibles to narrate a sequence of events that eroticize condom usage as the plumber introduces the other man to his “plumber’s helper” for his “pipe” (see Crimp, 1987, pp. 260–263 for a reprint of Safer Sex Comix #4). Through the combination of linguistic, visual, gestural, and spatial modes, comics like Safer Sex Comix provided an alternative to the sterilized, de-eroticized approach of mainstream sex education.

As I show through my discussion below, sex-education comics are often responses to the limitations of professional sex education. Cindy Patton (1987) has stressed that it is important to remember that sex education was developed by feminist and gay and lesbian activists so that sex education does not fall solely into the domain of medical experts and so that activists can continue to take risks that lead to effective education and changes in sexual practices. (Patton also published Making It: A Woman’s Guide to Sex in the Age of AIDS [Patton & Kelly, 1987], which featured comic illustrations by Allison Bechdel.)

Since the 1970s, comics have been a site of grassroots sex education, often taking an oppositional approach to mainstream sex education and making sex education personal, erotic, and often funny. In the following discussion, I turn to more recent examples of sex-education comics produced over the last decade, showing how they work to sponsor readers’ sexual literacy and promote their sexual agency through their oppositional positionality, use of autobiography and inclusion of emotions, and technical material that also shapes attitudes.

Oppositional Positionality to Mainstream Sex Education

Many sex-education comics take an oppositional positionality to mainstream sex education and to normative regimes of sex, gender, and sexuality. These comics artists and writers understand that mainstream sex education—both formally in schools and informally in mass media and through many families—is lacking because it fails to provide full information, often provides inaccurate information, lacks attention to the emotional and erotic aspects of being sexual agents, and fails to meet the needs of women, girls, and sexual and gender minorities.

Sex-education comics artists often take the limitations and disappointments of sex education (whether at school or in culture more broadly) as an exigence for their projects. For example, in the alphabetic/textual introduction to Not Your Mother’s Meatloaf: A Sex Education Comic Book, Saiya Miller and Liza Bley (2013) situated the need for a sex education comic collection by discussing their own experiences with school-based sex educations. Miller wrote of being segregated by gender for sex ed: “I wondered why we should only have to know about one set of bodily functions” (p. 13). Further, while some of the information she learned was useful, her lived experiences didn’t seem to match up to the “map” provided by sex education: “There were many discrepancies between what I had been told about sex and what I had experienced at that point. I had been thoroughly instructed about the functions of the reproductive system, but I had very little idea of what to expect when it came to my heart and mind” (p. 15). As a response to the limitations of sex education, Meatloaf (as I’ll refer to it) doesn’t provide a traditional sex education experience; it’s not an instructional manual or traditional guide. Instead, it collects over 40 black-and-white comics that explore a wide array of issues and experiences related to sex, gender, and sexuality, often from the perspectives of personal experience. Contributors share experiences about first kisses, body image issues, never having an orgasm, unethical gynecologists, alcohol and sex, STI testing, attending fetish conferences, sex and aging, relationship breakups, and more.

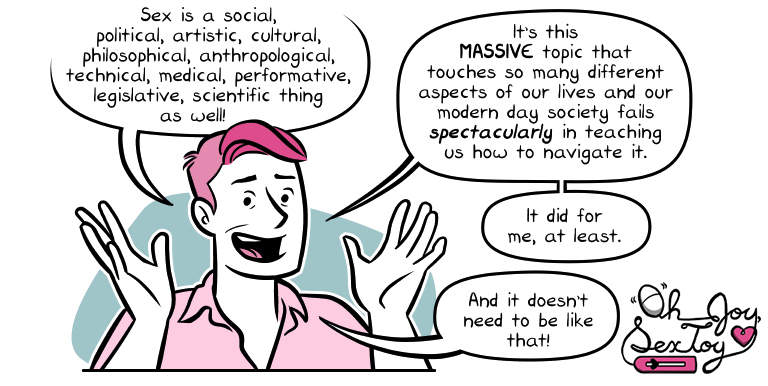

Erika Moen and Matthew Nolan likewise understand their webcomic Oh Joy Sex Toy (OJST, www.ohjoysextoy.com) as fulfilling a need because of the failures of society to adequately educate about sex. Moen’s work in sex-education comics dates back to her 17-page zine GirlFuck, published in 2005, which was “a quick ’n’ dirty introduction to some of the most popularly misunderstood concepts regarding girl-on-girl sexin’” (p. 1). She and her partner Nolan began OJST as a weekly sex-education webcomic in 2013. OJST provides reviews of sex toys in comics form and frequent sex-education comics created by Moen or by guest artists. With OJST, Moen was driven by a desire “to make the sex education that I needed when I was learning about sex. I want this to be a friendly, accessible resource for anybody who’s got questions about sex” (quoted in Anderson-Minshall, 2018). Moen and Nolan have published four print volumes of their webcomics (Moen & Nolan, 2016–2017) and a subsequent book featuring only their sex-education comics, titled Drawn to Sex: The Basics (Moen & Nolan, 2018a), which promises to provide sex positive “comics we wish we could have read when we were learning about these subjects” (Moen & Nolan, 2018b). As Moen explains in the comic announcing the Kickstarter for Drawn to Sex, “Sex is a social, political, artistic, cultural, philosophical, anthropological, technical, medical, performative, legislative, scientific thing,” yet “our modern day society fails spectacularly in teaching us how to navigate it” (Moen & Nolan, 2018b). Moen’s and her guest artists’ comics on OJST explore a wide range of topics related to sex, sexuality, identity, and gender, including explanations of sexual anatomy and health; birth control methods; practices like oral sex, masturbation, and water sports; and concepts and identities like queer, asexuality, and puppy play.

Figure 2: Panel from Erika Moen and Matt Nolan’s (2018b) Oh Joy Sex Toy (www.ohjoysextoy.com) comic announcing the Kickstarter for Drawn to Sex. Reproduced with permission.

Alt Text: Panel featuring Erika Moen explaining in four speech bubbles that sex is complex and touches our lives in many ways, yet “society fails spectacularly in teaching us how to navigate it.”

Sex-education comics, then, take an oppositional positionality toward mainstream sex education, often seeing its limitations as an exigence for their own work. Comics artists respond to these limitations in mainstream sex education—lack of information, failure to take into account full lived experiences, and failure to address the needs of those marginalized in society—by providing information and experiences through the medium of comics, often from a feminist or queer perspective that stresses inclusivity.

Feminist, Queer, and Inclusive Positionalities

The feminist and queer positionality of these comics often takes an inclusive and social-justice-oriented approach to their sex-education materials. As Miller and Bley explained on their now-defunct blog for their zine—which ran for six issues before being compiled into the book Meatloaf (Czerwiec, 2013)—their hope was that these comics would “challenge hetero and gender normative practices in sexuality education” (Not Your Mother’s Meatloaf, 2012). If we understand positionality as the interpretation of one’s position in society—how one is positioned in relationship to others, culture, and power (Alcoff, 1988; Sánchez, 2006)—these comics artists often take a positionality that understands that cisgender women and sexual and gender minorities are often underserved, underrepresented, and marginalized in a society that attempts to deny them sexual agency. These comics artists respond to this marginalization by being radically inclusive in their sex-education comics.

Isabella Rotman (2016b), for example, opens You’re So Sexy When You Aren’t Transmitting STI’s with a discussion of pronouns and the challenges of writing about sexual organs, which carry “gendered connotations” (n.p.). You’re So Sexy is a saddle-stapled print comic featuring explanations of consent, STIs, contraceptives, barriers, and breast and testicular exams—a discussion guided by a character named Captain Buzzkill, a buff man donning briefs underwear and a tight shirt, thigh-high boots decorated with hearts, and a utility belt holding condoms, lube, and dental dams. Rodman’s opening explanation is meant “to prevent anyone from feeling that their sexual orientation or identity has been overlooked” (n.p.), an attempt at making the guide as inclusive for people of all genders and sexual orientations.

Rotman’s other comics are also designed to be inclusive of transgender experiences. She has collaborated as an artist for Dr. RAD’s Queer Health Show (RAD Remedy & Rotman, 2016a, 2016b), a sexual health comic produced by RAD Remedy, a nonprofit that provides health information for transgender, gender non-conforming, queer, and intersex folks. The Introduction to Terms and Disclaimer issue of the comic (RAD Remedy & Rotman, 2016a) opens with the character Dr. RAD, who narrates these guides, explaining that the guides are for everyone, but the focus will be “on people whose gender may be different than what they were assigned at birth, because those folks often find it difficult to find this kind of information” (p. 3). Because many transgender and genderqueer people often use different terms to describe their genitals, Dr. RAD validates that experience (it’s “FANTASTIC”) and explains that the guide will be using the term “BITS to describe genitals and other body parts associated with sex or gender,” though at times for medical purposes they use terms like “penis” and “vagina” for medical clarity (p. 3).

Figure 3: Dr. RAD’s explanation of terminology from the Introduction to Terms and Disclaimer issue of Dr. RAD’s Queer Health Show (RAD Remedy & Rotman, 2016a, p. 3). Reproduced under Creative Commons.

ALT TEXT: Page featuring multiple panels in which Dr. RAD explains that the comic will focus on transgender readers and that she will use the term “bits” to refer to genitals, but will occasionally use medical terms for clarity.

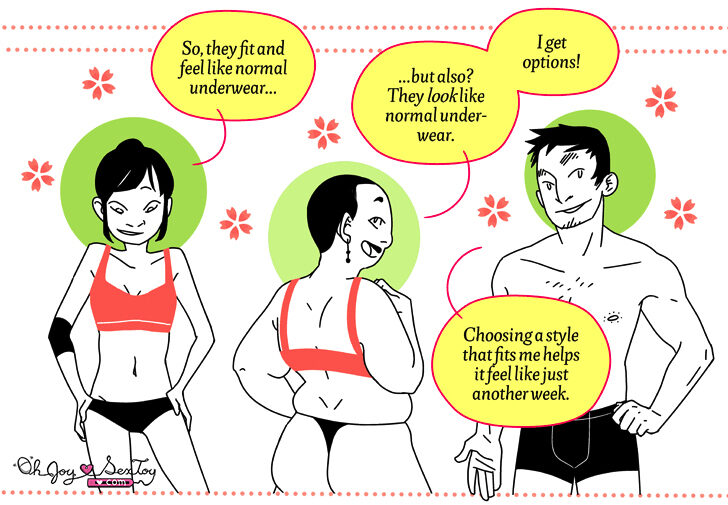

Not only are these comics inclusive in their terminology and audience, but they’re also inclusive in their depictions of characters. Moen has explained that it’s important for her comics to be inclusive of a wide variety of genders and body types because “That’s what the world looks like” (quoted in Anderson-Minshall, 2018). This ethic of inclusivity plays out in her comics and guest comics for OJST. Niki Smith’s (2017) guest comic on period panties (multi-layered underwear meant to catch leaks on heavy menstrual days) features characters wearing those panties and explaining that they look and feel like real underwear and come in a variety of styles. These characters are inclusive of body types and genders: of these three underwear models, one is a man, most likely a transgender man who menstruates (see figure 4). Moen’s own comics show bodies of a variety of races, sizes, genders, and abilities. For example, her comic “How to Suck Cock” features drawings of a variety of bodies asking questions and giving and receiving fellatio. One character is a man in a wheelchair receiving head and saying, “Oh yes, like that, like that” (Moen & Nolan, 2014). These comics are a refreshing turn toward inclusivity, as disability is almost always equated with asexuality, sex education typically constructs sex as able-bodied, and medical discourses often fail to address the sex lives of many with disabilities (Tepper, 2000; Wilkerson, 2002). These comics artists start from the assumption that we should design materials and politics starting with those most marginalized in society, as various queer theorists, disability scholars and activists, and universal design scholars have argued we should (e.g., Dolmage, 2005, 2008; Rose, 2016; Warner, 1999).[3]

These sex-education comics respond to cultural and systemic exclusion of cisgender girls and women and sexual and gender minorities by being radically inclusive of body types, genders, sexual orientations, disability, and sexual desires and pleasures. This feminist and queer positionality often results in a turn to the autobiographical in these comics, which allows for sex-education that explores emotions, ambiguity, and complexity.

Figure 4: Panel from Niki Smith’s (2017) Oh Joy Sex Toy (www.ohjoysextoy.com) guest comic, “Period Panties.” Reproduced with permission.

ALT TEXT: Comic panel featuring three underwear models explaining that period panties look and feel like normal underwear and come in a variety of styles. Two models appear to be cisgender women of different body sizes; one appears to be a transgender man.

Ambiguity and Complexity: The Roles of Autobiography and Emotions in Sex-Education Comics

Many sex-education comics are driven by autobiography rather than simply explaining sexual concepts or practices in a technical, distanced manner. The use of autobiography allows for sex-education comics to incorporate emotions and provide a more complex (and sometimes ambiguous) understanding of sex, sexuality, and gender than traditional sex education. Comics scholars have argued that comics are an ideal medium for displaying ambiguity and complexity, especially in relation to personal experience and emotions. Ian C. M. Williams (2012) suggested that comics are useful for “the discussion of difficult, complex or ambiguous subject matter” (p. 21), especially related to health and medicine, because of the interpretive work necessary to read “a medium of fragments” (p. 22). Nick Sousanis (2015) argued that comics’ multimodality allows for a sort of “refraction” of perspective, helping readers to view the world with more complexity—what he called “unflattening,” or “a simultaneous engagement of multiple vantage points from which to engender new ways of seeing” (p. 32). And because comics are read both synchronically (all at once as we take in the whole page) and diachronically (in sequence, panel to panel) (Eisner, 2008; Squier, 2015), emotions can be depicted as multiple, simultaneous, and contradictory. Jenell Johnson (2018) wrote, “Emotions are usually discussed in isolation from one another, but many comics . . . illustrate their characters experiencing simultaneous, and sometimes contradictory, emotions” (p. 11). For Scott and Fawaz (2018), the ambiguity and multiplicity of comics makes it a “formally queer” medium (p. 202) in that “comics self-consciously multiply and underscore differences at every site of their production so that no single comics panel can ever be made ‘to signify monolithically’” (p. 203, quoting Sedgwick).

Sex-education comics often deploy autobiography in ways that allow for complexity and ambiguity. For instance, Kiku Hughes’s (2015) OJST guest comic, “Ace,” shares her experiences with a lack of libido and learning about asexuality. As Hughes narrates, the commonplace explanations available to her for her lack of libido—like being scared of sex or being “broken”—didn’t help her to understand why she wasn’t interested in sex. However, “Reading about asexuality finally gave a name to my experiences.” Later in the comic, Hughes explores her struggle with coming to terms with this identity category, representing this struggle through a dialogue between two versions of herself.

Hughes’s (2015) difficulty with adopting the identity asexual (which asexual people often shorthand as “Ace,” thus the comics’ title) shows two versions of Hughes struggling with what the identity category means in terms of her lived experience. Through gestural and visual modes in combination with the linguistic mode—Hughes facing away from the reader, then in conversation with herself, pointing in accusation that she masturbates, standing in opposition with clenched fists, looking upward as she shouts with tensed up fingers—Hughes conveys the internal dialogue and helps readers to explore the contradictions about an Ace identity she had to work through. She has to dispel misunderstandings that she has internalized—like that Ace people never get crushes or never masturbate—and she eventually “stopped being so afraid.” Her comic concludes by explaining that being asexual doesn’t equate to loneliness, and in fact, she’s “met amazing, loving people who also identify as Ace” who are quite diverse in their understandings of asexuality. Hughes’s final move in the comic—made possible through the spatial layout, as frames progress from internal dialogue to Hughes contrasting her fears of being alone forever in one panel to a collective of Ace individuals and a text box explaining how she’s met many other Ace people—pulls away from herself as an isolated individual and encourages a collective experience that is diverse and inclusive. Through an intimate personal narrative made possible through the combination of linguistic, visual, gestural, and spatial modes, Hughes’s comic allows for both intimacy and distance, as readers are drawn to her interior world but also see a connection to a broader social world.

Figure 5: Final panels of Kiku Hughes’s (2015) Oh Joy Sex Toy (www.ohjoysextoy.com) comic “Ace,” in which she shares her internal arguments with herself as she attempts to understand asexuality and then finds a community of others who identify as Ace. Reproduced with permission.

ALT TEXT: A series of comics panels in shades of purple in which a young woman argues with herself over understandings of asexuality and then subsequently explains that she’s met others who identify as asexual, who have “taught me to be much kinder to myself.”

This autobiographical and multimodal approach allows for the inclusion of emotions into sex education, features that are too often lacking in school-based and other mainstream sex education (Lenskyj, 1990). For Miller and Bley, it is important to learn from the experiences of others, and they purposefully didn’t make a sex education textbook or manual because those genres often have “a lack of humanized information” (Miller, quoted in “Not Your Mother’s,” 2013).

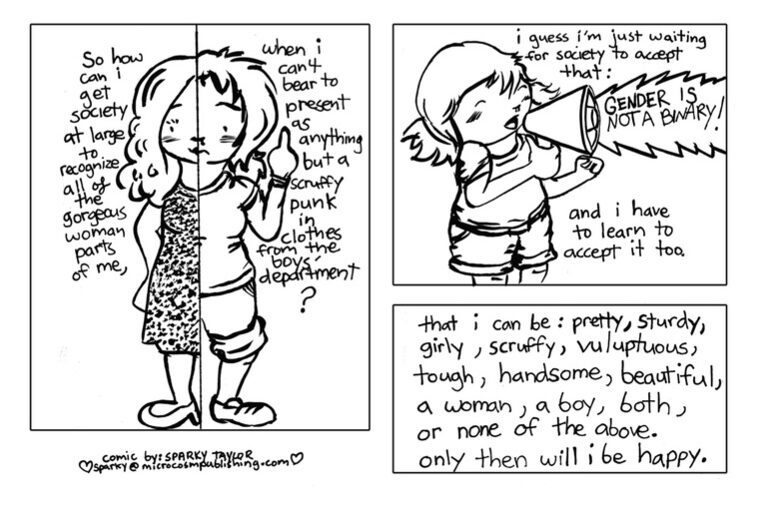

Most of the comics included in Meatloaf work autobiographically and multimodally, allowing for complexity, ambiguity, and even ambivalence. Sparky Taylor’s (2013) two-page “My Body, Myself” shares her experiences with body and gender image as she tries to gain self-acceptance and acceptance from society. This acceptance, though, depends on ambiguity, an acceptance that she can be “pretty, sturdy, girly, scruffy, vuluptuous [sic], tough, handsome, beautiful, a woman, a boy, both, or none of the above,” as she explains in the last panel (p. 48).

Figure 6: Final panels from Sparky Taylor’s (2013) “My Body, Myself” (p. 48). Republished under fair use.

ALT TEXT: Three panels: the first features a short girl split in half, the left half wearing a dress and the right wearing shorts and a t-shirt; the second features the same girl shouting through a bullhorn that GENDER IS NOT A BINARY; the third panel is text explaining that she wants to be accepted for being “pretty, sturdy, girly, scruffy, vuluptuous, tough, handsome, beautiful, a woman, a boy, both, or none of the above.”

Taylor’s comic explores ambiguous and conflicting feelings about gendered and embodied performances, portraying alternative versions of herself. In one panel, she explains that she desires to be seen as feminine sometimes, but she doesn’t like to wear traditional feminine clothes or perfume. This explanation accompanies a drawing of herself wearing a print dress and heals, looking down at her body with a facial expression that might convey disapproval, disappointment, or confusion. The following panels, reproduced in figure 6, express Taylor’s ambivalence by splitting her body in two, representing her conflicting desires to be seen both as a “gorgeous woman” and as a boyish punk (p. 48). Through recognized gendered visual elements (heels and a dress versus sneakers, shorts, and a t-shirt) and gestures (the raising of a middle finger), Taylor presents an internal conflict and then depicts an integrated version of herself that allows for ambiguous gender performance and identity as she shouts “GENDER IS NOT A BINARY” through a bullhorn. Taylor’s comic thus explores ambivalence and ambiguity of gender expression through a multimodal comic in which linguistic explanations, gestures, visuals, and spatial progression of her internalized experiences (visualized and externalized through her bodily representations) work in conjunction with each other.

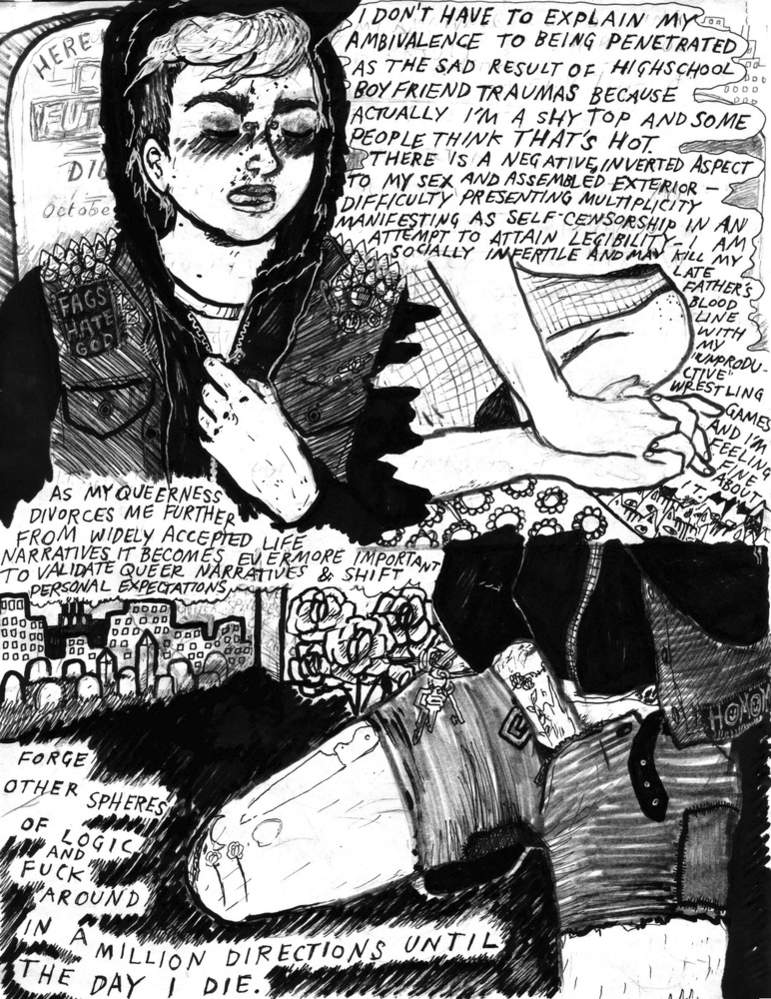

Likewise, Katrina’s (2013) two-page untitled comic in Meatloaf explores complexity around being queer through a multimodal personal narrative. The first page of her comic provides a drawing of a person passed out in a bed in a messy room accompanied by text:

The second page features a spatial collage of drawings: a self-portrait, a gravestone, hand-holding, masturbation with clothes on, flowers, and a cityscape. The gravestone, partially hidden by the portrait, appears to read, “HERE LIES THE FUTURE.” Text wrapping around the drawings explains that because Katrina is a “shy top,” she doesn’t have to explain “her ambivalence to being penetrated” to others—an ambivalence that’s the result of sexual trauma from high school (p. 165). Katrina explains that “There is a negative, inverted aspect to my sex and assembled exterior—difficulty presenting multiplicity” (p. 165). Katrina’s queerness is anti-social: she calls herself “socially infertile” and the potential murderer of her “father’s blood line” (p. 165). She concludes, “As my queerness divorces me further from widely accepted life narratives, it becomes even more important to validate queer narratives & shift personal expectations” (p. 165).

Katrina’s (2013) comic, like Taylor’s, doesn’t teach didactically, but rather provides an ambivalent and complex experience of being queer in the world. These comics teach that bodies are complex and messy, deploying multiple modes to convey this message. Chute (2010) has explained that comics is “a procedure . . . of embodiment” (p. 193) in which subjectivity is inscribed on the page as “Handwriting underscores the subjective positionality of the author” (p. 11). Through the intimacy of reading Katrina’s handwriting (a visual and linguistic explanation of her abject subject position) and experiencing the visual and gestural representations of her embodiment—in bed, or later in a punk jacket, or holding hands, or masturbating with her shorts on, spatially juxtaposed against each other—readers gain a sense of the complexity of queer embodied experiences. The multimodal rhetoric of Katrina’s comic further works to bring the past (linguistically through her handwritten narration about boyfriend trauma), present (visually through her self-portrait), and future (the visual gravestone and linguistic explanation of her social infertility) together in one visual-spatial space, which consequently integrates trauma into understandings of queerness, embodiment, and sexuality—understandings that allow for complexity, validation, and exploration of identities that can “fuck around in a million directions” (Katrina, 2013, p. 165). (On the possibilities of comics to queer temporality, especially in regard to trauma, in ways that create complexity for identities, see Chute, 2017; Cvetkovich, 2008; Wanzo, 2018).

Figure 7: The second page of Katrina’s (2013) two-page untitled comic exploring her queer identity and sexuality (p. 165). Republished under fair use.

ALT TEXT: A collage of images like a self-portrait, a gravestone, hand-holding, flowers, a cityscape, and masturbation with clothes on, accompanied by text that wraps around the images.

Through personal, multimodal, autobiographical accounts that incorporate relational, emotional, and contextual aspects of sex and sexuality, these comics allow for a more complex and thorough sex-education experience for readers that incorporates desires, pleasures, identities, and situated contexts.

Instructions and Technical Information

In addition to exploring sex and gender through autobiography, sex-education comics also present easy-to-follow, though still complex, instructional and technical information regarding sex. In Comics and Sequential Art, Will Eisner (2008) explained that comics are an ideal medium for conveying procedures or processes because of comics’ sequential nature. More recently, Han Yu (2016) has argued that comics can be a productive medium for technical communication, including relaying educational and instructional material.

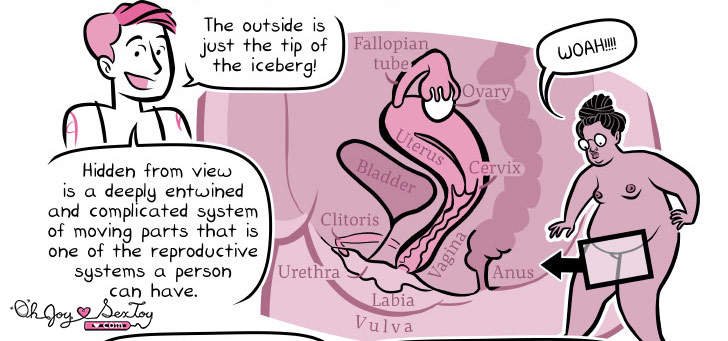

Sex-education comics typically provide technical information in one of two approaches: either technical illustrations and explanations of body parts and processes, or instructional material that explains a process. The first is quite frequent, as many sex-education comics provide annotated diagrams of sexual anatomy. Chute (2017) has observed that comics lend themselves to the diagrammatic, allowing for the “display [of] otherwise hard-to-represent realities and sensations” (p. 241) because of the affordances of drawings for showing both interiority and exteriority simultaneously. For example, Moen’s illustrations in “Vulvovaginal Anatomy” on OJST (Moen & Nolan, 2018c) display detailed drawings and diagrams of both external and internal female sexual organs. In figure 8 below, Moen provides a cross-section diagram of female anatomy, allowing for annotations of both interior and exterior organs. As a sort of peer teacher—a frequent strategy in instructional comics (Yu, 2016)—Moen explains to another character (and the readers) that “The outside is just the tip of the iceberg.” The rest of the comic proceeds to provide a “quick tour” of the vulvovaginal system as Moen traverses interior organs and explains the functions and of these organs and how they work.

Figure 8: Panel from “Vulvovaginal Anatomy” (Moen & Nolan, 2018c) on Oh Joy Sex Toy (www.ohjoysextoy.com). Reproduced with permission.

ALT TEXT: A diagram of vulvovaginal sexual organs with labels as Moen’s character explains that “Hidden from view is a deeply entwined and complicated system of moving parts that is one of the reproductive systems a person can have.”

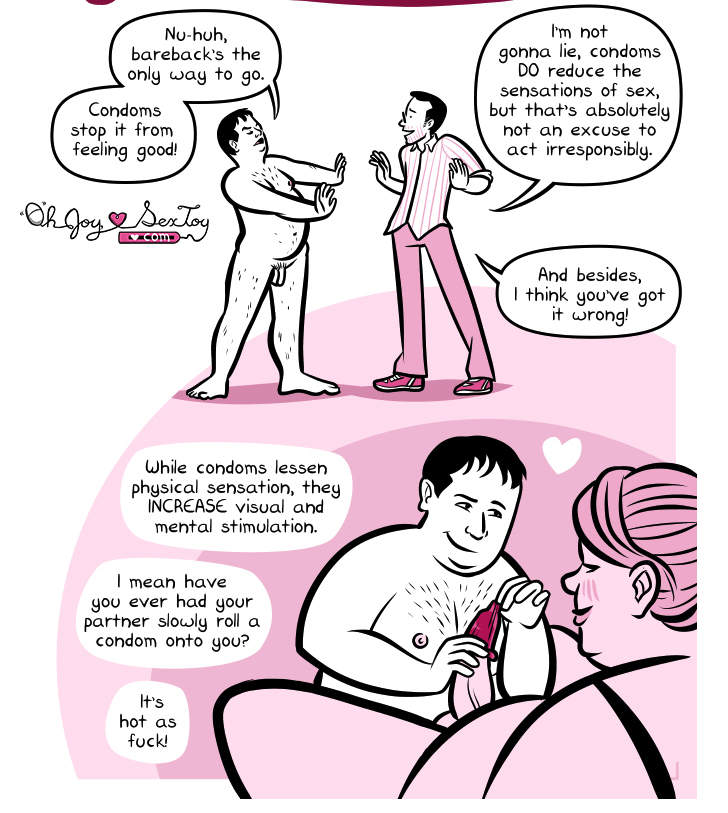

But these technical comics are not solely technical; they are also attitudinal in nature. As both Eisner (2008) and Yu (2016) have shown, instructional comics can also be attitudinal instructions: they shape expectations, beliefs, values, and attitudes towards processes or procedures. Instructional comics often don’t simply explain how to do something, like put on a condom; they also shape attitudes toward the topic through the combination of multiple modes.

For instance, in the tradition of Safer Sex Comix, these comics also eroticize condom usage. OJST’s “Condom Basics” (Moen & Nolan, 2015) eroticizes condoms in multiple ways, drawing on the combination of multiple modes in order to do so. First, it opens with Nolan explaining how at the age of 14 he snuck out of a movie to purchase a condom in the theatre bathroom’s condom machine. The comic begins with a single frame in which Nolan holds up a comic and begins narrating and then proceeds spatially through a series of frames in which Nolan is depicted as a character sneaking out of the movie in search of the condom machine. Text above each panel narrates his adventure, as he explains that he didn’t have intentions of having sex soon, but “HAVING a condom, becoming PREPARED, brought me one step closer to actual sex.” So, first, condoms are erotic objects before one ever has sex because they make sex a potential actuality. Second, as Nolan explains in subsequent panels, returning visually and gesturally as a narrator and peer teacher, condoms are “little reminders of the future sex you’re going to have. And that makes them sexy.” And third, in response to another character objecting that condoms decrease sensation, Nolan argues that “they INCREASE visual and mental stimulation.” The act of having a condom rolled on, Nolan suggests, is “hot as fuck!” Through the combination of linguistic explanation and narration in speech bubbles; visual diagrams and examples; spatial movements between Nolan as a character, Nolan as a peer teacher, diagrams, and example of condom use (as in figure 9); and gestural modes (including the second character’s resistant stance and the act of putting on a condom), “Condom Basics” works to provide technical information while also providing an attitudinal, multimodal argument.

Figure 9: Panels from “Condom Basics” (Moen & Nolan, 2015) on Oh Joy Sex Toy (www.ohjoysextoy.com) explaining that condoms can “INCREASE visual and mental stimulation.” Reproduced with permission.

ALT TEXT: Top: Drawing of a man saying that condoms desensitize, while another man responds that that’s “not an excuse to act irresponsibly”; Bottom: Dialogue bubbles explain that condoms “INCREASE visual and mental stimulation,” accompanied by a drawing of someone putting a condom on someone else.

Sex-education comics, then, provide technical explanations and instructions while shaping the attitudes of readers toward those practices: They eroticize and make accessible complex human anatomy and practices like condom usage, birth control methods, safer sex practices, and more.

Conclusion: Toward a Sexual Techné

Sex-education comics, by personalizing sex education through autobiography and by sharing technical information that shapes attitudes, help to develop their readers’ sexual literacy and agency. And by taking feminist and queer positionalities, sex-education comics re-orient readers to their bodies and to society, a re-orientation that challenges and critiques norms and “probe[s] the intermingling of sex and power” (Alexander & Rhodes, 2012, p. 202). This sexual literacy and agency becomes a sort of techné, a contextual practice that is both individual (related to identity and one’s own sexual interests and desires) and shared. The sexual literacy and agency encouraged by these comics is ultimately a civic one. Jonathan Alexander and Jacqueline Rhodes (2012) have described techné as “a sort of generative lived knowledge,” a view of techné “that points less to the prescribed how-to sense of the term and more to the ethical, civic dimension” (Alexander & Rhodes, 2012, pp. 211–212). Unlike traditional sex education, which can focus on avoiding risks and makes sex and reproduction mechanical, these sex-education comics have a civic component.

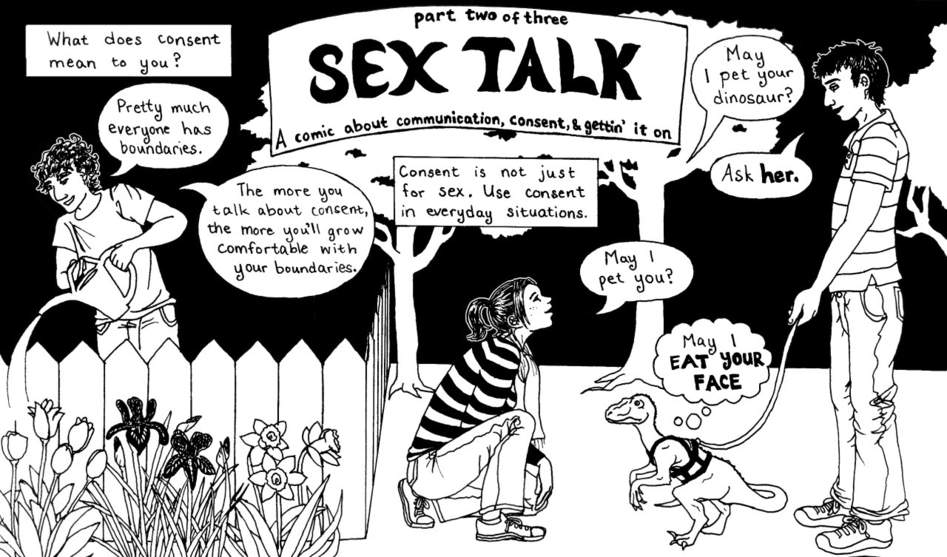

One last comic to exemplify this point: Maisha Foster-O’Neal’s (2010/2015) “Sex Talk” (which was also printed in Miller and Bley’s 2013 Meatloaf). “Sex Talk” is a three-page explanation of consent that incorporates discussions of boundaries and pleasures. Consent is a frequent topic for sex-education comics, and importantly so. Moen has argued that consent has not been adequately taught in school-based sex education, and that consent is intimately tied to pleasure: “pleasure is not taught. It’s not explicitly said. Another huge problem, is if you aren’t teaching about pleasure, then you’re not teaching about consent either” (quoted in Zaloker, 2014). And further, given a culture that doesn’t adequately teach about consent and respecting bodily integrity and boundaries, it’s necessary to continue to teach consent as an ethical, relational practice. Kathleen Ann Livingston (2015) has argued that consent education is community-based, arising out of feminist and queer spaces, and that we should understand consent as a “rhetorical process by which we learn to play carefully with power and each other, to articulate our boundaries and desires and ask for what we need” (p. 18). Thus, consent is a set of ethical practices, not simply a matter of risk and danger, but also of pleasure and boundaries. Further, as many sex-education comics argue, consent is not solely tied to sex: it is an ethical practice, a techné, for being in relation with others. Comics that teach sex education and consent become “alternative” sites of extra-curricular rhetorical education (Cavallaro, 2015; Gere, 1994), teaching readers to effectively communicate about needs, pleasures, boundaries, and desires.

Figure 10: Part one of Maisha Foster-O’Neal’s (2010/2015) “Sex Talk.” Reproduced under Creative Commons.

ALT TEXT: A page of comics showing a variety of characters exemplifying that “Consent is when you discuss and respect boundaries” and “an enthusiastic yes means yes”; bottom panels provide advice about sharing what one likes and dislikes, sharing risk factors, and asking permission.

As do other comics (like Rotman’s 2016b You’re So Sexy and 2016a Not on My Watch), Foster-O’Neal’s (2010/2015) “Sex Talk” explains that “Consent is when you discuss and respect boundaries” (part 1). It involves conversation with others about your pleasures, dislikes, risk factors, and boundaries. As Foster-O’Neal’s comic explains, consent is an ethic for “everyday situations” (part 2). In a light-hearted example, Foster-O’Neal shows a young woman asking someone, “May I pet your dinosaur.” He responds, “Ask her,” which she does, and the dinosaur thinks in the ethic of consent being exhibited: “May I EAT YOUR FACE” (part 2).

Figure 11: The first panel in part two of Foster-O’Neal’s (2010/2015) “Sex Talk.” Reproduced under Creative Commons.

ALT TEXT: A full-width panel featuring a young woman asking “May I pet your dinosaur?” to a man, who responds, “Ask her”; she subsequently asks a small dinosaur, held on a leash, and it responds by thinking, “May I EAT YOUR FACE.”

The sort of techné taught by “Sex Talk” and other sex-education comics is a relational and embodied practice—an ethic of both self and relationality. That is, it is not reducible to simply skill or technical knowledge, but is rather generative of new relationships and ways of being in the world. Such a view of sexual techné, then, combats shame and ignorance as well—not by denying shame and replacing it with pride—but by admitting shame and ignorance and learning new ways to experience pleasure with our bodies. Michel Foucault (1997) has famously argued that what was radical or disturbing about homosexuality was not two men having sex—it was men finding new ways to be intimate. That is, what makes nonnormative sexuality radical is that it affords the possibility of new ways of relating to each other. Sex and sexuality, then, become sites of invention, a techné that is, as Alexander and Rhodes (2012) put it, “generative” (p. 211). Sex-education comics teach sexuality as a generative practice through their multimodal rhetorics, opening the possibility for readers to explore how sexuality is related to their identities, how they can create new and different relationships, how they can understand their own bodies differently, how sex and sexuality is a “knowledge complex” (Alexander, 2008, p. 12) that is, indeed, complex, involving not solely sexual behaviors but also identities and social relations.

It is worth noting that Foster-O’Neal created her comic for her Gender in Relational Communication course at Lewis & Clark University. She persuaded her professor to allow her to research consent and create a comic rather than a traditional 15-page paper, and when she finished, she posted the comic all over campus and then co-facilitated a workshop on consent and sex (“Student Pens,” 2010). Rhetoric and composition scholars have persuasively argued that comics can and should be sites of multimodal composition in our writing courses (Jacobs, 2014, 2015; F. Johnson, 2014; Wierszewski, 2014). In closing, I want to join these calls by suggesting that comics—grassroots and amateur—are important sites for analysis in our classes and for student production that responds to real-world exigencies. Not that these comics studied and created by students need to be sex-education comics (though they can be!). But comics are important sites of civic education and engagement that, through their ability to present information in a variety of modes and engage readers, can address real civic problems in communities, on our campuses, and in our world.

Acknowledgments

I wish to acknowledge that this article was written and revised within the historical territories of the Teya, Jumano, Apache, and Comanche peoples. Thank you to Dale Jacobs for feedback on an earlier draft of this manuscript and to Matthew Nolan, Erika Moen, Niki Smith (http://niki-smith.com/), and Kiku Hughes for permission to include comics from Oh Joy Sex Toy.

References

Abate, M. A., Grice, K. M., & Stamper, C. N. (Eds.). Lesbian content and queer female characters in comics [Special issue]. Journal of Lesbian Studies, 22(4).

Alcoff, L. (1988). Cultural feminism versus post-structuralism: The identity crisis in feminist theory. Signs, 13(3), 405–436. doi:10.1086/494426

Alexander, J. (2008). Literacy, sexuality, pedagogy: Theory and practice for composition studies. Logan, UT: Utah State University Press.

Alexander, J, & Rhodes, J. (2012). Queerness, multimodality, and the possibilities of re/orientation. In K. L. Arola & A. F. Wysocki (Eds.), Composing(media) = composing(embodiment): Bodies, technologies, writing, the teaching of writing (pp. 188–212). Logan, UT: Utah State University Press.

Allen, L. (2007). Denying the sexual subject: Schools’ regulation of student sexuality. British Educational Research Journal, 33(2), 221–234. doi:10.1080/01411920701208282

Anderson-Minshall, J. (2018, May 30). Sex ed you won’t get in school. Advocate. Retrieved from https://www.advocate.com/current-issue/2018/5/30/sex-ed-you-wont-get-school

Bay-Cheng, L. Y. (2003). The trouble of teen sex: The construction of adolescent sexuality through school-based sexuality education. Sex Education: Sexuality, Society, and Learning, 3(1), 61–74. doi:10.1080/1468181032000052162

Boyle, C., & Rivers, N. A. (2016). A version of access. Technical Communication Quarterly, 25(1), 29–47. doi:10.1080/10572252.2016.1113702

Cavallaro, A. J. (2015). Fighting biblical “textual harassment”: Queer rhetorical pedagogies in the extracurriculum. Enculturation: A Journal of Rhetoric, Writing, and Culture, 18. Retrieved from http://enculturation.net/fighting-biblical-textual-harassment

Chute, H. (2010). Graphic women: Life narrative and contemporary comics. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

Chute, H. (2017). Why comics? From underground to everywhere. New York, NY: HarperCollins.\Crimp, D. (1987). How to have promiscuity in an epidemic. October, 43, 237–271.

Cvetkovich, A. (2008). Drawing the archive in Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home. Women’s Studies Quarterly, 36(1–2), 111–128.

Czerwiec, MK. (2013, August 28). Not your mother’s meatloaf interview [Blog post]. Graphic Medicine. Retrieved from https://www.graphicmedicine.org/not-your-mothers-meatloaf-interview/

Dolmage, J. (2005). Disability studies pedagogy, usability and universal design. Disability Studies Quarterly, 25(4). Retrieved from http://dsq-sds.org/article/view/627/804

Dolmage, J. (2008). Mapping composition: Inviting disability in the front door. In C. Lewiecki-Wilson & B. J. Brueggemann (Eds.), Disability and the teaching of writing: A critical sourcebook (pp. 14–27). Boston, MA: Bedford/St. Martin's.

Eisner, W. (2008). Comics and sequential art: Principles and practices from the legendary cartoonist (Revised ed.). New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company.

Elbaz, G. (1998). Social movements as health-educators. Journal of Health Education, 29(5), 295–303. doi:10.1080/10556699.1998.10603355

Estren, M. J. (2012). A history of underground comics (20th anniversary ed.). Oakland, CA: Ronin Publishing.

Farmer, J., & Chevli, L. (2018). Abortion Eve. In J. Johnson (Ed.), Graphic reproduction: A comics anthology (pp. 19–53). University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press. (Original work published 1973)

Foucault, M. (1997). Friendship as a way of life (John Johnson, Trans.). In P. Rabinow (Ed.), Ethics: Subjectivity and truth (pp. 135–140). New York, NY: The New Press.

Fountain, L (Ed.). (1972). Incredible facts o’ life: Sex education funnies. San Francisco, CA: Multi Media Resource Center.

Foster-O’Neal, M. (2015). Sex talk [Comic]. Retrieved from http://maishaparadox.tumblr.com/post/120165245764 (Original work published 2010)

Gere, A. R. (1994). Kitchen tables and rented rooms: The extracurriculum of composition. College Composition and Communication, 45(1), 75–92.

Grover, J. (1988). Safer sex guidelines and bibliography. Jump Cut: A Review of Contemporary Media, 33, 118–123. Retrieved from https://www.ejumpcut.org/archive/onlinessays/JC33folder/SaferSextips-biblio.html

Grover, J. Z. (1995). Visible lesions: Images of the PWA. In C. K. Creekmur & A. Doty (Eds.), Out in culture: Gay, lesbian, and queer essays on popular culture (pp. 354–381). Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Hall, J. (Ed.). (2012). No straight lines: Four decades of queer comics. Seattle, WA: Fantagraphics Books.

Hatfield, C. (2005). Alternative comics: An emerging literature. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi.

Hughes, K. (2015, December 22). Ace by Kiko H [Webcomic]. Oh Joy Sex Toy. Retrieved from https://www.ohjoysextoy.com/ace-kiku-h/

Jacobs, D. (2013). Graphic encounters: Comics and the sponsorship of multimodal literacy. New York, NY: Bloomsbury.

Jacobs, D. (2014). “There are no rules. And here they are”: Scott McCloud’s Making comics as a multimodal rhetoric. Journal of Teaching Writing, 29(1), 1–20.

Jacobs, D. (Ed.). (2015). Comics, multimodality, and composition [Special issue]. Composition Studies, 43(1).

Johnson, F. (2014). Perspicuous objects: Reading comics and writing instruction. Kairos: A Journal of Rhetoric, Technology, and Pedagogy, 19(1). Retrieved from http://technorhetoric.net/19.1/topoi/johnson/index.html

Johnson, J. (Ed.). (2018). Graphic reproduction: A comics anthology. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press.

Katrina. (2013). Untitled. In S. Miller & L. Bley (Eds.), Not your mother’s meatloaf: A sex education comic book (pp. 164–165). Berkeley, CA: Soft Skull Press.

Lenskyj, H. (1990). Beyond plumbing and prevention: Feminist approaches to sex education. Gender and Education, 2(2), 217–230. doi:10.1080/0954025900020206

Livingston, K. A. (2015). The queer art & rhetoric of consent: Theories, practices, pedagogies (Doctoral dissertation). Michigan State University, East Lansing. Retrieved from https://d.lib.msu.edu/etd/3645

Lopes, P. (2009). Demanding respect: The evolution of the American comic book. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

McAllister, M. P. (1992). Comic books and AIDS. Journal of Popular Culture, 26(2), 1–24.

McGurk, C. (2018). Lovers, enemies, and friends: The complex and coded early history of lesbian comic strip characters. Journal of Lesbian Studies, 22(4), 336–353. doi:10.1080/10894160.2018.1449502

Miller, S., & Bley, L. (Eds.). (2013). Not your mother’s meatloaf: A sex education comic book. Berkeley, CA: Soft Skull Press.

Moen, E. (2005). Girlfuck: An introduction to girl-on-girl lovin’. QZAP Zine Archive. Retrieved from http://archive.qzap.org/index.php/Detail/Object/Show/object_id/169

Moen, E., & Nolan, M. (2014, June 3). How to suck cock [Webcomic]. Oh Joy Sex Toy. Retrieved from https://www.ohjoysextoy.com/blowjobs/

Moen, E., & Nolan, M. (2015, January 6). Condom basics [Webcomic]. Oh Joy Sex Toy. Retrieved from https://www.ohjoysextoy.com/condombasics/

Moen, E., & Nolan, M. (2016–2017). Oh joy sex toy (4 vols.) [E-book]. Portland, OR: Erika Moen Comics & Illustration & Limerence Press. Retrieved from https://www.ohjoysextoy.com/ebooks-shop/

Moen, E., & Nolan, M. (2018a). Drawn to sex: The basics. Portland, OR: Erika Moen Comics & Illustration & Limerence Press.

Moen, E., & Nolan, M. (2018b, May 1). Drawn to sex Kickstarter & fund drive [Webcomic]. Oh Joy Sex Toy. Retrieved from https://www.ohjoysextoy.com/drawn-to-sex-kickstarter-n-fund-drive/

Moen, E., & Nolan, M. (2018c, July 10). Vulvovaginal anatomy [Web comic]. Oh Joy Sex Toy. Retrieved from https://www.ohjoysextoy.com/vulvovaginal/

Mulvey, L. (1999). Visual pleasure and narrative cinema. In L. Braudy & M. Cohen (Eds.), Film theory and criticism: Introductory readings (pp. 833–844). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. (Original work published 1975)

New London Group. (1996). A pedagogy of multiliteracies: Designing social futures. Harvard Educational Review, 66(1), 60–92. doi:10.17763/haer.66.1.17370n67v22j160u

Not your mother’s meatloaf. (2012). Retrieved from https://web.archive.org/web/20121211033423/http://sexedcomicproject.blogspot.com/

“Not your mother’s meatloaf” by S. Miller and L. Bley teaches sex education using comics. (2013, August 5). Huffington Post. Retrieved from https://www.huffingtonpost.com/2013/08/05/not-your-mothers-meatloaf_n_3690666.html

Nyberg, A. K. (1998). Seal of approval: The history of the Comics Code. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi.

Patton, C. (1987). Resistance and the erotic: Reclaiming history, setting strategy as we face AIDS. Radical America, 20(6), 68–78. Brown Digital Repository. Brown University Library. Retrieved from https://repository.library.brown.edu/studio/item/bdr:89292/

Patton, C., & Kelly, J. (1987). Making it: A woman’s guide to sex in the age of AIDS. Ithaca, NY: Firebrand Books. Barnard Center for Research on Women. Feminism and Sexual Health. Retrieved from http://bcrw.barnard.edu/archive/sexualhealth.htm

Pilcher, T. (2008). Erotic comics: A graphic history (vol. 1) [Kindle edition]. Retrieved from Amazon.com.

RAD Remedy & Rotman, I. (2016a). Dr. RAD’s queer health show: Read this first! Introduction to terms and disclaimer. RAD Remedy. Retrieved from http://zines.radremedy.org/

RAD Remedy & Rotman, I. (2016b). Dr. RAD’s queer health show: Issue one: Self exams and check ups. RAD Remedy. Retrieved from http://zines.radremedy.org/

Robbins, T. (1999). From girls to grrrlz: A history of women’s comics from teens to zines. San Francisco, CA: Chronicle Books.

Robbins, T. (2013). Pretty in ink: North American women cartoonists 1896–2013. Seattle, WA: Fantagraphics Books.

Rose, E. J. (2016). Design as advocacy: Using a human-centered approach to investigate the needs of vulnerable populations. Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, 46(4), 427–445. doi:10.1177/0047281616653494

Rotman, I. (2016a). Not on my watch: A bystander’s handbook for the prevention of sexual violence (2nd ed.) [E-book]. Retrieved from https://isabella-rotman.squarespace.com/not-on-my-watch/

Rotman, I. (2016b). You’re so sexy when you aren’t transmitting STI’s (2nd ed.). Michigan: Isabella Rotman.

Safer sex comix [Comic book image]. (1986). Gay Men’s Health Crisis. Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. Retrieved from http://cprhw.tt/o/2Dztr/

Sánchez, R. (2006). On a critical realist theory of identity. In L. M. Alcoff, M. Hames-García, S. P. Mohanty, & P. M. L. Moya (Eds.), Identity politics reconsidered (pp. 31–52). New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

Scott, D., & Fawaz, R. (2018). Introduction: Queer about comics. American Literature, 90(2), 197–219. doi:10.1215/00029831-4564274

Smith, N. (2017, October 10). Period panties by Niki Smith [Webcomic]. Oh Joy Sex Toy. Retrieved from https://www.ohjoysextoy.com/period-panties/

Sousanis, N. (2015). Unflattening. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Squier, S. M. (2014). Comics in the health humanities. In T. Jones, D. Wear, & L. D. Friedman (Eds.), Health humanities reader (pp. 226–241). New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Squier, S. M. (2015). The uses of graphic medicine for engaged scholarship. In MK Czerwiec, I. Williams, S. M. Squier, M. J. Green, K. R. Myers, & S. T. Smith (Eds.), Graphic medicine manifesto (pp. 41–66). University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press.

Student pens comics to encourage better communication about sex. (2010, December 21). Newsroom—Lewis & Clark. Retrieved from http://www.lclark.edu/live/news/9512-student-pens-comics-to-encourage-better-communication-about-sex

Taylor, S. (2013). My body, myself. In S. Miller & L. Bley (Eds.), Not your mother’s meatloaf: A sex education comic book (pp. 47–48). Berkeley, CA: Soft Skull Press.

Tepper, M. S. (2000). Sexuality and disability: The missing discourse of pleasure. Sexuality and Disability, 18(4), 283–290. doi:10.1023/A:1005698311392

Tilley, C. L. (2012). Seducing the innocent: Fredric Wertham and the falsifications that helped condemn comics. Information & Culture: A Journal of History, 47(4), 383–413. doi:10.1353/lac.2012.0024

Tilley, C. L. (2018). A regressive formula of perversity: Wertham and the women of comics. Journal of Lesbian Studies, 22(4), 354–372. doi:10.1080/10894160.2018.1450001

Warner, M. (1999). The trouble with normal: Sex, politics, and the ethics of queer life. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Wanzo, R. (2018). The normative broken: Melinda Gebbie, feminist commix, and child sexuality temporalities. American Literature, 90(2), 347–375. doi:10.1215/00029831-4564334

Wertham, F. (1954). Seduction of the innocent. New York, NY: Rinehart & Company.

Wierszewski, E. A. (2014). Creating graphic nonfiction in the postsecondary English classroom to develop multimodal literacies. ImageTexT: Interdisciplinary Comics Studies, 7(3). Retrieved from http://www.english.ufl.edu/imagetext/archives/v7_3/wierszewski/

Wilkerson, A. (2002). Disability, sex radicalism, and political agency. NWSA Journal, 14(3), 33–57.

Williams, I. C. M. (2012). Graphic medicine: Comics as medical narrative. Medical Humanities, 38(1), 21–27. doi:10.1136/medhum-2011-010093

Yu, H. (2016). The other kind of funnies: Comics in technical communication [E-book]. Baywood. ProQuest eBook Central.

Zaloker, S. (2014, September 18). Drawn to sex: Erika Moen lays it all out on the story board in the sex-positive world of comics. Street Roots News. Retrieved July 21, 2018, from http://news.streetroots.org/2014/09/18/drawn-sex-erika-moen-lays-it-all-out-story-board-sex-positive-world-comics

[1] Readers interested in fuller histories of comics might consult the following: Hatfield (2005) on alternative comics and graphic novels; Estren (2012) on underground comix; Jacobs (2013) on comics as sponsors of literacy; Lopes (2009) on American comic books; Chute (2010b) and Robbins (1999, 2013) on women and girls in comics; Pilcher (2008) on erotic comics; and Hall (2012) on queer comics. For more on queer and lesbian perspectives on comics, see recent special issues of the Journal of Lesbian Studies (Abate, Grice, & Stamper, 2018) and American Literature (Scott & Fawaz, 2018).

[2] For a rich discussion of the Comics Code, see Nyberg (1998); on moral panics about comics, see Jacobs (2013); see Tilley (2012) for a discussion of “how Wertham manipulated, overstated, compromised, and fabricated evidence” for Seduction of the Innocent (p. 386) and Tilley (2018) for an analysis of how Wertham viewed strong women comic book characters like Wonder Woman as non-normative, deviant, and intricately tied to violence.

[3] While these comics are often radically inclusive, due to their visual nature they are often not accessible to blind and low-vision readers. Most webcomics artists don’t provide alternative ways to access their comics, like descriptions and transcripts. Casey Boyle and Nathaniel A. Rivers (2016) have argued that designing for accessibility involves the creation of multiple versions of a composition. Accessibility in this view means “offer[ing] different versions that operate according to their own specific medial logics” (p. 31). Many webcomics could be more accessible through providing a different, text-based version for blind and low-vision readers.