Thanks, I Made It: Handmade Clothing as an Embodied Rhetoric of Possibility

Anna Hensley, University of Cincinnati

[Craft] is a training camp for empowered autonomy. It is fearlessness toward the decrees of consumerism and peer pressure and, in its most expressive form, the violence of fashion. Craft can be a tool for overcoming fear. It is a way to be free.

—Otto von Busch (2014), “Crafting Resistance”

For most people in the United States, making their own clothes through any combination of knitting, crocheting, weaving, or sewing is very much a niche hobby—something pursued less out of necessity or economy and more out of a desire to create and connect with other makers. But with the revived interest in traditional crafts holding strong since the early 2000s, more people have the means and the desire to handcraft garments that are made to measure and designed to reflect personal style, personal values, and diverse identities. Makers are increasingly recognizing the value of craft as a way to throw off the restrictive, normative identity options made available in stores and instead present to the world a bespoke version of the self. As Jessica Bain (2016) notes in her article analyzing the writing of contemporary sewing bloggers, many sewists enjoy their craft in no small part because it “offer[s] a way of transcending fashion and gender norms” (p. 64).

Other researchers have situated the craft revival as a response to the disjointing pressures that emerge, particularly in professional life, as a result of late capitalism (Jack Z. Bratich and Heidi M. Brush, 2011; Maureen Daly Goggin, 2015). In a recent Washington Post article, immigration attorney Sumaiya Ahmed (2019) described how she turned to sewing—a craft she had grown up watching her mother and other women in her family engage in on a near-daily basis—to help her deal with the debilitating internal conflict, anxiety, and depression she experienced as she struggled to square the intense pressures of her nascent law career with her own sense of identity. Crediting the creative process of sewing with steering her away from corporate law firms that offered little space for the expression of her creativity and putting her on the path to fulfilling non-profit work, Ahmed wrote, “I have accessed a craft that reminds me of my capacity for trial and error. As I checked off projects, sewing confirmed that if I tackle something a little bit each day, I can progress toward my goal. In a way, my sewing practice offered an analogue to moving forward in my career.”

This essay explores garment making as one way to respond to the restrictive pressures of normative dress practices and the institutional pressures they often represent. Like Ahmed, my craft practice has grown alongside my academic career, the two becoming increasingly enmeshed as I moved from undergraduate to graduate student to junior professor. The process of sewing and knitting my own clothes has allowed me to carve out a professional identity in a field where, at times, my body and my identity have not seemed to easily fit. Drawing on material rhetorics of craft, I theorize my personal experience as a fat, queer woman who began to sew and knit my own clothing as a response to both significantly limited professional dress options and the overwhelming pressure I felt as a Ph.D. candidate in a competitive program. Responding to the call from Maureen Johnson, Daisy Levy, Katie Manthey, and Maria Novotny (2015) to consider “how our bodies inform our ways of knowing,” I reflect on how the tactile process of creating and then wearing bespoke garments helped me see new possibilities for myself as an emerging professional.

By theorizing my own experience as an academic and maker, I hope to demonstrate that the rhetorical power of self-stitched clothing extends beyond the material object. While the message signified through the unique, slowly produced, and often imperfect handmade garment is certainly important, the process of craft and the embodied experience of wearing handmade garments can have equally transformative effects for the maker. As Otto von Busch argued in “Crafting Resistance” (2014), craft as a process can help us cultivate fearlessness in the face of limits by allowing us to draw on the histories that precede us and the communities that support us as we create and embody new possibilities. Ultimately, I argue that wearing handmade clothes in the workplace is an embodied rhetoric of possibility that sends a powerful message to ourselves and to our colleagues, clients, and students about our collective power to critically transform the spaces where we live and work.

The Material Rhetoric and Transformative Power of Craft

Understanding the embodied rhetoric of handmade clothes builds on feminist work that asks us to consider how the rhetorical power of the material extends beyond the way that the object is read and interpreted. Rather than treating the material as inert and passive, feminist scholars of material rhetorics call for critical attention to the way that material forms and processes of material production function as sites of rhetorical agency where meaning is negotiated. For instance, in their work on embodiment, Johnson et al (2015) build on the move away from understanding the body within the subject/object binary and instead urge scholars to “experience the body as an entity with its own rhetorical agency” and to seriously consider how “our bodies inform our ways of knowing” (p. 39).

Work on the material rhetorics of craft has likewise argued that the rhetoricity of traditional craft exceeds the interpretation of the object produced. In her study of the practices of the Gee’s Bend quiltmakers, Vanessa Kraemer Sohan (2015) argues that “women’s quiltmaking practices blur the lines between the verbal and the visual,” such that the quilters in her study “demonstrate[d] the power of the needle as pen” (p. 296). In Sohan’s analysis, quiltmaking is significant not just because of the production of artifacts that signify the culture, identity, and context of the makers, but because the aesthetic and material process of creating the quilt is itself an epistemic, discursive process that shapes and influences the identities of the makers and the larger community in which they situate themselves. In the introduction to Women and the Material Culture of Needlework and Textiles, 1750-1950, Maureen Goggin Daly (2009) similarly argues for an understanding of traditional needlecrafts as an important site of discursive meaning making for many women in history, despite the fact that these activities have often been overlooked or uncritically dismissed.

Feminist scholars have built on this understanding of craft as discursive work in order to better understand how women use craft as a means to negotiate meaning and as an entry point into larger conversations. Challenging the vision of traditional craft as the work of women relegated to the depoliticized private sphere, Heather Pritash, Inez Schaechterle, and Sue Carter Wood (2009) instead contend that needlework has traditionally functioned as a “vehicle through which women have constructed discourses of their own, ones offering a broader range of positions from which to engage dominant culture” (p. 27). Of course, the meaning of traditional craft is not static. While needlework may have historically allowed women a broader means of engaging the dominant culture, women’s relationship with craft as a form of cultural engagement necessarily changed as changing social, political, and economic circumstances altered understandings of gender. In the United States, women’s participation in traditional crafts decreased significantly in the 1980s and 1990s as more women began to work outside the home (motivated by either choice or economic necessity) and as the globalization of textile manufacturing made clothing cheap and readily available. When young women in the United States began taking up knitting and other needlework in significant numbers in the early 2000s, scholars like Ricia A. Chansky (2010) noted that participants in this craft revival were still engaging craft as a form of meaning making, but also redefining the meaning of craft in the process. Writing about the trend of women in their twenties and thirties taking up new craft hobbies, Chansky argued, “These women are returning to domestic arts such as knitting and quilting with a sense of strength, not servitude, viewing the needle as a means of creative outlet that communicates their individual strength” (p. 681).

While the meaning of craft has changed for many women in industrialized nations where their participation in craft is determined less by necessity or expectation, it would be overly simplistic to imagine that contemporary engagement with craft is motivated by women’s desires to see themselves as free and empowered in opposition to their foremothers. In a study of how contemporary knitters understand both their craft and their own identities as crafters, Stella Minahan and Julie Wolfram Cox (2010) found that many of their participants understood their knitting as a way to connect to previous generations of women, finding strength and connection (even if those connections were based on nostalgic and romanticized images of the past) to help them cope with the pressures and struggles of life in late capitalism. Faith Kurtyka (2016) found that members of a newly formed sorority used craft as a way to negotiate both their identity as a group and their position to long-standing sorority traditions. Kurtyka argued,

While it would be a stretch to say that the ideologies of crafting allow for radical or disruptive gender roles, the creation and implementation of a vision for an artistic project—a practice of crafting—frees the women from some of the stigmas and expectations attached to sororities. This crafting practice also challenges them to collectively generate and implement an alternative vision for what a sorority might be like and who sorority members might be. Through the material and discursive practice of crafting, the women are able to imagine other modes of existence for themselves and the sorority. (p. 34)

Thus, even as the cultural meaning of craft has shifted and will continue to shift, it seems that the process of engaging craft still functions as a meaningful site for participants to carve out individual and collective understandings of identity that are less bound by the dominant culture.

But the rhetorical power of craft is not contained in the process of making alone. The material aspects of craft remain a vital part of its discursive and epistemic constructions, which are made tangible in the objects produced and are enabled by the bodies that produce them. Indeed, as Goggin (2009) noted, “[B]odily knowledge is as important, if not more so, than vision and cognitive knowledge in embroidery—the feel of the fabric, thread, and needle, as well as the movement of the hand, require a kinetic familiarity” (p. 4). Whatever knowledge and meaning is produced or negotiated through craft, then, only emerges through the interaction of body and mind, and through the context of the crafter engaged in domestic work but also necessarily immersed in the wider world. Indeed, scholars like Bratich and Brush (2011) have noted that one of the things that is significant about the current craft revival is the way that it collapses so many of the binaries that have traditionally structured understanding. In her work on yarn bombing, Goggin (2015) echoed this sentiment as she explained, “For many crafters, hand work is a dynamic response against the separation of labor and domestic skills, the split between public and private, the disconnection between producers and consumers, and the other binaries rendered by modernity and the industrial age” (p. 145).

While many feminist scholars have explored the way that craft has allowed women to expand both the meaning of their material productions and their understanding of their situated identities, scholars like Maura Kelly (2014) have warned against assuming that contemporary craft communities are necessarily informed by feminist politics, having found in her ethnographic research of contemporary knitters that the meanings ascribed to knitting were contested and sometimes even deployed towards explicitly anti-feminist ends. In her study of handmade clothing, which she termed “folk fashion,” Amy Twigger Holroyd (2017) reaffirmed the call to avoid overinvesting in the transformative potential of craft as she wrote, “[I]t is important to acknowledge that the experience of wearing handmade clothes is often less positive than we would hope. There are anxieties associated with contemporary fashion, and because handmade clothes carry conflicting meanings—being seen as creative and desirable in some contexts, old-fashioned and unappealing in others—there is a danger that folk fashion could exacerbate these anxieties” (p. 187-188).

These calls for caution are apt given that the meanings around craft, both in terms of the process and the artifacts created through those processes, are shifting, contextual, and contested. But the fact that these meanings are in a continual state of negotiation is itself rhetorically interesting, frequently prompting reflection on the part of the maker throughout the process of making and through the use of the artifacts created. Comparing her research on contemporary sewists to Kelly’s enthnographic study of contemporary knitters, Bain (2016) argued, “Unlike Kelly’s knitters, in the case of sewists there is a great deal of evidence that sewing […] encourages participants to critically consider their craft in a range of ways, including (though not limited to) its relationship to feminism” (p. 64). As we consider the transformative potential and rhetorical power of handmade clothing, it is important to bear the contested meanings of craft in mind while also clearly situating the individual experience of the maker, which is what I aim to do with my own experience in the following section.

A Struggling Academic Makes Clothes

I have been a regular crafter since I learned counted cross stitch at the age of five or six, but I did not start actively making my own clothes until I was well into my doctoral program. My graduate school experience was one of intense conflict. Like many who go to graduate school with the aim of becoming an academic, I was a high-achieving student who was intellectually curious and had largely enjoyed the research work I had done up until that point. During my Master’s program, I found myself energized by and deeply invested in teaching. But a PhD program is a process of being disciplined (not just in the sense of exhibiting discipline, but of being brought in line with the norms, values, and expectations of the discipline) and of professionalizing, and I struggled with both.

I was in a competitive program that was training me to be a researcher first and foremost, but was realizing more and more that I cared primarily about my teaching. Faced with a choice between two distinctive tracks in my program, I pursued an emphasis in rhetoric based on work I had done during my MA program, which kept me out of composition theory courses that might have fed my interest in pedagogy. Because I was seen as a promising student, I was awarded a fellowship releasing me from teaching responsibilities for two years. I felt proud of the achievement but also found myself struggling as I was disconnected from the teaching work that had become my primary point of motivation to earn my doctorate in the first place. I had taught myself to knit during my first year of college using Debbie Stoller’s now-iconic Stitch n’ Bitch: The Knitter’s Handbook (2003) and had relied on knitting as a way to process stress and overwhelm throughout my BA and MA. But now the ceaseless pressure to work made me feel guilty about my knitting and turned what had previously been an important source of comfort and release into a fraught enterprise.

I wanted desperately to do well, but found myself faced with expectations and demands I didn’t know how to satisfy. My sense of self and my sense of purpose quickly started to erode, leaving me in a state of debilitating depression and anxiety. I worked hard to manage my mental health issues to the best of my ability and kept advancing, however tenuously, through my program. But the pressure and sense of unease only grew the farther I progressed, as I received increasingly specific advice about how I needed to present myself as an academic and the kind of profile I needed to develop as a researcher. It felt as though I was being given a hard set of rules to follow—a kind of pre-packaged identity that reflected the kind of person who could succeed in the academy. And that rigid definition of success seemed to leave little room for my own desires, goals, and creative ambitions.

Alongside this sense of groundlessness and anxiety, I became increasingly aware of how my body was being interpreted and how it figured into the disjunct I felt between who I was and the academic mold I thought I was supposed to fit. I felt intense pressure to present a professional version of myself but struggled just as intensely to figure out what this meant and what it would look like. I identify as female but think of my femininity as distinctly queer and androgynous. I have always gravitated towards casual, utilitarian clothing because its gendered distinctions seem less marked. Despite the fact that so much of what is considered professional clothing plays off of masculine ideals of what it means to be “professional,” it rarely achieves the understated androgyny of casual clothing and instead tends to clearly mark and distinguish masculinity and femininity.

My struggle to find clothing to help me present a professional version of myself was only exacerbated by my size. At the time, plus-size clothing options—especially workwear—were incredibly limited. The selection available in stores was scant, overpriced, and targeted towards middle-aged employees working in conservative office environments. More youthful professional styles were becoming increasingly available through online retailers, but I found these options almost all privileged a traditionally feminine aesthetic that I could not embrace. While basic styles like dark pants and solid button-down shirts were often available, I battled ill-fitting cuts that were uncomfortable, required constant adjustment, or simply made me feel sloppy.

As a graduate student, I was not handed a clear dress code to follow, and I saw the faculty in my program and across the rest of the university construct their professional identities through their clothes in a variety of ways. But it was still clear to me that there were risks to mimicking the “jeans and sweater” uniform I’d seen so many of my male professors embrace. As Katie Manthey (2017) notes, “In academia, dress codes and dress practices are often talked about anecdotally. Although many institutions of higher education may not have formalized dress codes for faculty, this does not mean that bodies are not normed based on appearance” (p. 202-3). As a fat, queer woman with very little institutional power I worried constantly about how to dress myself in ways that projected authority in the classroom, within my department, at conferences, and during interviews. But how was I supposed to do that when, on a practical level, the available options rarely fit my body or my identity? And on a more abstract level, how was I supposed to dress in ways that represented who I was when I was struggling to keep hold of my sense of self? How do you build a professional wardrobe when you don’t have a clear sense of how you can or should fit yourself within your profession?

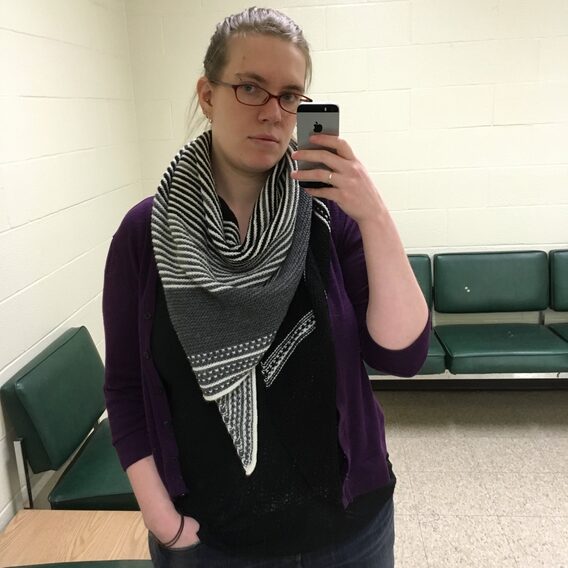

|

Figure 1: Modeling one of my first fully handmade outfits.

It was against this back drop of anxiety (over my body, over my identity, over where I fit within my field) that I got serious about learning to sew. I had actually been sewing on and off since I was a kid, picking a project up and sometimes finishing it, sometimes leaving it for my mom to finish, sometimes trashing it because it simply didn’t work out. I’d owned a sewing machine since my dad gave me one for my 17th birthday, but I had used it infrequently and found it more a source of frustration than joy. I’d had every intention of getting serious about sewing since high school, harboring great dreams of building a unique, personalized wardrobe. In the margins of my class notes, I doodled designs of the garments I wanted to make myself once I mastered the sewing machine. In college, when I was bored and avoiding homework, I’d scan through sewing pattern offerings online. And, in the end, I sewed very little and most of the things I did make turned out badly.

But while I was studying for my comprehensive exams, I found myself standing in the middle of Target, mortified and angry because I needed new underwear and couldn’t find any. All of the available styles topped out at a 42” hip measurement, which was ten inches shy of my measurement at the time. This was not the first time that I’d been disappointed at not finding my size in the store, but it was the first time that I’d found myself unable to purchase a very basic—literally, foundational—garment in person. My only option was to order something online from a plus-size retailer, at four to five times the cost of what I had hoped to purchase in the store. Not being able to buy jeans from Target was inconvenient but hadn’t bothered me during the handful of years when that had been the case. Not being able to buy basic, no-frills underwear felt personal and degrading.

In my anger, I resolved to sew my own underwear. I knew this was possible and achievable because throughout my many years of wanting to sew, I had followed a handful of sewing bloggers, at least one of whom had sewn her own underwear from recycled t-shirts, released a free pattern for basic low-cut briefs, and had published a clear photo tutorial outlining each step for constructing a durable, well-made pair of undies. The free pattern, of course, also topped out at a 42” hip measurement, but I found another independently-published pattern in my size that I was able to purchase for $12—roughly the cost of a single pair of underwear from a plus-size retailer. I pulled out some old t-shirts my partner and I had set aside for various reasons, cut out my pattern pieces, fought to master fold-over elastic, and within a few months, I’d outfitted myself with a drawerful of handmade underwear.

When I passed my exams, I celebrated by upgrading my finicky bottom-of-the-line sewing machine with a mid-grade workhorse machine that could handle upholstery weight denim as easily as a thin and slippery silk fabric. I dove into making new garments with abandon, sewing everything from t-shirts to jeans to jackets. I even found myself reinvigorated by my knitting, and threw myself into an intensive effort to learn to knit perfectly fitted and professionally finished sweaters. I was hooked on making clothes.

Of course, this didn’t immediately solve all my problems. I didn’t learn to sew and then suddenly have an entirely new wardrobe. I was limited by time, by the shoe-string budget that comes from living on a graduate stipend, and by my novice skill set. Many of my early projects were technically flawed, poorly fitted, or made with fabric that didn’t stand the test of time. Adding handmade garments to my wardrobe was a slow and tenuous process, and my desire to make the professional wardrobe of my dreams far outpaced what my hands were able to accomplish. But I found that I didn’t actually need to achieve a closet full of bespoke, unique garments that perfectly represented who I was to find myself feeling more grounded and whole.

As a graduate student studying feminist rhetorics of the body, I was working with theories critiquing the Cartesian tradition and the way that it rejects, ignores, and even abuses the body. And yet, the pressure to achieve and to discipline myself into being a model researcher left me depressed, anxious, and disconnected from my body. At the same time that I was a writing teacher professing the value of the writing process, I was also trapped in the mindset of privileging the end product of professionalism. I saw myself as a CV—a list of achievements to detail in an application letter—and I compared myself to the products of other’s professional achievements. Just as the privileging of mind over body decontextualizes thought from the materiality that shapes it, the privileging of product over process erases everything that is valuable about how things come to be. As an embodied multimodal rhetoric, the act of making my own clothes helped collapse these binaries in a way that transformed the way that I saw myself and the professional life I could imagine.

As I knitted and sewed, every project created space for a small transformation in which the movement of my hands and the tactile knowledge I was cultivating helped me learn, deeply, the lessons that I could not internalize through theory alone. Wherever I sat sewing or knitting became a meditative space in which my mind was fully focused on the act of creating, or where I was able to quietly process the feelings I was struggling with and define what I wanted from my work on my own terms. Every project was also a small step forward in my goal to create a wardrobe that felt reflective of my identity and, as such, a reminder of how progress is made slowly. Every shirt gets constructed step-by-step. Each technique is refined slowly, over time, with practice. With each mistake—every seam that needed to be picked out, every fit adjustment that didn’t quite work, every inch of knitting that needed to be unraveled and redone—I appreciated more deeply the vital role that failure plays in learning.

|

Figure 2: The first version of this sweater, knit according to the pattern instructions, didn’t turn out the way I had hoped. But I ripped the sleeves and hem back and reknit them, making adjustments that resulted in a sweater I wore constantly.

These are things I told my students as a writing teacher, and things I should have already learned through my own writing. However, they were lessons I could only internalize in a deep and meaningful way outside of the pressures of academic work and through the movement of my hands as they pieced together fabric and looped stitches through my knitting needles. The slow, physical process of garment-making helped me cultivate a tolerance for failure and helped me learn to respond, instinctively, with reflection and an eagerness to try again rather than with despair. But garment-making also changed the way that I looked at the world, shifting my perspective from seeing end-products to wondering how things were made. A rack of clothes that had previously represented the limited range of available options became but a set of artifacts to investigate for new construction techniques or an interesting set of design choices to draw inspiration from. For me, this was the most radical lesson of garment making. Sewing and knitting my own clothing became a lived, embodied rhetoric of possibility—a way of seeing and interacting with the world as crafted and constructed, as shifting and changeable, as made and remade through our interactions.

As I slowly built up my handmade wardrobe, the clothing that I produced wasn’t earth-shatteringly unique—my style has always been basic and reserved. But it fit my body and it didn’t feel like wearing a mask. And more than that, it was a tangible reminder of the important lessons I was learning about work and growth through the process of craft. At some point, while I was struggling to make progress on my dissertation, I looked over at my sewing machine and the half-finished project lying beside it and realized that what I most wanted was to be able to approach my academic work the same way I approached making clothes. In my career, as in my craft, I wanted to approach a challenge with the energizing feeling that if I could simply break it down into clear steps and practice the right techniques, then there was really nothing I couldn’t do. I wanted to feel confident that if I came up against a set of unsatisfactory options, I could simply make something that would fit my life better. The calmer headspace that came from knitting and sewing helped me clarify what I wanted my professional life to look like, and I worked deliberately on applying my “craft mindset” to slowly but continuously making progress towards those goals.

|

Figure 3: I made this simple black cardigan when I had been sewing for about a year, and ended up wearing it to a job interview.

By the time I went on the job market, I was feeling much less conflicted and more confident about my future in the academy. But I had only been sewing seriously for two years and was not feeling confident enough in my skill level to rely on handmade clothing for interviews. I went to the plus-size section of Macy’s, hidden in a far corner of the basement level, and sifted through racks of what my partner described as “sad clown clothes.” I eventually found a shirt I could live with and a waterfall-front blazer that I hated but would at least match a pair of pants I already owned. My first interview went well enough, although I felt awkward and uncomfortable in my jacket all day. While I had been encouraged to present myself in a way that made a statement about who I was as a professional, my interview outfit that day was really just a question mark. I felt as though I were playing dress up, miming what I thought a professor was supposed to be and anxious that I was getting it all wrong. But the significance of dress practices exceeds the question of whether or not we fulfill a dress code. I may have been appropriately dressed on paper, but I could not see myself working in the department where I was interviewing. Part of that might have been that it was simply not the right job for me, but part of it was feeling like the way that I was presenting myself was promising a version of a self that I could never deliver.

On the morning of my second interview, the anxiety of the months-long job search combined with poor sleep and interstate travel finally broke down my lingering concerns about interviewing in handmade clothes. I desperately wanted the job, but I also desperately needed to feel comfortable and at home in my body. On a whim, I swapped out the professional but deeply-loathed jacket for a simple cardigan I’d sewn for myself a few months earlier. The fabric was soft and light but warm. The lines were clean and simple but modern. I worried that I would look unprofessional and like I wasn’t taking the interview seriously, but the cardigan made me feel steady, at ease. As I moved through various campus buildings, shook hands with one person after another, ate with strangers, and demonstrated how I worked as a teacher, I was neither conscious of my body nor disconnected from it. I did not feel like I was wearing someone else’s clothes, performing someone else’s version of the role of professor. I felt confident in the way that I was presenting myself, but that confidence did not simply come from the fact that I was wearing a garment tailored to my body and my style. That confidence came from feeling firmly rooted in all of the lessons about failure and possibility that I have learned from making my clothes by hand. I got the job.

Handmade Clothing and an Embodied Rhetoric of Possibility

As discussed earlier, the various meanings ascribed to craft and the various ways that identity is negotiated through the process of craft shifts in relationship to different economic and cultural contexts. Like many garment makers in the United States, my own experience of sewing and knitting my own clothes is understood in relationship to what is (and perhaps more importantly, what is not) made available through mainstream clothing retailers, as well as in relationship to the highly exploitive and environmentally unsustainable manufacturing processes through which most clothing on the market is produced. In her book Folk Fashion: Understanding Handmade Clothes, Holroyd (2017) elaborated a theoretical framework for understanding handmade clothing that focuses on fashion as a form of identity construction and as a vehicle for connecting with others. Holroyd’s framework described fashion as a commons—incorporating all forms of dress across time and context, and ideally open to all as a wide and shifting field of options from which we can pick and choose as we work to present whatever version of ourselves we want.

But Holroyd quickly and insistently pointed out how constrained the ideal of the commons becomes as it is shaped by the economic and normative interests of the fashion industry. As she wrote, “I believe that it is important for us to have an open and accessible fashion commons in order to construct our identities and connect with others most effectively. However, I am concerned that mass production and industrialization have ‘enclosed’ this commons, restricting access to styles and knowledge and limiting our ability to act independently” (12). In other words, despite the frequent insistence that we have more clothing options at our fingertips than ever, the influence of the fashion industry and the normative power of late capitalism have actually restricted the available options, resulting in a sea of sameness and stylistic homogeneity. The enclosing of the fashion commons is significant not just because it limits our ability to select personal styles that feel representative of our unique identities, but also because in doing so, it limits how we are able to present ourselves to others and reinforces the privileging of normative identities (which are made intelligible through the enclosed commons) and marks non-normative identities as such (by heightening their divergence from the expected norm).

As was my experience when I struggled to define what professional dress meant to me in my own context, cultural and disciplinary expectations of what constitutes professional dress and professional identities are almost always presented as finished products—as models, as sample outfits, as packaged examples of the kinds of looks and goals we should aspire to. Even if those examples might be achievable for us, only seeing the end product obscures the process of getting there. And in many other cases, the example doesn’t seem achievable at all or seems to completely ignore the very real barriers or obstacles people might face in meeting those expectations. This product-focused approach pays little attention to how those models or examples might be broadened or adapted for different identities or circumstances. The models, whether in the form of suggestions for interview outfits, professional wardrobe capsules, or models of professionalism in our field, can start to feel like rigid monoliths—ideal routes to success that can only be easily accessed by certain people. Like the enclosed fashion commons, the message created by these rigid monoliths is that the field itself is enclosed. Ongoing discussion of the value of diversity and the importance of creating inclusive spaces makes it seem like the possibilities are endless, but the repetition of and reliance on a limited version of what it means to look professional continue to discredit and delegitimize non-normative bodies. It is easy to lose sight of the fact that these ideal models—ideal versions of what it means to be professional—are constructed, that they are artifices that heavily shape our experience but which can still be interrogated, shifted, remodeled, rebuilt. The question now is how to cultivate an embodied multimodal rhetoric that can begin to open the enclosed commons and shift focus to the process of construction. Certainly, this cannot and should not be accomplished through a single means, but I would argue that wearing handmade clothing can contribute to the project by creating a visible of what is possible—by reminding us that we can make and remake our professional fields and our places within them.

Jenny Rushmore (2015), a sewing blogger and co-founder of an online community for plus-size sewists called The Curvy Sewing Collective, spoke to the way that making her own clothes completely reframed her body image precisely by helping her see the greater range of possibilities available. Giving her access to well-fitting, beautifully made clothes that fit her style for the first time, sewing helped Rushmore disentangle her sense of worth from her dress size and to see her style as within her control. As she explained, “It turns out that in many ways sewing your own clothes is a radical act; a chance to escape the constraints of the fashion industry, whether in style or size, and an opportunity to express yourself exactly, rather than choosing from someone else’s expressions. Your physical dimensions become simply a numerical input and not a value judgment.” In Rushmore’s story, having access to the material alternatives to limited mass-produced clothing options is important, but much of the empowerment and sense of possibility that comes with making your own clothes is accessed through a deep engagement with the process. It wasn’t just having a closet of stylish, well-fitting dresses that mattered to Rushmore—it was that she exercised agency through each step of the process, from selecting patterns and fabric, to choosing construction and finishing techniques while gradually building her skill set as she did so. Von Busch (2014) argued that this agency in the process of making is vital to the transformative potential of handmade clothing. In “Crafting Resistance,” he wrote, “Obeying fashion without conscience is the same as obeying laws we have not set ourselves. By putting our conscience back into the equation, we can remind ourselves of our autonomy. Taking on fashion through craft is more than an issue of expressing identity; it is a way to tackle our relationship to our compliance to being governed. It is a way to be free” (p. 77-78).

|

Figure 4: Modeling a shirt I made and wore during my most recent Me-Made May experience.

Certainly, my own experience of making clothing became a way to address my own “compliance to being governed,” both in terms of how I oriented myself towards the disciplinary expectations of my field and the normative standards of “professional” dress. Anchored through my own bodily movements in the process of making, the seemingly monolithic models of what it meant to be professional and successful in my field started to break down in my own mind as the work and rhythm of my hands helped me internalize the fact that everything is built through process, and that every process can be broken down into manageable steps. My failures in my sewing and knitting made me more resilient in the places in my professional life where I experienced more pressure because I had repeatedly practiced the process of failure, reflection, and revision in a tangible, low-stakes way. I stopped fixating on the discrete achievements and rigid expectations idealized by others—I stopped accepting without conscience the options being presented to me and instead, through the model of my craft work, figured out how to bring my conscience and agency back into the process of defining what I wanted my professional life to look like, both in terms of the work I did and the way I presented myself through dress. The intellectual and emotional work of redefining my relationship to my discipline and the ideals of my graduate program did not happen in the classroom or in my research or in meetings with my advisors. It happened while I was cutting out patterns, threading needles, manipulating fabric, and knitting through rows of stitches.

But to only focus on the way that engagement with the process of making reframes the maker’s relationship to power and identity would be to oversimplify the transformative potential of handmade clothing. Indeed, handmade clothing dramatizes the circular, symbiotic rhetorical relationship between process and product. What is gained in the process of making is remembered, relearned, and paid forward in the act of wearing the clothes. The process of making the garment might start to reframe our individual identities or our relationship to power, but wearing and displaying what we make integrates those changes into the way that we connect with others and the way that we interact with the spaces and spheres of influence in our lives. In 2010, British sewing blogger Zoe Edwards (2019) started an online challenge called Me-Made-May with the goal of encouraging “those who make their own clothes to develop a better relationship with their handmade wardrobe.” Motivated by an internalized anxiety about how her handmade clothes might be stigmatized for their imperfections, Edwards set out to wear handmade clothing every day during the month of May, documenting her effort on her blog, and inviting others to set their own pledges for wearing and reflecting on their experience of wearing their handmade clothes. The challenge has continued every year since, expanding widely in terms of its participants and the online audience those participants reach.

Over the years, as participants document how they wear their handmade clothes and how they feel about wearing the garments they have made, they reflect on and engage in critical conversations about a range of topics including body image, mental health, the fast fashion industry, sustainability, professional dress codes, motherhood, aging, personal style, the lack of visibility of plus-size sewists, and the influence of consumer culture in craft communities. The act of wearing handmade clothing is not simply a vehicle for these conversations; it is a material reminder of the fact that we are always embedded within these conversations. The act of wearing handmade clothing provides new pathways to rhetorical agency within these conversations where we can collectively negotiate meaning and our relationship to power. Shortly after the first Me-Made-May challenge in 2010, Edwards revisited her anxiety over the imperfections in her handmade clothes. Explaining her changed relationship to imperfection, she wrote, “I am far more forgiving of the homemade-y elements of my clothes because they exhibit the truth that it is possible to avoid mass-manufactured clothing. That badly applied bias binding or concealed zip reminds me that I am contributing, in some small way, to the debate about our culture’s sustainability.” In other words, handmade clothes function as an embodied rhetoric, signaling to ourselves and others that other paths are possible.

Handmade clothes are not just a visual representation of the alternatives we can construct; the very makeup of these garments speaks to the fact that we can claim agency in the processes that shape and create the spaces through which we move. In her article about how sewing her own clothes helped her find her footing in her legal career, Ahmed (2019) wrote, “My pencil skirts buoy me before judges. My knit dresses keep me cozy in the office. The clothes I make support my body as I discuss forms of relief with clients. When I am trying to finesse a legal argument, looking down at my stitches assures me of my ability.” Both by making her feel at ease in her body and by offering a tangible reminder of her competence and ability, Ahmed’s handmade clothes allow her to do meaningful work as an immigration attorney.

|

Figure 5: Getting ready to teach a class in a fully handmade outfit

Like Ahmed, making my own clothes gives me greater breadth in how I choose to present myself as a teacher and researcher. I am not limited by the fashion industry’s narrow ideal of what a plus-size professional woman looks like, and I do not have to compromise my own embodied interpretation of femininity in the process. I can experiment with color, print, fabrication, and style lines in ways that are less constrained by the dictates of trends and traditional gender ideals. Making the clothes I wear to work each day helps me integrate equally vital parts of my life and keeps my work grounded in a fuller, less compartmentalized understanding of myself. My clothes and the process of their construction teach my students and my colleagues important things about me and where I come from, and open up important conversations about fashion, identity, creativity, and making as a form of self-care. The embodied rhetoric of handmade clothing collapses important binaries—process and product, private and professional, practical and aesthetic, domestic and public—making way for new possibilities. It anchors us in the fundamentals of process by providing a visible, tangible reminder that everything is made and can be remade, one step at a time.

References

Ahmed, S. (2019, May 19). How sewing improved my mental health—and restored my professional ambitions. Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/

Bain, J. (2016). “Darn right I’m a feminist . . . Sew what?” The politics of contemporary home dressmaking: Sewing, slow fashion, and feminism. Women’s Studies International Forum, 54, 57-66.

Bratich, J. Z., & Brush, H. M. (2011). Fabricating activism: Craft-work, popular culture, gender. Utopian Studies, 22(2), 233-260.

Chansky, R. A. (2010). A stitch in time: Third-wave feminist reclamation of needled imagery. The Journal of Popular Culture, 43(4), 681-700.

Edwards, Z. (2010, June 20). Thoughts on forgiveness [Blog post]. Retrieved from http://www.sozowhatdoyouknow.blogspot.com/

Edwards, Z. (2019). Me-Made-May FAQ’s [Blog post]. Retrieved from http://www.sozowhatdoyouknow.blogspot.com/

Goggin, M. D. (2009). Introduction: Threading women. In M. D. Goggin & B. F. Tobin (Eds.), Women and the material culture of needlework and textiles, 1750-1950 (pp. 1-12). New York, NY: Routledge.

Goggin, M. D. (2015). Joie de fabriquer: The rhetoricity of yarn bombing. Peitho, 17(2), 145-171. Retrieved from http://peitho.cwshrc.org/

Holroyd, A. T. (2017). Folk fashion: Understanding homemade clothes. London, UK: I. B. Taurus.

Johnson, M., Levy, D., Manthey, K., & Novotny, M. (2015). Embodiment: Embodying feminist rhetorics. Peitho, 18(1), 39-44. Retrieved from http://peitho.cwshrc.org/

Kelly, M. (2014). Knitting as a feminist project? Women’s Studies International Forum, 44. 133-144.

Kurtyka, F. (2016). We’re creating ourselves now: Crafting as feminist rhetoric in a social sorority. Peitho, 18(2), 25-44. Retrieved from http://peitho.cwschrc.org/

Manthey, K., & Windsor, E. J. (2017). Dress profesh: Genderqueer fashion in academia. QED: A Journal in GLBTQ Worldmaking, 4(3), 202-212.

Pritash, H., Shaechterle, I., & Wood, S. C. (2009). The needle as the pen: Intentionality, needlework, and the production of alternate discourses of power. In M. D. Goggin & B. F. Tobin (Eds.), Women and the material culture of needlework and textiles, 1750-1950 (pp. 13-29). New York, NY: Routledge.

Rushmore, J. (2015, August 3). Sewing my clothes is an escape from fashion’s dictates. I no longer hate my body. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/

Sohan, V. K. (2015). “But a quilt is more”: Recontextualizing the discourse(s) of the Gee’s Bend quilts. College English, 77(4), 294-316.

Stoller, D. (2003). Stitch ‘n bitch: The knitter’s handbook. New York, NY: Workman.

Von Busch, O. (2010). Crafting resistance. In B. Greer (Ed.), Craftivism: The art of craft and activism (pp. 77-79). Vancouver, BC: Arsenal Pulp.