Exposing the Seams: Professional Dress & the Disciplining of Nonbinary Trans Bodies

GPat Patterson, Kent State University-Tuscarawas

and

V. Jo Hsu, University of Arkansas

“In an ideal world how you look doesn’t matter. But academia is far from an ideal world, as we know all too well. You want to blend into the faculty ‘identity’ as seamlessly as possible.”

– Karen Kelsky, “On to the Conference Interview!” The Professor Is In

Karen Kelsky, the writer and (tenured) ex-academic behind The Professor Is In has an entire blog series on “What Not To Wear” in academia. Kelsky’s book on academic professionalism has become standardized training for graduate students throughout many universities, and she has built an alt-ac career on demystifying academic professionalization. In “What Not to Wear,” Kelsky details the unspoken strictures of “professional dress” from graduate school, through the gauntlet of job market interviews, and into one’s assistant professorship.

With few caveats, Kelsky’s “clothing rules” are strictly gendered. Men, she advises, should buy a “new suit fresh for the interview season … tailored so that the sleeves and pants hit [them] at the proper spots.” Women, she adds, must also buy new suits that are “stylish, well-cut, [and] fitted,” but not black, “which can be too severe.” Only as an aside does Klesky hint at gender-nonconformity, suggesting (however vaguely) that “butch dykes and transgendered [sic] candidates will have other requirements.”

In an additional fashion blog post, Kelsky (herself a femme) references both Ellen Degeneres and her “old school butch dyke” partner to suggest that butches not hide who they are during the interview process. She closes her blog by linking to the prohibitively expensive UK-based Butch Clothing Company. A cursory perusal of the company’s pricing chart (right) invites further questions about Kelsky’s ability to “read the room.” Few grad students can afford the price of an airline ticket (or conference fee) for a job interview—let alone a bespoke suit worth more than a month’s salary.

The “other requirements” Klesky references for transgender candidates never again surface. Ostensibly, with her caveat about butches now complete, Klesky assumes that her sartorial advice covers all bases. Nonbinary, agender, and genderfluid candidates––many of whom identify as neither masculine or feminine of center—are left to interpret these binaristic expectations of professional comportment on their own.

|

Figure 1: A sample of prices from Butch Clothing Company.

Of course, Kelsky is not individually responsible for the stuffy, elitist notion of academic professionalism that suffuses her advice. We recognize the value in codifying and thus making legible the unspoken rules that govern respectability politics in higher education. While such unspoken rules pervade the academy, we illustrate how these standards become exaggerated during three moments of academic space-time: when one is “in a PhD program,” “on the job market,” and “on the tenure-track.” When we focus on training newcomers to “fit in,” rather than examining the design and limitations of that fit, we end up reifying the very standards that undergird extant social hierarchies and, in turn, exacerbating a climate of precarity and disposability in higher ed. Advice like Kelsky’s brings into high relief the ways the academy’s imaginary amplifies ableist, racist, cissexist, classist, heterosexist, and sizeist social norms that render some bodies as unimaginable and thus incapable of embodying any form of professionalism. Because these mechanisms of exclusion often operate outside of direct verbal exchanges, we require an analytical vocabulary attuned to the rhetoricity of embodied, multimodal gatekeeping and its attendant resistance. In this essay, we take "dress" to mean all forms of professional comportment, extending beyond (though inclusive of) actual attire. Rather, the appearance of "professionalism" is produced and regulated by a vast network of behaviors that demand further scrutiny and re-evaluation.

The following essay further explores the many manifestations of professional dress and its exclusionary assumptions through a series of “loose threads.” These are individual anecdotes with which we will stitch together a broader understanding of academe’s social fabric. In writing out our own experiences and attending to one another’s, we offer a collaborative exploration of academic professionalism and its implications for nonconforming faculty and students. Of course, we could not provide an exhaustive account of marginal experiences in the academy, but we hope that by making space for one another’s stories, we invite further considerations of how unspoken standards perpetuate extant social hierarchies.

|

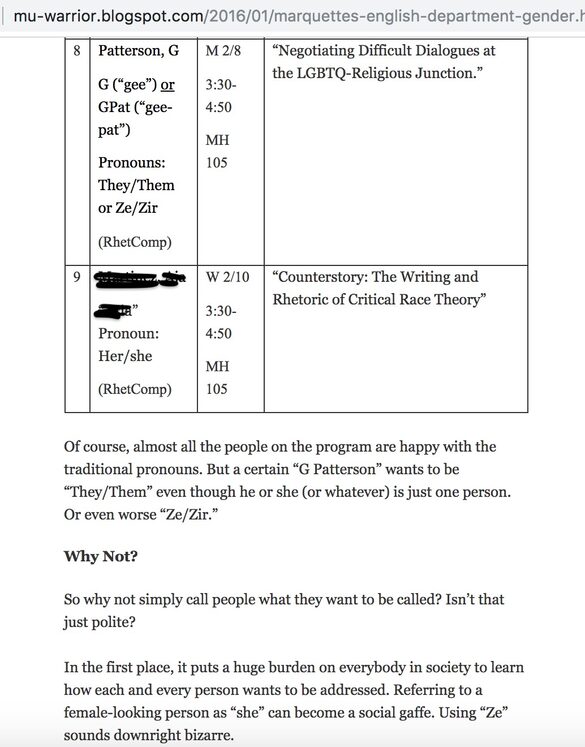

Figure 2: A model for dialogic storytelling.

Method: Dialogic Storytelling as Sewing

In keeping with the textile themes implied in professional dress, we encourage readers to visualize our method of dialogic storytelling in terms of machine-sewing, in which two pieces of cloth are brought together with a top stitch and a bottom stitch (and then finalized with a backstitch) in order to create a seam. Below, we present six woven narratives (pieces of fabric, if you will) in which we recount our experiences navigating professional comportment as multimarg enbies. Engaging in what Ratcliffe (2006) and Booth (2004) describe as rhetorical listening, we identify common threads and stitch them together to create three different seams. This work of stitching enables us to “accentuate commonalities and differences” (Ratcliffe 1999, 204) among experiences while also cultivating a “broader cultural literacy” (207).

Our emphasis on seams here isn’t just a heuristic for understanding our organizational strategy; it is also an important rhetorical device. In higher ed, successful professional comportment is understood to be seamless, natural. In contrast, we see rhetorical work as exposing the seams—the ableist, racist, classist, cissexist, and heteropatriarchal expectations of professionalism (masquerading as neutral, natural, seamless—which press so painfully against our bodies). Throughout, we use footnotes to echo and emphasize such moments of tension in each other’s stories. Jo’s remarks will appear in green times new roman font, and GPat’s are in purple trebuchet font. Finally, just as in sewing, we finish with a backstitch, putting our narratives both in conversation which each other and with theorists like Sara Ahmed (2012), Dean Spade (2010), Gutiérrez y Muhs et al. (2012), and others to illustrate the ways that academe both desires and punishes difference. Throughout, we map the ostensibly neutral (or altogether unspoken) guidelines for professional comportment, illuminating their operations as one of many mechanisms through which difference is regulated and punished.

Seam 1: Made to Fit

This seam traces the thread of “fit” in both physical and social spaces. Prospective students and faculty are often advised to consider whether a campus feels “like a good fit.” Campuses, like clothes, though, are already designed with particular bodies in mind. For those who live and move outside the presumed norm, “fit” becomes a manner of exclusion. Institutions that expect all newcomers to fit extant patterns and expectations are operating under an inherently conservative and assimilationist framework. The following stories explore how these two ill-fitting academics have tailored, at times, ourselves to our surroundings, and at others, our surroundings to ourselves.

GPat’s 1st Thread: “Not a Good Fit”

So much of the discomfort I’ve encountered in professional spaces stems from rigid assump-tions of what professional bodies ought to look like. Professional bodies are assumed to be easy to read and easy to place. I’m not easy to read: I have been read as a woman, other times as a man, but I am neither. I have been read as gay, but I am actually pansexual. I’m often read as white, and indeed I am, but I am also multiethnic. I have been read as middle-class, but I have a working-class positionality. I’ve been read as neurotypical, but I’m dyslexic. And though I am a forty-year-old professor, I am still often read as a student. All this to say, because I can be difficult to read, I am also often read as out of place—as not a “good fit.”

|

| Figure 3: Image of a tweet by GPat. |

In grad school, among my cisgender queer friends, my embodiment was frequently the subject of conversation: “What’s your thing? Are you butch or femme?” My attempts to situate myself as genderqueer (a decade before the term nonbinary came into popular consciousness) were repeatedly reframed in ciscentric terms as “punky queer androgyny.”

Faculty, on occasion, also fixated on my gender comportment—especially as I prepared for the job market. During a mock interview, grad faculty’s critique of my performance had little to do with my answers to their questions. First, they focused on my outfit—which, they observed, might be more fitting if I’d set the look off with a pair of heels. Then, contradicting their initial comments about my lack of femininity, their second critique highlighted my excessive femininity: my voice, they observed, seemed “too high” for my gender expression.[1]

Such discomfort about my gender incongruity would later, on the job market, be echoed in micro-aggressive comments by search committee members. I watched while peers with fewer pubs and fewer teaching/research awards got snatched up by departments. Meanwhile, the only follow-up responses I received after interviews (when I was contacted at all) explained that I “just wasn’t the right fit” for their department culture.

Applying for non-tenure-track jobs, I learned, didn’t open a person up to the same embodied scrutiny. This makes sense. Since NTT faculty exist at the bottom of departmental hierarchies, they tend to be ignored. Indeed, in the five years I spent working on the non-tenure-track, I encountered just one instance of blatant cissexism (a department chair who responded “What? Are we living in APA format now?” when I asked him to introduce me to the department as G Patterson, instead of using my legal name). Indeed, if it weren’t for the job precarity nontenure-track faculty face, I’d likely have never applied for a tenure-track job again. But I did. And, once again, my dread about professional embodiment was waiting for me.

During my second round on the market, though, I decided to do professionalism on my own terms. Having soured on oft-shared guidelines about attire, I sought out an alternative dressclothes literacy. I followed lgbt fashion accounts, like Qwear, DapperQ, and i_dream_of_dapper on Instagram.[2] I reached out to lgbt friends, who were kind enough to open their closets to me. And I read just about every trans blog I could find to discern which fashion choices would work for my 5’9”, 200-pound frame.

My eventual look resulted in a swishy Mixter Rogers vibe:[3] short curly pompadour; gauged earrings; makeup; glasses; “women’s” perfume; gray and blue (not black) men’s dress pants; clearance-rack springtime floral dress shirts; coordinating floral-print ties boasting pink, yellow, and purple blooms; and tight-fitting sweater vests (in lieu of blazers).

But because literacy is about process—not product, it feels important for me to resist a tidy happy story and instead expose the seams (the skipped stitches, the tangled undersides) of my fashion journey. For example, it seems worth mentioning the ways in which I was read as out of place in gender-segregated spaces: the clerks in the men’s department who’d ignore me even when I’d ask for help—or the clerks in the women’s department whose emphasis on help in “How can I help you” indicated not only an unwillingness to help but also a warning that I’d better leave before mall security arrived. It seems worth mentioning my encounter with a recommended local tailor, who placed a witnessing tract in my hands and shoved me out of her shop. It seems worth mentioning the TSA extra pat-downs I received, every goddamn time I flew to an interview. It seems worth mentioning the scowling deans, the frequent misgendering, and the super awkward commentary about which bathrooms I’d use during campus interviews. My wardrobe, forged like so many pieces of armor, does little to deflect the bullshit I navigate in professional and other gender-segregated spaces—but it does allow me to flout expectations of professional embodiment with a defiant, trans enbie, queer differánce. [1] Jo: As an actor throughout high school and college, I was often told that my voice was “too low” for the (women) characters that I was supposed to be playing. I spent countless hours with coaches training me to use the higher register of my voice. Even now, in uncomfortable situations, I catch myself unconsciously tapping into that register as if still trying to inhabit a role not made for me. [2] Jo: I love these! My gateway into genderqueer fashion was DapperBoi, though mostly I “window shopped” since their items were beyond my means as a graduate student/postdoc. Your story reminds me of the anecdotes I’ve gathered from organizers working in community arts and writing programs for LGBTQ+ youth of color. I consistently hear from these folks how they have been denied access to knowledge—how none of the mainstream channels through which they were to learn about their pasts and their possible futures had even conceived of people like them (rather, like us). So often the genres through which marginal communities share and build knowledge are dismissed as frivolous or anti-rigor (social media, letters, zines, etc.), but these queer “ephemera” (Munoz, 1996) are the means through which other worlds are made possible. [3] Jo: I so admire this vibe (and your characterization of it).

Jo’s 1st Thread: Not Fitting In GPat’s imaginative, DIY defiance through trans/queer embodiment calls up a story I had long set aside. At the end of my final year of high school, I had grand plans to sneak into my senior prom. I was grounded because my parents and I were fighting about everything but the queer relationship we all knew I was in but none of us could talk about. For related reasons, my only “dress clothes” were actual dresses that I never wore except after losing particularly explosive arguments. For prom, though, I had borrowed a tuxedo from the school drama closet. The vest had lost a button and, in my first-ever self-taught sewing adventure, I managed to stitch the vest to my own pants before managing to undo and redo it all in a hideous-but-functional patch job.[4] I remember that every article of clothing held the perennial musk of the costume closet. The threads were coarse and scratchy. I had to bundle the waist of the pants with a poorly matched belt, and I rolled up the pant legs to keep them off the floor. The vest billowed off my body—as did the shirt, whose shoulders neared my elbows. This is still what I associate with “dressing up”—the sensation of smallness. As a professor, I no longer have to borrow clothes from a costume closet. As an adult who has worked/is working to rebuild a relationship with my parents— to collaboratively rewrite the scripts around (gender)queerness in which we have all been immersed — I no longer own or force myself into dresses. Still, I am 5’2” and somewhere between 120-125lbs now that I’ve stabilized my hypopituitarism. Between my small frame, my ethnicity (Taiwanese American), and the fact that I am relatively young for a professor (30 years old), I was/am presumedstudent[5] in nearly all spaces. In my first year as university faculty, I began setting aside money for more “professional” attire. My professional wardrobe consists mostly of “men’s” dress shirts and pants found online in the smallest available sizes. After too many confrontational “can I help you [out of this store]”s, I buy all my clothes online. Unlike GPat, I never graduated beyond my amateurish button-replacement. However, I am fortunate enough to have found exactly one friendly tailor who helps me shorten pant legs and take in jackets and vests. I’ll never forget the sensation of cinching a vest that’s been fitted to my torso. The fabric was heavy with the density characteristic of “men’s” clothes. The sharp cut of the shoulders gave me a breadth I don’t normally have in “women’s” attire. The tailor had kept the chest wide so I could button the vest without binding, but also pulled the waist in so that the fabric followed the curve of my ribs. It was the first article of clothing that ever held the shape of my body “like armor.”[6] Trading t-shirts and hoodies for collared shirts and ties, however, brought a new set of problems. Whereas bathroom policing was an occasional occurrence in my life before, it is now an everyday concern. Jeans and sweatshirts, as casual wear, get to traverse the gender spectrum with a little more freedom. With more “formal” attire, however, the divisions ossify. In streetwear, I appear androgynous by most people’s standards. Most strangers avoid pronouns when they meet me, and I’m frequently hailed by an apologetic “sir—ma’am."[7] If I put on a $9 tie, though, I am almost always read as male. Much of learning to dress “professionally” has been learning to decode, anticipate, and recode the gendered and classed significations attached to physical appearance.

Figure 5: Image of Jo's office door. I have a general resistance to focusing on bathrooms when discussing trans experience since the topic of bathroom bills has dominated and narrowed the scope of conversations about trans justice.[8]That said, bathroom policing is a very real way that trans and gender nonconforming people are kept out of public spaces. In the bathroom down the hall from my office—maybe twenty steps from the “We Defend Our Trans Family” poster on my door—a woman informed me I was “in the wrong bathroom.”[9] On a regular basis, women will open the door, see me, and turn right back around. I experience inordinate gratitude when I run into a colleague who greets me with a familiar smile. In other buildings, confrontations are almost inevitable. This past August, I was teaching a summer course in the Business building, in a classroom right beside the women’s bathroom. During the class break, I was washing my hands when a young woman entered. Predictably, she pivoted on her heel and retreated immediately. At that point, most women prefer to wait outside until I leave. Some return to demand that I leave, at which point, I respond with my most-polite, feminine-pitched voice to signal that they are mistaken. At which point, the whole affair still becomes my fault. In Houston, a woman blamed it on my hair; the short crop made her assume she could gender me on sight, and that gave her the authority[10] to yell at me. In Minneapolis, my blazer was to blame. In Northwest Arkansas, where I live, it’s this slowly expanding “professional” wardrobe of dress shirts and ties shifting me from one category of unbelonging to another. Like always, I tried to leave quickly. On that particular day, though, the door burst back open just as I reached for it. The woman returned with two friends in tow—another young woman in a (“women’s”) business suit and a young man who looked prepared to confront (/assault?) some imagined offender. Everyone stopped when they saw me, drying my hands, with my strained, let’s-not-make-a-scene smile. The man’s slack jaw and speechlessness made it apparent that I was not what he had pictured. Before his surprise wore off, I darted past the trio and back into the hall. The door shut on their uproarious laughter,[11] but it barely dampened the sound. In another place, in another memory, this is a confrontation. In England, it is a bouncer who grabs me from behind and pulls me out the door. In North Carolina, it’s a near-hysterical woman who accuses me of following her into the bathroom. In the Minneapolis airport, it’s three TSA agents debating quietly about who gets to search me because they’re too embarrassed to ask about my gender. In this story, though, in this place where I work, where I am supposed to be the poised professional, it is none of those things. In this story, I inhale the surge of my heartbeat, exhale the tide of memory, and I reenter my classroom. [4] GPat: There’s something so striking about this—the borrowed vestments from the drama closet and the experience of learning to sew in that space of tension. I can’t help but think about my own story of learning to tailor clothes (also poorly) after that tailor threw me out of her shop. Sometimes I think: to be trans is to develop a keen and embodied sense of multimodal literacy. When the world slams doors in our faces, we develop the skill-sets needed to build new ones. [5] GPat: Too often, faculty dismiss this as a good problem to have: “Oh, live it up while you can—it’s good that people read you as young.” But such responses seem to willfully misrecognize how multimarg fac being read as students is an act of conferred dominance (Johnson, 2006, pp. 23–24). It’s feels like a stealthy way of communicating we don’t belong––that our bodies cannot be imagined as professional. [6] GPat: What a feeling! [7] GPat: Ah, yes: to be “s’ma’amed.” [8] In the words of C. Riley Snorton, “Media focus on transgender people’s abilities to use the bathroom of their choice obscures a more urgent conversation about what modes of dispossession are possible under the ruse of state inclusion” (2017) [9] GPat: A million times yes. And, while I totally understand why you’d be reticent to talk about bathrooms, your sharing this story feels so important––because it emphasizes the need for all-gender bathrooms. For the first time in fifteen years, I’m teaching at a campus that has about 3–5 all-gender bathrooms per building. It’s amazing. And ya know, for all the bathroom panic about the Big Bad Trans, I’m heartened by how many students (of all genders) use these bathrooms without issue. It’s almost as if people go in there… to pee. [10] GPat: This is so real. Julia Serano (2007) refers to this phenomenon as gendering, the compulsive way people rely on superficial visual and audio cues to clock people in order to read them as men or women (p. 163). Your story highlights the entitlement some cis people feel to assess others based on their gendered standards—and the way enbies are set up to fail in such bigender systems. [11] GPat: While most of our footnotes emphasize the connections in our stories, this is an important way in which our stories don’t overlap. My white-skin privilege insulates me from (even the threat of) such physical altercations. I say this to emphasize the failures of whitewashed neoliberal visions of inclusion, which might say, “Well, maybe TSA needs trans competency training.” Nope! Any vision of trans justice that doesn’t center racial justice is flat-out bullshit.

Seam 2: Accessories as Self-Assertion Whereas the first seam explored traditional notions of clothing and dress, we wish to make clear the ways that sartorial politics are socially and situationally dependent. In many ways, the profession dresses us. Most of us are employed by institutions with much longer histories than our own. Those histories have accrued into social and structural patterns suited for particular individuals. In this sense, all of us put on this institutional memory when we become a member of its community—however marginal. To examine this aspect of professionalism, we turn from professional dress to professional comportment. Much like Susan Stryker's concept of gender comportment, we understand professional comportment as the ways we mark ourselves (and are marked) in the workplace beyond matters of attire, as well as how we are disciplined by institutions for our failures to conform to the roles expected of us (Stryker 2008, p. 12). Our narratives below illustrate how failures to adhere to such patterns can render a person unrecognizable—and how certain attempts to alter these social/structural patterns (so as to become recognizable) have the deleterious effect of rendering a person as unprofessional.

Jo’s 2nd Thread: Binary Code(s) In the first week of my first semester as an assistant professor, I couldn’t access my email, the Blackboard pages for any of my courses, or my own office. Though my job contract and all my correspondence with the university identified me as “Jo,” the web management system generated all my university accounts under my legal name.[12] This meant that my students and anyone who interacted with me over email would see my deadname first–a name I no longer use; a name that has never felt like mine, but rather, like the name for someone I failed to become. I contacted the IT department immediately to request a change. Unfortunately, it would take over a week for my new account to be up and running. In the interim, I couldn’t access anything that required a digital ID. Without a digital personhood, I couldn’t use university email or even check out library books. While the university had issued me an ID card with the name “Jo,” the office in charge of distributing keys refused to release the ones to my office due to the mismatch between the name on file and the one on my ID–nevermind that my employee number remained the same, or that I had a driver’s license and credit cards that confirmed my identity. At no point during this series of events did any one person have to think anti-trans thoughts. In fact, it is perhaps the distinct absence of human engagement and imagination that resulted in my exclusion from both virtual and physical university spaces. In this instance, there was already a set of policies and procedures in place, almost entirely automated by computers that input and output in binary code. Without human intervention, it runs independently as a form of trans exclusion. Within that same computer system, the students at this university—at many universities—cannot input a “chosen name” or “pronoun” on their class rosters. When instructors do not ask students for self-introductions on the first day of class, they are more likely to misgender or deadname trans or nonbinary students. Those students must then decide whether or not to out themselves in front of a room of strangers. They must risk the discomfort of their peers and their instructor. They must guess at whether or not the professional in the front of the room will be sympathetic or hostile. Often, they decide that it is not worth the risk—that they are unwilling to be the problem on that first day. So it goes that even the most well-intentioned members of university faculty might have no idea that they are reinforcing a violence with every utterance of a name.

Figure 6: Image from Jo's Instagram profile. The imaginative forms of “accessorizing” that GPat describes below emerge in response to such passive (yet effective) forms of exclusion. So often, people whose experiences fall beyond dominant social grammars need to find ways to (re)mark upon (and thus augment) those rules of engagement. For example: email signatures. Trans and nonbinary folks and allies will include their pronouns in email signatures or other text-based profiles as an attempt to center conversations about gender. Signature pronouns are an acknowledgment that people can never assume someone’s gender based on appearance, vocal tone, or names. They respond to social and institutional norms that do not regularly facilitate conversations about gender identity. It is because strangers will go to great lengths to guess my gender identity rather than ask directly that I must invent (or, some might say, impose) rhetorical situations[13] in which I pre-empt or revise assumptions made about me. [12] GPat: Gods yes! I’ve had to deal with this at every single institution. And you’re right: sometimes the process takes weeks and months––and the entire burden of this process is placed on new faculty members. Some folks might say (as they have to me): “Well, why don’t you change your name?” But that misses the point that (1) we shouldn’t have to and (2) HR seems to have zero problem allowing cis faculty/staff use shortened versions of their names, their middle names, or even a gd nickname––but with trans people, they act like they’re making an unbearable accommodation. [13] For more on such rhetorical situations, I appreciate Dean Spade’s (2018) thoughtful consideration of “Pronoun Go-Rounds” and their risks, limitations, and affordances. More so than insisting upon any single “correct” way to go about shifting cultural norms and conversations, trans scholars and advocates urge us to more thoughtful engagement with the terms we us, how we arrive at them, and how they shape our access to shared spaces.

GPat’s 2nd Thread: “Too Many Accommodations” Recently, while teaching a unit on bisexual erasure in my LGBT Studies course, my students and I read an article by Gonzalez, Ramirez, and Galupo (2016) in which they forward the concept of “bisexual marking.” This term, the authors argue, calls attention to the strategies bisexual and pansexual people employ to combat erasure and other forms of microaggressions in a world that can only imagine people as either gay or straight (p. 510). While the term was new to me, the concept itself seemed familiar, given how often my pansexual orientation has caused discomfort for monosexual folks. But that wasn’t the only reason the term stuck with me.

Figure 7: Image from GPat's Twitter profile. As a person who has been “sirred” and “ma’amed” far more often than I’ve been “mixtered,” I constantly find myself engaged in supplemental forms of communication—textual, digital, and symbolic—in order to be recognized (both interpersonally and institutionally) as a nonbinary trans person. To highlight the additional labor of fighting to be acknowledged in a settler-colonialist culture that insists people are only ever men or women, I forward the concept of nonbinary marking. Lest this concept be understood in the rosy terms of “visibility,” it feels important to emphasize that there are, sometimes, steep consequences to (insisting on) being recognized. Indeed, not all forms of nonbinary marking are equal, and some trans rhetorical tactics are tolerated more than others. The subtle commonplace ways nonbinary people assert their gender, through implicit nonbinary marking, seems to be preferred in the workplace. Such tactics tend to be preferred because (1) they can be ignored, (2) the labor of communicating one’s gender identity falls squarely on the shoulders of nonbinary people, and (3) most importantly, they compel no real response from individuals or institutions.[14] In my professional life, I engage in implicit nonbinary marking in a number of ways: I include my pronouns in the signature of my university email, along with a helpful hyperlink to FAQs about nonbinary genders. I include my pronouns in every publication and professional bio. On my social media accounts, where I frequently interact with colleagues and former students, I not only include pronouns in all of my bios but I also frequently share (and sometimes create) content meant to educate people about nonbinary identities and the institutional barriers enbies sometimes face. Finally, in conversations with new colleagues and students, I find a way (early on) to refer to myself in the third person in order to communicate the pronouns I use (e.g. You might be thinking: “What in the heck are they talking about in Assignment 2?”). I also engage in implicit nonbinary marking through “accessorizing” in professional spaces: Like Jo, I decorate my office door with nonbinary insignia—including a very obvious they/them pronoun sticker right under my office name placard. My office decor similarly boasts nonbinary stickers, posters, and pop culture artifacts. In recent years—because people tend to encounter me with such professional accessories on hand—I have also begun to decorate my laptop, planner, and gradebook with stickers that include: they/them pronouns, trans flags, and popular nonbinary animated characters from pop culture (like Stevonnie and Smoky Quartz from Cartoon Network’s Steven Universe).

Figure 8: Stickers! This latter strategy of nonbinary marking seems to be particularly effective for Gen Z students, who tend to notice my laptop/gradebook stickers with far greater frequency than they notice how I gender myself in class or in my email signature. In fact, I receive about a baker’s dozen of communications per semester (in hallways, in emails, or before/after class) in which students cite one of my enbie-marked accessories as a prompt for seeking clarity on my pronouns, coming out to me as nonbinary, identifying their connection to nonbinary friends, or asking lingering questions about the nuances of gender identity.[15] Alas, these attempts at nonbinary marking are rarely as impactful for my colleagues as they are for my students. In contrast to implicit nonbinary marking, explicit nonbinary marking is a far more risky endeavor, namely because (1) it’s harder to ignore nonbinary people when they’re taking up space but also because (2) it tends to make a direct claim one’s audience, and (3) it often requires actual labor in the form of accountability or solidarity. Whereas implicit nonbinary marking may be disregarded as one colleague’s eccentric whims, explicit nonbinary marking—no matter the circumstances which call for it—tends to be interpreted as unprofessional and uncollegial. Because explicit nonbinary marking tends to surface as a redress to cissexist discrimination or structural inequity, nonbinary people who engage in such tactics—as I will illustrate in my anecdote below—are often understood as line-jumpers who seek “too many accommodations” or as ungrateful supplicants who “take advantage” of their employer’s “generosity.” One of the more notable times I’ve engaged in explicit nonbinary marking began quite on accident, while I was on the job market. I’d been invited for an on-campus interview by a research-heavy Catholic university. Beyond a momentary experience of surprised delight, I hadn’t given a second thought when the search chair asked for my pronouns along with a phonetic spelling of my name and the title of my job talk. Then, on the eve of my interview, I received two calls in succession: The first was from a Wisconsin-based trans group, who wanted to warn me that a well-known conservative professor had published a screed about me on his blog. The second call was from the search committee chair, who offered me vague apologies without ever mentioning the blog in question. Harried, he assured me everything would be fine and to come to campus as scheduled.

|