Vignette 2: Making the Digital Stories Public

In this section, we narrate crucial moments of curation centered on the public dissemination of the completed digital stories:

1. Deciding whether and how to disseminate the digital stories

2. The day of the exhibitionary encounter: Showcasing the stories at the Peace in the Park event (see Figure 1)

Resisting the common participatory impulse to organize around consensus, we demonstrate that participatory curation involves recognizing and navigating tensions that surface in the process (Fine & Torre, 2004; Powell & Takayoshi, 2003).

Deciding whether and how to disseminate the digital stories

As feminist scholars committed to participatory methodologies, we were deliberate in our efforts to foreground youth voices and youth decision making when deciding what to do with the finished products (Fields et. al., 2015; Fox et al., 2010). However, it became evident that the translation of commitment to participatory action is not a straightforward process.

The first moment where the tension became pronounced was at the “Movie Premiere” that we organized for the youth storytellers. This session was a celebratory event where we viewed the finished digital stories and a blooper reel as a group while we enjoyed popcorn and candy. This was followed by individual free-writes, a focus group discussion where youth reflected on the project, and a post-project survey. We had planned to use the focus group to discuss dissemination plans. However, when the youth showed up for the event, they were surprised that we (the university-affiliated researchers) had not invited a larger audience to watch the videos—hence, the exchange we highlight on our introduction page. One of the youth coordinators later revealed that he may have contributed to this misconception, as he prepared the youth in the afterschool group for the upcoming screening (a term we had used interchangeably with the “Movie Premiere”). The misconception was likely further influenced by our choice of terms. We referred to it as a “premiere” and “screening” which, considering the connotations of these terms, may have evoked images of a red carpet-style event.

A critical moment of participatory curation was the moment when we paused, addressed this confusion, and explained that it was “their” video. We emphasized that we could not make unilateral decisions about when and where to show the videos to audiences beyond our group. Our role as participatory action researchers in this moment was to prompt the youth to see themselves as curators for the finished digital stories. In reflecting on the session later, we (Jenna and Urmitapa) discussed the unease brought on by this moment of tension, where we both got the sense that the youth storytellers were either unable to relate to or appreciate our position/decision; or that its significance was not apparently meaningful to them. This tension, in part, speaks to macro cultures and practices where youth are rarely accorded any meaningful voice or decision-making power on issues that concern them. We thus had to contend with the limits of our praxis in the absence of broader structural and cultural shifts.

During the focus group discussion, it became evident that the youth wanted to use the digital stories as a means of critically engaging people on the issues highlighted in the videos. At the same time, there were mixed feelings about the social change potential of these videos, with the youth seemingly hyperaware of the structural barriers to getting an audience at all and getting an audience to engage with the messages (especially school upper-administration).

When we asked youth if they wanted us to arrange a public screening, one participant answered immediately and enthusiastically, “yes!” and other youth murmured agreement. Yet, when we prompted them to consider where to have the screening and who to invite, one participant pivoted to a different idea: “Can we do YouTube?” He explained, “I feel like we would be better, like, to, shown like, from person to person. Like I’d show like, my teacher or something, and then he could probably do all the teachers or something.” Others liked this idea. One young man thought the videos may spread like a “virus” if the YouTube link was shared on social media. Thus, the digital stories are “public” on YouTube, at the request of the storytellers involved, but whether or not this outlet is meaningful for the youth, as co-curators of these collective narratives, is yet to be determined. Our role as facilitators was simply to honor their request to make them public there.

The second moment of tension was in moving forward with the decision to screen the videos during the Peace in the Park event without a clear sense of how the youth storytellers felt about it. Our organizational partners—the youth coordinators—were keen on presenting the videos at the Peace in the Park event. While this made sense for the flow and objectives of their spring programming, we also recognized the possibility that the youth could decide not to show the videos there, or have other ideas about how to disseminate them, and we would have to figure out how to honor those decisions. It was a tension to the extent that we were not privy to processes whereby those decisions were made by the youth storytellers and the youth coordinators since our collaborative engagement with the afterschool program was limited to 11 sessions following which programming was devoted to planning the public event. This “tension” should not be interpreted to mean that youth voice and the coordinators’ roles were mutually exclusive. They were unequivocally invested in youth success and clearly had strong relationships of trust and support with the youth, which were in fact integral to the successful implementation of the digital storytelling project. Thus, while we hoped to honor youth storytellers’ decisions about if, when, and how to disseminate their co-created critical creative work—the digital stories—we also had to respect youth coordinators’ supervisory roles and their curricular plans. This tension draws attention to the ways in which participatory action research involves relinquishing control toward collective purposes, processes and outcomes (Torre & Ayala, 2009).

Although we were not privy to the group process, we caught glimpses of it in the individual interviews that we conducted with the youth storyteller and youth coordinators. As Isabel shared:

We came up with the idea that, "Hey, why don't we show our digital story project." . . . but how are we gonna do it? I said, "Well, we can get laptops. We can borrow from this, and this, this, and that." We talked about it and we figured out a way to do it.

Once the decision to move ahead with the screening at Peace in the Park was made, we helped by creating promotional materials (Figure 2) and aided youth in refining and formatting a paper and pencil survey (Figure 3) to elicit audience feedback.

As Andre, one of the youth coordinators, later commented on the process of building the survey:

I think that they [the youth] felt good that they had created it [the audience survey], they had opportunity for some input and feedback back and forth, and felt very comfortable I think because they were so involved in the creating of the survey, they felt very comfortable when it came time to having people looking at the videos and being able to respond. They could clarify something if there was something unclear or just even have a conversation about how people responded. . . They worked together on it mostly independently. I came on board and asked them what they had come up with, and they showed it to me, and we went back and forth a little bit on some tweaking, and then sent it to [Jenna]. [Jenna] and Urmi put it into a little bit of a different format, but really the same.

The day of the “exhibitionary encounter”

We think of the Peace at the Park event as an “exhibitionary encounter,” described by Pollock (2011, as cited in Linden & Campbell, 2016) as “the artworks as material objects (but also as images and texts), the space of their arrangement and the phenomenological encounter with them, the participating visitor, viewer or agent of the encounter, the invitation to the encounter generated by one who has taken responsibility for the assemblage and the institutionalized occasion.” In this case, the youth had taken responsibility for both the assemblage (the set-up, facilitation, surveys) and the institutionalized occasion (the Peace in the Park event).

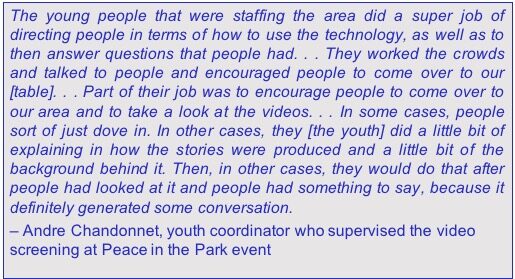

On the day that Peace in the Park was scheduled, we woke up to a very warm and humid day. There were some concerns over rain with an alternative date in case of weather-related cancellation. Fortunately, the weather held after a brief deluge a few hours before the event. The event was held in one of the public parks. A tent was set up for screening the videos. A number of tables from various youth and community-based organizations were set up in a semi-circle with the video tent at one end. Notably, the tables were primarily managed by youth. There were two-three youth at the video tent who were responsible for facilitating the viewings. Two laptops were set up, one with each video and were equipped with earphones. The earphones were especially useful given the music playing in the jukebox. Urmitapa, who was present at the event, remained in the back of the tent or outside it when it was not drizzling. We felt it was important that the youth storytellers were at the forefront. Urmitapa assured the youth of her support if they needed anything but explicitly acknowledged that they (the youth) were “running the show.” And run the show they did (see Fig. 4)!

Figure 4. Excerpt from the transcript of the post-process interview with the youth coordinator

Drawing from audience texts, including observations of the exhibitionary encounter (i.e., interpersonal dialogue) and audience responses to it (i.e., audience feedback surveys) it is clear that showcasing the digital stories at Peace in the Park was not only invitational and propositional but also interventionist in that it served as a locus for critical engagement and action in community settings (Linden & Campbell, 2016; Pollock, 2011, as cited in Linden & Campbell, 2016). See the following slide show for our thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2012) of the audience texts.

Video: Analysis of Audience Texts

[Read More: Reflexive Engagement with Vignette 2]

YOUTH DIGITAL STORYTELLING PROJECT / VIGNETTE 1 / REFLECTION ON VIGNETTE 1/ VIGNETTE 2 / REFLECTION ON VIGNETTE 2 / CONCLUDING REMARKS / REFERENCES