The Last Act of Love: Death and Writing During COVID

Rachel Donegan

Keywords: grandparent death, grief, loss

Categories: Navigating Loss and Grief; Visual, Sonic, Tactile, Interactive Texts as Self- and Collective Care

Content warning: death and grief

|

Figure 1: The last photo of the author and her grandmother, from a wedding in 2019. Her grandmother is wearing a black top with a pink scarf, and she is wearing a green patterned dress. It is a cropped photo from a group picture, and the author is wearing a black eye mask. |

When March 2020 made itself known, I immediately made plans to go home, back to my parents’ home outside of Nashville. The weight of all the unknowns—how to support my students now that the semester was online, how to keep myself safe and healthy, how to keep myself stable while alone in my house—was too much to bear. Out of an abundance of caution, I waited two weeks before making the drive from outside Atlanta. After telling my parents of my plans, I called Granny to check on her and make sure she was actually staying home. Our relationship was a unique one—she was in her 40s when I was born and was a hybrid parent/grandparent in my life. While I was her first grandchild, she eventually had ten others, and proudly claimed that while she wasn’t the kind of Granny who would bake cookies with you, she’d “make sure you got wherever you needed to be on time!” She lived up to her mantra, and often delivered my brother and cousins to and picked us up from every kind of practice imaginable. Since she went to the same church as us, we saw her at least three times a week, often much more. When I went to college and graduate school, I stayed in Middle Tennessee and would go and visit her often. My grandfather had passed away by then, and she loved having people show up at the house. I never needed a reason to come by, and she was one of the few people I could visit without calling first. I liked that. Soon after I got a job in Georgia and moved away, she told me, “Honey, you just go ahead and call me any time you want!” She knew it would be difficult for me to leave, alone, and she was right. |

The next few months were a strange blend of Georgia Life and Tennessee Life: I was still teaching and having meetings, but they were all happening in the dining room of my parents’ house. I would answer emails and make Skype calls with students in the morning and bake bread in the afternoon. Most of my students were just worried about life, about COVID, about how to keep going with classes, and needed someone to talk to. I started knitting a COVID blanket made from fragments of all my past knitting projects, and my mom would text Granny pictures as it got longer and longer. Days soon drifted into weeks, and suddenly it was April. As Easter drew closer, my mom and I strategized on how to get Granny to understand that we couldn’t possibly have Easter dinner this year. To soften the blow, we made cookies and I carefully iced them: lambs, eggs, and hearts with pastel royal icing. When I brought Granny her cookies, we sat outside on her patio instead of around the kitchen table. It was one of those rare, true spring days in Tennessee, with a brilliant, cloudless sky, the kind you have to savor before the oppressive summer heat and humidity takes over.

Looking back, it was one of the last remaining fragments of normal.

By late July, Granny’s congestive heart failure had rapidly gotten worse, to the point where she was done with hospitals and treatments that merely prolonged the inevitable. Congestive heart failure is a disease of attrition, a long, slow slog, and Granny just couldn’t bear it anymore. My mother, a nurse and the Responsible Oldest Daughter, contacted Granny’s doctor for a referral to hospice care at home, and everything was nearly set up by the time Granny left the hospital. She, my aunts, and my cousin, another nurse, set up a rotation where one of them would be with her every night. I went to the house every day. To be honest, I wasn’t sure what I would actually do all day at the house, but I knew I had to be there. I quickly went and pulled the breaks on everything I had going on: podcast interviews, two publications, student orientation, meetings. None of it mattered anymore. When the amount of time you have with someone is down to a few days, anything and everything else feels pointless. Any concern I had about adding to my CV or tenure and promotion vanished. I just didn’t care about any of it. All the while, COVID was a wolf at the door, a massive thunderstorm rumbling in the distance.

Every time I drove home from Granny’s house that week, I prayed over and over that we could be spared from COVID right now, that we could not possibly handle a pandemic and losing Granny all at once. It was a prayer that got answered.

Honestly, the biggest contributions I made that week were to simply sit in the living room with Granny and talk to her. At first, I felt like I was doing nothing—sitting on a couch paled in comparison to the more practical, medical, and physical carework my mother, cousin, and aunts did—but I soon realized that no one else knew what to talk to her about. You can only talk about medication and power of attorney so many times. Our small care group had one rule over that last week: we don’t make dying and leaving us hard on Granny. No blubbering, no “I wish you weren’t dying,” no hysterics in front of her. She was ready to go, and we were not to make her feel bad or guilty for a moment. There were several times where I had to step into the front room or kitchen and just quietly cry for a few minutes, wipe my eyes, and then go right back to sitting with Granny again. Granny’s house was full of food people had dropped off, and a few, small groups of friends stopped by to see us, to see her. There wasn’t much else that needed doing.

|

Figure 2: A close-up of the author's blanket, which is unfinished at the time of writing. The colors shift from gold, grey, gold, grey, maroon, tan, green, deep blue, light blue, to black.

|

I decided to treat my visits that last week exactly like all of the hundreds of times I’d shown up to her house just to spend time with her. On those visits, we’d sit around her kitchen table for hours, talking about nothing (“What’s your mother and dad up to today?”) and everything (the story of how she and my grandfather eloped in high school, which, shockingly, no one had asked her about before). My goal was always to find a way to make her laugh before it was time for me to go. I knew it would be too much for me to try and make her laugh that week, but I resolved to take my cues from her and to keep conversation as normal as possible. Some days that felt impossible, but I owed it to her to at least try. Granny and I talked about all sorts of things that week. She wanted daily updates on Willow, the dog I’d adopted back in June, and how training her was going. I brought the blanket I had been knitting with me, and she loved watching me knit, seeing the yarn colors shift from red, to gold to gray. One day I noticed how the gray yarn color matched her hair exactly. After she was gone, I couldn’t go near the basket for months. Friday was the Last Day, the last day we talked and shared a bit of normal. She’d grown so much weaker and napped for much of the day, but I tried to make sure she wasn’t alone unless she wanted to be. A cousin of mine came to see Granny and was visibly shaken afterwards, so I found some old photo albums and shared some stories Granny had told me about her family. It helped. When I went to put the album back, I found a small envelope sandwiched between the stacks of photos. |

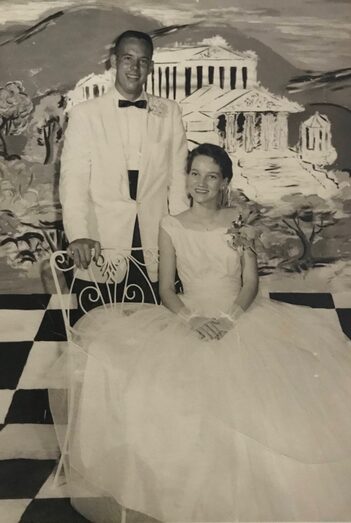

I opened it and discovered an absolute treasure: Granny and Paw Paw (my grandfather)’s prom picture. I couldn’t believe what I found: since they eloped the year before, this was the closest thing to their wedding picture that existed. Granny was awake, so I showed it to her, and her face lit up at the sight of the black and white memory. She told me all about prom night: her dress and gloves were light purple, and her Aunt Christine, who they lived with, lent them her car to use for the night. No one else in the family—not even Mom and her siblings—had ever heard this story or even seen the photo. For years, I’d secretly wished a wedding photo for Granny and Paw Paw existed. A happy marriage like theirs deserved it, and now we had something that was similar. To see this photo of her and Paw Paw young and happy was more than I could have wanted. After seeing the photo, Granny got sad for a moment and worried about what would happen to all her photos after she was gone. I took her hands in mine and promised her I would keep her photos, recipes, and stories, that I would find a way to collect them for everyone. She smiled, and went back to sleep.

|

Figure 3: A black and white photo of the author's grandparents at the 1958 East Nashville High School Prom. Her grandfather is standing and wearing a white tuxedo. Her grandmother is sitting and wearing a pale dress and gloves. They are young and happy.

|

A few months later, I had a print made for Mom’s birthday. We both cried when she opened the package.

Our last conversation that Friday was perfectly ordinary, and we both liked it that way. I was about to leave, because it was my turn to make a grocery run for my parents. A typical Tennessee July thunderstorm was coming, and I wanted to get to the store before it arrived. I gave Granny a big hug, told her I loved her, and that I’d be back in a day or two. As I walked through the kitchen towards the back door, she told me to be safe, and I promised her I would. We said “I love you” one more time, and I left. As I drove up the driveway, pear trees flanking my car, I couldn’t stop crying. Something in me knew it would be the last time.

As the end grew nearer, it soon became clear what my role was in the process—to write. Writing was my biggest single contribution, and it felt so excruciating, so necessary, so awful, so validating. That weekend, Mom asked me to start writing Granny’s obituary. It was a request I saw coming. At first, I blanked a bit on what exactly to include, and Googled “how to write an obituary,” my saddest Google search to date. But I knew Granny well enough to know which relatives to include and which to leave out, as well as the traditional details to include: high school, jobs, family. I knew better than to mention her parents, and put my foot down when I was challenged on it. My heart ached knowing she couldn’t have the service she wanted and deserved. Granny was a woman who lived to help others, who stayed long after church weddings had ended to wash dishes. She was deeply, secretly sentimental, and had a box filled with wedding and graduation programs from her children, grandchildren, and countless others. I put in more details about who she was as a person, how she worked the room and spoke to every single person at weddings, showers, and funerals, how she made everyone feel included. Had COVID not happened, our church would have been packed to the brim with people sharing stories about her larger-than-life personality and her sense of humor. I could have put a slideshow of pictures together. A woman as extroverted and generous as her deserved nothing less, and I couldn’t make it happen. Writing about her was a deeply rooted need, a way to fill the dual losses of her and the ceremonies and moments that help us remember.

As soon as I finished writing the obituary, I decided I wanted to speak at her funeral.

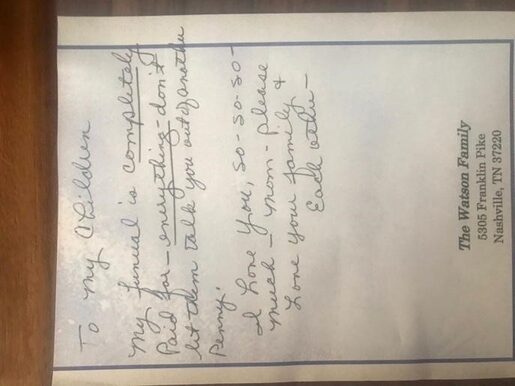

One of Granny’s last acts of love was that she planned and pre-paid for her own funeral. She remembered how stressful, predatory, and horrible it was to plan my grandfather’s service years before, so she had gone to Woodlawn years ago and selected her casket and paid for everything. All we had to do was to call the officiants she picked and choose a few songs. Oh, and make sure we could actually have a service because the second wave of COVID was everywhere.

|

Figure 4: A note the author's grandmother wrote, found after her death: "To my children: My funeral is completely paid for--everything--don't let them talk you out of another penny. I love you so-so-so much--Mom. Please love your family and each other." |

On Monday morning, Mom called from Granny’s house and said she was almost gone. The sky was brilliantly blue that morning, a summertime version of my visit in April. I threw on the closest clothes I could find, grabbed my laptop, and sped across town to her house. In a true Music City Miracle, I hit every green light on the way. Several cars were already at the house when I pulled in the driveway, and I was greeted by a thick, heavy quiet as I entered. My mom, aunts, and uncles surrounded Granny’s hospital bed as her breaths grew shorter and shorter and she drifted in and out of wordless consciousness. I knew I couldn’t speak to her without falling apart, and I didn’t want to make this any harder for her, so I slowly stroked her hair instead. I passed my laptop around the room so everyone could offer feedback on my obituary draft. Some of my cousins made it in time to see her one last time. An hour later, one of Granny’s friends brought some food by the house, and the room emptied to greet and thank her. I stood up and put a photo album back on the shelf. When I turned around, Granny was gone. It was the first time I ever saw someone die. Granny would have hated “all of us sitting around gawking at her,” so her waiting until the room emptied to leave this life was completely within character.

|

The rest of that day was an aching blur—family friends stopping by, all of us praying over Granny’s tiny body, me holding her little feet as I wept. When the funeral home arrived to pick up her body, I hid in the sunroom and begged my dad to keep me from getting up until they had left. While I could handle a lot of what I’d seen that week, I couldn’t bear seeing my beloved Granny loaded into a body bag. My heart couldn’t take it. That night, Mom asked me to help her write a Facebook post announcing Granny’s death, and we found the words to name what felt so impossible. We spent that evening laying in her bed, reading the stories people had shared about her and telling stories of our own. Right before I went to bed, I started writing my eulogy. I started to have doubts over whether or not I had it in me to speak at the service, but I knew I needed to write something. As funeral plans started solidifying, I found my resolve. Even though Granny had planned her service ahead of time, I knew she wouldn’t mind if I spoke. I thought of all the angles I could take for eulogy: sentimental, serious, mournful. But what would have Granny really wanted? For me to make them laugh. So that’s what I did, or at least attempted to do. I wove in funny stories about her unique fashion sense (which consisted largely of hand-me-downs or things her children had left after they married and moved away) in with stories of her generosity, her kindness, her love of her family. The day before her funeral, I started worrying that I didn’t have the right clothes to wear. When I came home back in March, I didn’t know I’d be going to a funeral. But Mom reminded me that Granny, of all people, wouldn’t have cared. |

Figure 5: A photo of the author's grandmother posing before taking a group photo with her friends at an "Old West" themed photo studio in Gatlinburg, Tennessee. She is coyly holding a fan and glancing towards the camera while wearing a blue and gold saloon girl outfit. |

The day of the funeral was overcast and humid. We decided to hold a graveside service so people could actually attend; that, plus local mask mandates, was hopefully enough to keep everyone safe. The funeral home was kind enough to stream the service online as well. We really didn’t know how many people would come, but our corner of the cemetery was packed with camping chairs and people watching from cars, a humbling sight on a hard day. Some of my friends came, and one wondered how I was going to be able to get through the eulogy without falling apart. “I’ll just pretend I’m teaching,” I told her. I made it to the last paragraph before I started crying too hard to continue, and Dad swooped in to finish it for me. Once the funeral ended, I went home. The church had made lunch for us at Granny’s house, but I didn’t want my last memory of eating there to be without her.

Two weeks later, Willow and I went back to Georgia and the fall semester started. I can only remember fragments of that entire semester.

There are still many days where I feel like I’m stuck in July 2020. Grief works like that sometimes, I’ve discovered, ebbing and flowing between feeling numb and drowning in your own tears. It’s been over two years since then, and I still don’t have the time and energy to process it all. How can you wrap your head around your own loss when the pandemic is still raging and so many others have lost loved ones too? I still don’t have an answer. What I do have are seeds of gratitude that, even in the midst of chaos, I didn’t lose sight of what mattered the most, of being present and making the most of the time I had left with Granny. I’ll never regret that.

Bio

Rachel Donegan is now an Assistant Professor of English at Tennessee Technological University, which would have made her Granny very happy. Her research is in disability studies, rhetoric and composition, and accessibility, particularly at the intersections of WPA scholarship and mental disability. Her work has been featured in Writing Spaces and Standing at the Threshold: Working Through Liminality in the Composition and Rhetoric TA Ship.