Snail Mail Love During COVID-19: Building Community and Sustaining Social Kinships in Quarantine

Joanna E. Sanchez-Avila

Keywords: graduate student; disability; snail mail, Honduran-American, Central American

Categories: Visual, Sonic, Tactile, Interactive Texts as Self- and Collective Care; Transnationalism and Inhabiting Borderlands During the Pandemic; BIPOC Perspectives on Labor and Love during COVID; Somewhere in Between: Grad Student Perspectives

Figure 1. Ghost Love.

I am a Honduran-American graduate student living and working in the Southwest, specifically in the occupied lands of the Tohono O’odham and Pascua Yaqui.[1] Being Central American[2] in the Southwest, let alone Honduran-American has been an isolating experience, yet I still make ways to build community across my and our differences (See Figure 1). I also live with chronic depression, social anxiety, complex-PTSD, and bouts of agoraphobia on top of other health needs. As an introvert-extrovert the pre-pandemic life taught me how to balance socializing across diverse contexts. During the wild year of 2020, my snail mail writing became my best and most consistent writing practice and carework. Snail mail, writing letters and sending them out through postal services, like the United States Postal Service (USPS) became forms of building community and sustaining my social relationships during quarantine.

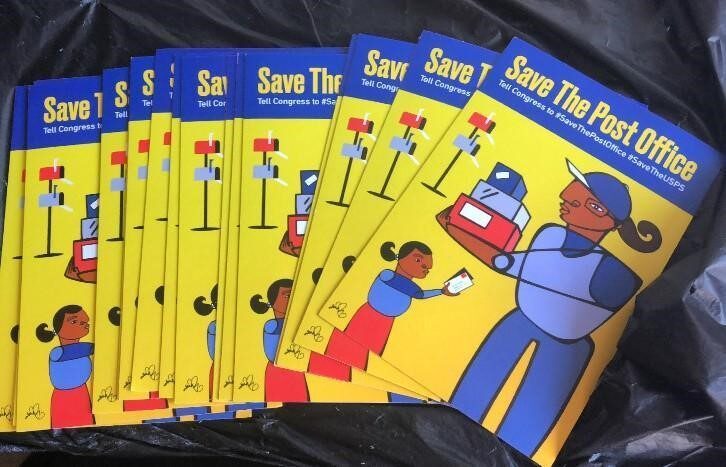

Figure 2. #SaveThePostOffice Postcards by Favianna Rodriguez May 2020.

In 2020, snail mail was not just a resource for staying in touch with loved ones for me, it also became a political civic investment. The United States Postal Service (USPS) became a site of struggle around issues of voting-by-ballot related to voter suppression, federal funding woes due to COVID, limited staffing, and natural disasters caused by the ongoing global climate crisis. These factors and circumstances led to many mail delays nationwide and globally[3] further adding to the ongoing chaos many of us were witnessing. Despite these structural issues, I was still motivated to use USPS’s services and practice writing by producing more intimate forms of communication. Fueled by my love for writing personal notes to others, funds from my humble graduate student budget made their way to support the USPS the best way I could, by buying stamps or postcards and sending snail mail (See Figure 2 & #SaveUSPS).[4]

Participating in a political moment, when I felt powerless and overwhelmed by the competing gradual stressors of my personal life and that of the world, empowered me to stay hopeful and engaged. Writing letters for individuals versus group audiences was a way to slow down how I processed, and hopefully, how we could collectively process the multiplicity of traumas that many of us were personally experiencing and/or witnessing. Simultaneously, snail mail offered us a moment to concretely reflect, share, celebrate, and document our resilience and joys during such difficult times.

Figure 3. Author Masked Selfie.

These macro-issues that were happening with the USPS became opportunities of micro-empowerment for someone like me whose anxiety around all the things that were happening created feelings of helplessness. Watching the daily rises in COVID cases globally, and locally in Pima County added more to the severity of my developing panic of being outside. Also living under police-state mandated curfews added more to my hopelessness. For example, in the Southwest town[5] that I live in, we had state-mandated curfews for a week between 8:00 P.M. to 5:00 A.M. With all these restrictions in place, writing letters and sending care packages to my pen pals and family motivated me to stay in touch with them, but also go outside more often within the confines of our new reality. As my episodes of agoraphobia were gaining intensity, I made taking a trip to my local post office an exciting experience rather than a daunting one. I found joy in riding my bike, taking the bus, or walking over to drop off snail mail because it was a chance to be a fashionista and sport my handmade cloth masks, personally made or gifted to me via snail mail (See Figure 3). Furthermore, it opened lines of communication to talk with pen pals about politics and its impact on our daily lives during an already globally uncertain time.

Simultaneously, I also had to cope with accepting that my loved ones’ jobs in California transitioned them into essential workers. One of my sisters works in hospital settings as a laboratory technician, while the other works at recreation centers with children. Our mom is self-employed in an ice cream truck, and her partner is a delivery/mover with no opportunity to benefit from unemployment or other fiscal resources. Their circumstances also weighed heavily en mi corazón.

Figure 4. “Trump is KILLING U.S.” sign.

The politicized manner of circulating information through the epistolary, or letter writing, genre became a practice of personal and collective reflection and connection across borders, circumstances, and anxieties about the future. In our correspondences, between family and friends, many of us shared how the quarantine was impacting us, from losing our jobs, to working more hours to providing services and carework to other people and/or their children. My pen pals and I texted each other public political art that we saw when we were out and about (See Figure 4). These outdoor findings sometimes gave us talking points to reflect upon in our letters. Sometimes we talked about how we too could show up and voice our concerns on a macroscale or what creative outlets we were enacting at home and/or at work to cope. The emotional, physical, spiritual, and intellectual work of bearing witness to the immediate impacts of the coronavirus, 45 (Trump) administration’s agitating fascism, and the summer social uprisings for Black Lives Matter, refugees, and migrants especially ‘children in cages,’ and the global climate crisis felt too urgent to even make time to serve the academy.

Figure 5. Collage of political postcards by artivist organizations Just Seeds, Amplifier, and Dignidad Rebelde.

I was barely able to grieve my own personal trials and tribulations while witnessing the world literally burn and so much chaos and death amassing every week. As I became more and more involved in writing letters, my academic writing for my dissertation or publication opportunities took a back seat. Most times I found myself collecting political postcards or supporting artivist (art + activism) organization’s fundraisers by purchasing postcards or stickers that I would later send versus focusing on my graduate school writing expectations (See Figure 5).

In 2020, I was expected to develop my dissertation proposal and to get it approved in the spring semester. After multiple life detours that caused long hiatuses of writing, and the growing fears of my PhD funding running out, I was motivated to get it done by the end of summer. By August 2020, I presented my dissertation proposal, or prospectus, passed then was expected to write dissertation chapters, one per month. Even though the blueprint for my last task to earn my PhD designation was manifested; I couldn’t focus on following through with the baby steps to get me to a dissertation defense date. There were multiple personal circumstances that kept me distracted from exclusively focusing on my doctoral writing.

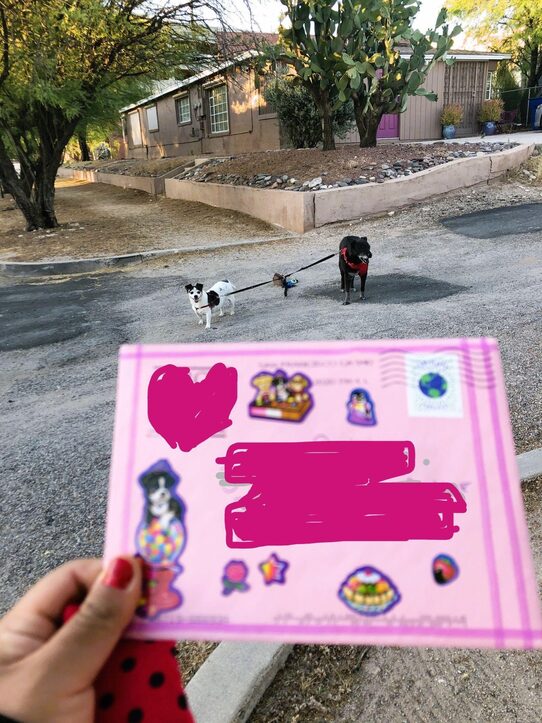

Figure 6. François and Snickers with snail mail.

In the Southwest, I am the primary caregiver to two senior dogs François and Snickers (See Figure 6). At the time, François was a 10-year-old, who had contracted valley fever.[6] Valley fever is a prevalent upper respiratory fungal infection common in the Southwest amongst humans and canines alike that can make someone very ill or can even lead to death. His loud coughing, wheezing, and weight loss was so hard to bear witness to. It was difficult to get restful sleep, let alone feel financially stable to take him to seek urgent veterinary care services and diagnostics. I could empathize with François because between 2016-2017, I had valley fever too. This fungal infection scarred one of my lungs and gave me pneumonia. It took me almost two years to fully recover from it. Having survived valley fever and preparing for the difficulty that lay ahead, with the help of a few friends who were also dog-parents, and my family we were able to find the necessary treatment and healthcare for François.

Additionally, around the same time that François was sick, my other dog Snickers was diagnosed with potential cancer. This news about my Snickers’ health hit close to home because she has been my companion since I was a teenager, and at the time, I was not ready to lose my 14-year-old bond with her through cancer. These urgent calls for carework for my fur children became priority over any personal and professional goals or selfcare. Furthermore, they also triggered my anxious behaviors such as procrastination and avoidance of my dissertation work. I turned to creativity and art therapy as a form to soothe the impacts of gradual stressors that were piling up in my personal life.

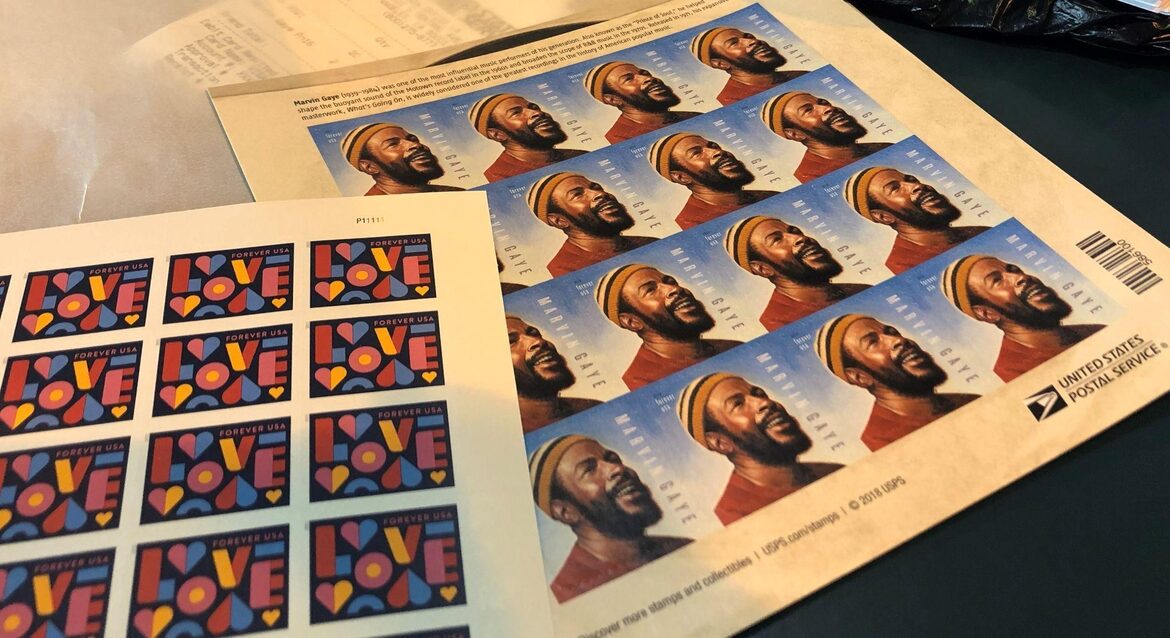

Figure 7. USPS Forever Stamps.

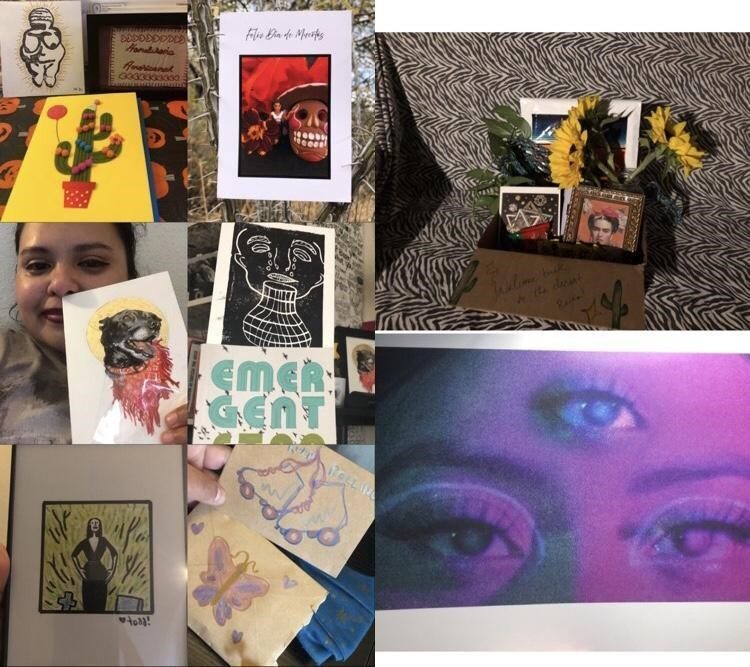

Figure 8. Snail Mail Art Collage.

The carework I provided for my folks relied on creativity as a driving force. The snail mail I send out has a unique flair from the premade postcard designs to the added hand drawn/decorative art on the envelope, to the stamp designs that I use (See Figure 7 & Figure 8). The emotional labor that came with devoting time to send snail mail is part of a practice in cultural curation and multimodal artistic skills that I call, Darkz Tía aesthetics.[7] For example, snail mail writing motivates me to revisit my personal archives of acquired mementos and share them with my social kin.

An affect/effect of personal writing practices such as snail mail is creating intimacies with people long distance through personalized writing. For example, making time to write brief words of affirmation to send out as reminders to family and friends is a practice in gratitude and mindfulness, which highlights one of my favorite long-term effects of snail mail. These letters and postcards were cosechas of mutual carework between my social kin and me. For example, I received care in multiple ways which included having local unexpected friends drop off food and other nourishing goods at my apartment. When François was sick, local folks offered us car rides to veterinarian appointments since throughout graduate school I have relied on public transportation and my bike to mobilize. For my mental health, I was offered socially distant hiking or walking sessions, dinners, or movies.

Some of my pen pals responded back to me not with snail mail but with text messages, or audio messages either via texting or on Instagram’s (IG) Direct Message (DM) feature. And others posted confirmation of receiving their snail mail from me on IG’s Stories feature by tagging me. It was super cool to be in touch with folks multimodally through both analog and digital means of communication. Also, it’s always fun to think about the globalization of messages and the way they travel and circulate. Lastly, writing letters provided moments to reflect upon how ephemera and mementos serve as reminders of people’s investments in each other across borders and distances.

Figure 9. Collage of received snail mail goodies and care packages.

Furthermore, it also provided moments of convergence between being social across multimodal platforms and developing patience within such domains in how I showed up for myself, family, and my social kin. My carework practices did not need to continue adding the instant gratification and information overload that social media cultivates. Social media platforms such as IG became a contentious site of escapism and information overload. Simultaneously, IG was also the space where I grew closer to long distance friends. I was able to see folks’ personal life updates as photo or video posts on their profiles or Stories. IG also became my information hub with snippets of news and mutual aid calls. Most importantly it served as my source for memes.

Some of my online friends call me the ‘Queen of Memes’, since I tend to post a variety of memes on my Stories that exhibit humor, critical education, and reliable information about trending topics. Curating memes is another way that I uplift my social relations in times of need. Despite these positive effects for others and at times myself, it also flared up my mental health symptoms. Emotionally feeling the limitations of Instagram, I turned to snail mail to contain how much energy I put outwards for others.

Figure 10. Author selfie holding 5 letters and packages.

As a doctoral student, let alone All But Dissertation (ABD), writing should be a religious practice. Call me a heathen because I took a detour and redirected my attention to other things during a global pandemic. I turned to art and community to find a sense of meaning and purpose during such turbulent times. Generally, writing letters and sending snail mail are my intuitive gestures of love and generosity. During the onset of the pandemic in 2020 and even now, they were forms of helping myself and my communities find a sense of clarity in the opaqueness that the COVID-19 pandemic intensified. Furthermore, it was a way of staying connected to the network of my social constellations. Carework for me was about reminding folks that someone was thinking about them and expressing that through snail mail. Mi corazón led my hand to paper/postcards/stickers to transmit love close and afar. At the end of the day, visiting the mailbox and finding snail mail from a pen pal beats opening bills any day! May writing letters and sending snail mail be an ongoing practice of generous love as we build and maintain social kinships.

Acknowledgements

With deep gratitude and love, I dedicate this photo-essay to all my snail mail kin, past and present: Roxanna I. Sanchez-Avila, my Fam the Do-Curtin: Tom, Kit, Eva, and Daniel; Margarita Garcia Villa, Marissa M. Juarez, Sarita Gonzales, Guadalupe ‘Lupe’ Guerrero, Rebecca Recinos, Susana N. Ramírez, Iris Alatorre, Monica Contreras, Vani Kannan, Aja Y. Martinez, CHOULi Vision (Reeb Menjivar), Alejandra Ruiz (Lady Ali), Monique Davila, Alyssa Contreras, Sophia Mayorga, Ruben Zecena, Angie Rata y Louie Galvez, Angelia Gionne, Maggie Melo, Antonnet Johnson, Sonia Arellano, Lizeth Zepeda, Nadia Zepeda, Erika Flores, Audrey Silvestre, Roxanna Menendez, MizSkoden (Emilia), Bernadine Hernández, Vanessa Gallego, Madelyn Palowski, Nathania Garcia, Joanna Nuñez, Brytnee Miller, and the many more who sent their love in other ways. I would also like to thank my former and current graduate writing groups for their careful and generous feedback: Dr. Andrea Hernandez Holm, Susana Sepulveda, Jennifer ‘Jen’ Glass, Judith Salcido, and Carmella Scorcia Pacheco. Of course, thank you greatly to the editors of this special issue Drs. Vyshali Manivannan, Ruth Osorio and Jessie Male.

_________________________________________

[1] Learn more about the Pascua Yaqui and Tohono O’odham tribes of Southern Arizona: https://radio.azpm.org/p/radio-buzz/2019/11/15/161748-yaqui-oodham-history-and-sovereignty-in-the-borderlands/

[2] Central Americans in the United States: https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/central-american-immigrants-united-states

[3] Learn more about the “2020 USPS Crisis”: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2020_United_States_Postal_Service_crisis

[4] The Atlantic: https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2020/04/why-postal-service-worth-saving/610672/

[5] Arizona Emergency Declaration, Curfew in Place: https://azgovernor.gov/governor/news/2020/05/emergency-declaration-curfew-place

[6] To learn more about valley fever, visit the Valley Fever Center for Excellence website: https://vfce.arizona.edu/valley-fever-dogs/symptoms

[7] Darkz Ethos is a framework that enacts “goth” subcultural aesthetics rooted in hood politics from South Central Los Angeles, California. Therefore, Darkz Tía aesthetics is a social carework role that I enact when I establish kinship with others while performing tía, or aunty, roles as perceived in Latin American contexts.

Bio

Joanna E. Sanchez-Avila, ella/she, is a Hondureña-Americanah / Honduran-American from South Central Los Angeles, California. She sees the merit in storytelling across different genres and forms. She values the radical potential of narrating both our individual and collective life experiences, therefore, investing her expertise in creating tools and resources for people to tell their stories across multimodal domains (written, verbal, visual, somatic). As a PhD Candidate in Rhetoric, Composition, and the Teaching of English (RCTE) at the University of Arizona, she examines how Hondurans and Honduran-Americans create, produce, and enact their identities transnationally through multimodal forms and practices of remembering (i.e., food, music, poetry, life writing, and photography).