Transnational Carework in the Time of COVID-19

Alex Way

Keywords: parenting; transnational scholar; visa; temporary disability; transnational family

Categories: Transnationalism and Inhabiting Borderlands During the Pandemic; Disability, Illness, and Survival (When the World Doesn’t Want You To); Somewhere in Between: Grad Student Perspectives

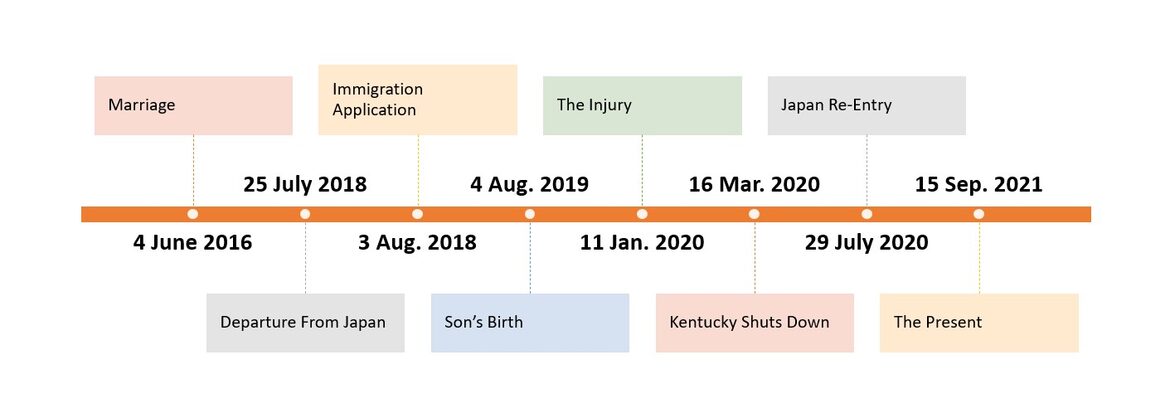

Figure 1. Timeline of the major events in this narrative.

In the months leading up to COVID-19, as well as during the pandemic itself, graduate school would prove challenging due to the demands of transnational carework, as well as my (newly) limited mobility. The following narrative will demonstrate how three overlapping experiences in the past three years—my family’s immigration, my son’s birth, and my ankle injury—became entangled with COVID-19 to impact not only my writing for graduate school, both also the carework I received and was delayed in providing to others.

Immigration

Figure 2. Picture of my passport with two stamps on the visa's page. One stamp reveals that I departed from Narita Airport on January 5, 2020, while the other stamp reveals that I arrived in Haneda Airport on July 29, 2020.

I have a transnational marriage; my wife is from Japan, and I am from Utah. We got married in Japan in 2016 after having known each other for nearly a decade. A couple years following our marriage, I moved back to the United States, alone at the time, to start my PhD program, and my wife was supposed to follow soon behind.

I submitted my wife’s immigration papers as soon as I had established an address in Kentucky. However, due to an overwhelmed immigration system and exclusionary immigration policies under former President Trump and his interference with the United States Customs and Immigration Services (USCIS) agency, the process would become onerously slow. We had to wait a great deal of time for someone to even look at our application. My wife and I figured we would be done within the typical one-year timeline for spousal visas, and we planned an additional member to our family accordingly. But a year had passed, and one month before my son came due in August 2019–and one year since I began the immigration process)—I finally received the notification that my documents were received and being processed. It was welcome progress, but I was frustrated we had not moved further along.

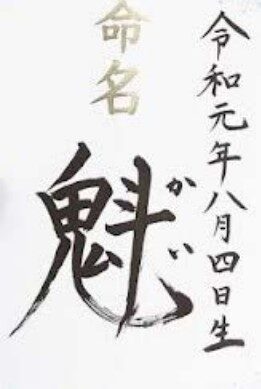

The Birth of 魁

Figure 3. Picture of a name board which states that my son 魁 was born on August 4, 2019. My wife wrote the name and date in Japanese calligraphy.

My son 魁 was born on the morning of August 4, 2019, in Kanazawa, Japan. After five days in the hospital, which is typical for Japanese births, mother and child came home. It was stressful hearing our baby cry throughout the day, and we constantly worried about whether he was eating enough; but he was healthy and perfect, and he was ours. We would be responsible for every aspect of his well-being. Days spent in stress and joy were punctuated by panic due to the quickly approaching semester. Coursework and teaching beckoned. But thankfully, I was able to spend these busy first few weeks with 魁 and my wife before going back to university to begin the fall semester—faculty and administration were understanding of my situation, and they granted me extra time to be with my young family in Japan. However, the time came for me to leave Japan and go back to work in the States. We all cried, and I waved goodbye to my wife and 魁 as my airplane took off from Komatsu Airport.

After returning to the US, I would feel pangs of guilt about not being able to spend time with my family. I relied upon my wife and in-laws to take care of 魁 in my absence. Thankfully, my wife would receive an entire year of maternity and childcare leave. I was also able to see and talk to 魁 for hours every day through FaceTime. Thank god for modern technology. In the year following 魁 ’s birth, we experienced missteps with our paperwork (as well as a pandemic that had unexpectedly swept the world—more on that later). I could not have chosen a worse time for immigration. I could not be physically present for much of the beginning of my son’s life, and it is a void inside me that will never be filled. But I will always be grateful for those who took care of both him and my wife during my absence.

The Injury

Figure 4. X-ray of my ankle post-surgery. It reveals that a plate and eight screws are affixed to my ankle.

On January 11, 2020, I went for a run outside my apartment in Louisville. It had been raining, but the weather cleared up, so I thought I would get some exercise in. I ran down a long and gradual hill on the sidewalk at a fast pace, and soon came upon a puddle. Instinctively I jumped over it, but on the other side of the puddle was a thick layer of mud on the concrete. I slipped and landed forcefully on my ankle. I could not feel my extremities, which was probably due to shock, but I knew I must have broken something. Luckily, some kind onlookers who lived at the house I wiped out in front of took care of me and offered to drive me to the hospital, but I ended up declining and took the ambulance instead (which was a torturous decision for any poor grad student to make). I was in bad shape and did not want to make my injury worse or get blood all over these kind strangers’ upholstery.

I got patched up at the hospital emergency room. The ER doctor told me I had a compound fracture in my right ankle, which meant I would be unable to drive or walk for months. I also needed surgery ASAP. The doctor’s words devastated me. I knew my life would become complicated because I resided on the third floor of an apartment with no elevator, and I needed to frequently travel to and from campus. My wife was concerned, but she was thousands of miles away with her hands tied taking care of our five-month-old boy. My parents soon learned about the accident. Out of concern, they booked tickets to Kentucky the next day. This decision meant they had to cancel their planned golf getaway in California. I will always be grateful for the sacrifices they made to help me.

My parents arrived in Kentucky and acted as my caregivers. They cooked for me, drove me to the hospital to get my surgeries done, helped me cover up my cast so I could take a shower, and helped me in so many other ways. My mother stayed with me for an entire month until I could drive again with a boot. The time she spent away from home was hard on her, but I will always be grateful for her sacrifice.

Through the help of friends and family I was able to get by. A friend or my mother would pick me up from university after I finished seminars, and they dropped me off for my various doctor’s appointments. I learned how to clumsily navigate the steps of my apartment building using crutches. On campus I had to find wheelchair ramps, elevators, and handicap restroom stalls. It was so time-consuming, and I developed a deeper understanding of the term crip time. Those months were difficult, and the experience instilled in me a great admiration for those who navigate their entire lives with limited mobility. I was also touched by college students who opened doors for me and helped me in other subtle ways. The experience restored some of my faith in humanity.

My broken ankle also ensured I spent much of my time composing in my apartment alone, or with my mom watching TV in the next room. I was less socially active than before, but in no way completely isolated. My mother left in February after I received the go—ahead to wear a boot and drive. She felt guilty, but in every single way she went above and beyond in taking care of me. And then the pandemic hit.

The Pandemic

Figure 5. Picture of a closed bar in Louisville. The Irish flags and shamrock adorning the building were intended for St. Patrick’s Day celebrations.

Kentucky went into lockdown during my university’s spring break. I remember listening to a radio program leading up to the COVID-19 lockdown—an American man recounts his experience evacuating Wuhan and feeling like an outcast upon returning to the US because everyone was afraid he had COVID-19. Not long after this broadcast, Governor Beshear announced that dining in all restaurants and bars was to cease on March 16th. My university soon announced that all classes would go online, and that our spring break would be extended by a couple of days to give faculty and instructors time to figure out how to make the move online.

Negative thoughts plagued my mind: Now when will my family be able to migrate to the US? Just when I was regaining my mobility, a plague struck. Will anybody I love get sick? Will I get sick? Will anyone I love die? Could I die?

In some sense perhaps I was lucky to have experienced isolation leading up to the shutdown. It gave me practice for what was to come. At the same time, I (along with graduate students everywhere) could not check out books from the library. And we had to figure out how to teach online on the fly. This all occurred during the second half of spring semester, which is a busy time indeed. In terms of recovery, my future rehab sessions were suddenly in danger of being put on hold. I also required further surgeries on my ankle, and news reports of hospital beds filling up with COVID patients loomed in the background. COVID-19 therefore posed a threat to me receiving the care I required.

I managed to survive the semester. It involved countless nights of writing from my bed with my laptop on my stomach. I always had to keep that ankle elevated. Luckily, I was able to eventually get the surgeries and rehabilitation I required. My rehabilitation provider moved facilities to a large location on the outskirts of the city and added extra precautions, such as a limit of one patient in the building at a time. By the end of the semester, I (and countless others) made a COVID migration. Just one day after the first large-scale social justice demonstrations protesting the murders of Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, and countless others, I drove the long journey to Utah due to the infection risk of flights. Ironically, as I was driving across the country on May 29, I received an email stating that my wife’s immigration paperwork had been approved and that we would be awaiting an embassy interview appointment. Of course by that time international travel was forbidden.

I had to get back to Japan to be with my family. Upon returning to Utah, I spent every day searching online to find out whether international flight was even possible. All international travel was deemed level 4, “Do not travel” by the US Department of State. But luckily travel was opened up for those who have family in Japan, and for military personnel. I would finally be able to travel across the pond and reunite with my family, although I would need to spend two weeks in quarantine upon arriving in Japan, and I also would not be able to use public transportation after getting off the plane. But that was okay. I would finally be able to provide the kind of support and care for my family that I had received while being incapacitated in Kentucky. The thought of flying during the pandemic remained risky, but I took all possible precautions and wore my mask. After arriving in Japan, I took a COVID test. Upon learning about my negative result, I exited the airport and quarantined in a Tokyo hotel for one night. I then rented a car and drove six or so hours to my family’s apartment in Ishikawa Prefecture. The next day I dropped off the rental car in Kanazawa City and was forced to travel back to my apartment on foot. Luckily, I had been out of my boot for a couple of months. So, I jogged the 13 miles back to my family’s apartment and served out the rest of my two-week quarantine.

Taking care of my son in Japan and watching him learn to walk, speak, and crack jokes has been the joy of my life. Child care during exams and dissertating while in a foreign country is no joke, and I often find myself trying to squeeze more productivity out of each day by burning the midnight oil. I do not have access to my campus library, and so I have to get electronic copies, request PDF copies of book chapters from the library, and find other workarounds. The time zone is 13 hours ahead of Kentucky, and so it is difficult to coordinate Zoom meetings that align with everyone’s time zones. I have also missed out on various virtual conferences, professionalization events, and other activities that will help me land a career and other opportunities. But in the grand scheme of things, it is a small price to pay. One small blessing I can count is that with all classes being online or hybrid, I have been able to teach from Japan since arriving here. Exhausted as my wife and I may be, the experience of raising 魁 trumps everything else. My wife finished her maternity and childcare leave earlier this year and has rejoined the workforce, so the stress of constantly being around a two-year-old has eased for her, and me as well. It can be nerve-wracking to have a child in nursery school during a pandemic, but all the teachers wear masks. Furthermore, the vaccine rollout is finally in full gear and over one million doses are being administered each day. Despite the negative publicity surrounding the spread of COVID-19 during the Tokyo Olympics and the state of emergency which still remains in place as I type this, Japan’s COVID-19 numbers remain low, and people genuinely want to protect each other from the disease.

Events in my life from the past three years have become entangled with COVID-19 to impact my transnational caregiving orbit in various ways. The already-tortuous immigration process became much more complicated and drawn-out due to COVID-19, and I was unable to provide care for my son. At the same time, my ankle injury brought others, such as friends and family, into my orbit to take care of me. This resulted in my parents traveling from Utah to Kentucky, thereby disrupting their lives. I was oh so lucky to have them around to take care of me. COVID’s impact on immigration initially kept me away from taking care of my son, but oddly enough, it has now allowed me to stay in Japan due to online teaching becoming the norm. And I have felt safer over here than I would in the States. I’m still unsure about when I’ll be able to return to the States with my family. Everything seems like it is in a state of suspension as we await vaccines. And I am unsure about when we will be able to complete our visa interview at the embassy. In the meantime, I continue with my dissertation and professional development. I just received my second vaccine appointment hours before typing this sentence, and I have two deadlines for articles today (including this one and revisions for a collaborative article in a collection). But for now, I am grateful that my family has remained safe from COVID-19 when so many of my friends and family members in the States have fallen ill. I am grateful to all those who took care of my son in my absence. I am also grateful to those who took care of me when I was injured. But most of all, I am grateful to spend time with my 魁 .

Bio

Alex Way is an assistant professor in the Department of Rhetoric and Writing Studies at the University of Utah. He has taught English for Academic Purposes (EAP) at Kanazawa University in Japan, and English Composition at Washington State University and the University of Louisville. Alex’s research interests include the sociolinguistics of writing, translingual and transmodal orientations to composition, and non-alphabetic literacies.