'WHY ARE WE HERE?': PARACHRONISM AS MULTIMODAL RHETORICAL STRATEGY IN GREY’S ANATOMY

Shannon Howard, Auburn University at Montgomery

HTML | PDF

In its twelfth season, Shonda Rhimes’s long-running television drama Grey’s Anatomy opened its new year without the traditional cast. Main characters Derek (Patrick Dempsey) and Christina (Sandra Oh), the two people most connected to the protagonist Meredith Grey (played by Ellen Pompeo), had exited the show in seasons eleven and ten, leaving most fans to wonder what would happen to the remaining cast in terms of storytelling. Entertainment Weekly reported that over 100, 000 fans signed a petition to bring Dempsey’s Derek back to the show, with many of these fans threatening to boycott future seasons. The season twelve premiere “Sledgehammer,” written by Stacy McKee and directed by Kevin McKidd (who also plays Dr. Owen Hunt), addressed this concern explicitly in the opening scene.

At the start Meredith’s voice over accompanies multiple images of her face on flat screen televisions in an empty exam room, looking directly at the camera (us) and explaining why this year is different. Before she speaks, however, voices from the show’s inaugural season echo quietly through this space: in 2004 the viewer took her/his first tour of a similar examining room when the original cast gathered as a group of interns under the tutelage of Chief of Surgery Richard Webber (played by James Pickens Jr.). Webber’s voice echoes lines from that original pilot as we survey the empty room, in the present: “Each of you comes here today hopeful….” Crossfading over this statement, we hear former resident and now attending physician Miranda Bailey (played by Chandra Wilson) say, “I have five rules. Memorize them.” Other voices, more muffled, fade out. The camera then lands on the multiple projections of Meredith’s face on large screens, overlooking the classroom, and she says, “You might be thinking….I’ve been here before. This is familiar. This is old hat. Maybe you’re wondering . . . why are we here? But I promise . . . you’re about to find out that everything has changed.” In this moment Meredith becomes our teacher rather than just our narrator: her direct address to the camera impels us to change perspective despite lingering doubts about the forthcoming events. However, while Meredith stresses that change is the motif of the new season, this episode’s content suggests a different approach based on celebrating and merging the past with the present.

The writers of Grey’s often engage in a seamless overlap of past and present events, sometimes placing moments from the past directly inside the present narrative. Unlike a flashback, the past and present act as layers to each other rather than separate linear units in the history of the narrative. I argue that this phenomenon prompts the resurrection of an outdated word to describe how the writers manipulate time in rhetorical ways. Rarely used today, the term parachronism, originally defined as an “error in chronology,” is similar to the anachronism but works retroactively instead of forwardly. This is all to say that if an anachronism is a clock of standardized time in a Shakespeare play, a thing too futuristic to belong in a narrative set in medieval Scotland (see Macbeth), the parachronism works in the opposite direction, by using a dated reference to amplify the present situation. Science fiction author Samantha Shannon explains, “The key difference is possibility. It is impossible for Marilyn Monroe to realistically turn up in 1984 - she died in 1962. But it is possible for a man to be wearing a ruff or using a quill in 2005 - just not very likely, given how silly he’d look.” A parachronism occurs with the “dialing” of a cell phone (language that invokes the use of an earlier landline model or rotary device), the “winding” of a clock that now uses a digital interface, or the “flipping” of a channel on our television. In other words, as Shannon says, a parachronism is “more of an oddity than an error.” Furthermore, the winding and flipping suggest that parachronism is most effective when stressing its use of material objects, some of which seem displaced in the present. In other words, a parachronism often occurs as a thing or as a reference to a thing rather than as an abstract phenomenon.

The examples of parachronism that follow serve not as evidence of a close reading (read literary reading) of Grey’s as much as they are a rhetorical study of how Rhimes effectively managed viewer expectations. Webber’s line, “Each of you comes here today, hopeful” has now been repurposed to speak to the present audience. In this sense the past and the present become partners in making the narrative engine run smoothly for a skeptical group of fans.

Conceptions of Narrative and Rhetorical Time

No scholarship at this time exists on parachronism, which creates a quandary in terms of situating this argument. The closest relative to parachronism as a scholarly topic is the language associated with the rhetoric of narratives, both print and on screen. Meredith’s voice over echoes Wayne Booth’s commentary in The Rhetoric of Fiction when he analyzes the “manipulation of mood” and how an author might be “commenting directly on the work itself” in order to influence an audience (1983, pp. 201-09). While novels may use written language, particularly the manipulation of verb tenses, to suggest time’s fluidity or disjoints, visual narrative continues to experiment with this same concept through careful editing, spoken dialogue, and the use of dissolves to indicate flashing back or forward. Seymour Chatman explains that in film the “temporal norm” is “scenic” because both story and discourse operate jointly. However, he stresses that “the more a narrative deviates from this norm, the more it highlights time manipulation as a process or artifice, and the more loudly a narrator’s voice sounds in our ears” (1980, p. 223). In this sense, Meredith is both overtly commenting on the show’s past, present, and future while also calling directly attention to time’s progression and its effect on the audience.

Such overt manipulation of narrative in favor of increasing dramatic effect has become the norm more than the exception. Television has been lauded in recent years as entering a “golden age” of content, one in which directors and writers experiment with more sophisticated structures of narrative, editing, and point of view. Jason Mittell, in his study of what he calls “complex television,” dates the beginning of experimentation in the 1970s, while Steven Johnson hails Hill Street Blues, which aired first in 1981, as the prime ancestor of complexity (65). In his work uniting the fields of Rhetoric and Composition and television studies, Bronwyn T. Williams mentions shows from the 1990s like ER, NYPD Blue, and The X-Files as examples of shows that “require attentive and sophisticated rhetorical work to interpret” (58). David Lavery uses different terms than complex narrative to describe the cultural scene of television in the past two decades; his article on “Lost and Long-Term Television Narrative” includes words like flexi-narrative, neo-baroque, and hybrid and Dickensian narrative to characterize today’s shows and their manipulation of time and structure (313-14). His focus on the show Lost illustrates his belief in complex television being most common in the 2000s. Indeed, Lost featured a rare form of time travel in the famous season six “flash sideways,” which suggested an alternate reality was at work even as the main plot advanced.

Narrative acts as a frame for experience and helps identify cause and effect relationships in both fiction and in our own lives; therefore, the frame communicates a particular view of how reality is shaped. In an older collection of essays linking argument to narrative, Douglas Hesse (1989) helpfully explains, “The reader’s perception of causal sequences is crucial to persuasion through emplotment. To say ‘this’ happened as a result of ‘that’ is to supply a relationship between the two, to make a judgement. We perceive a state of affairs and wish to explain how it has come to exist, searching backwards, asking in ‘digressive’ essays, for example, ‘How did the writer get here?” (p. 114). Such processes, he says, are not different from argumentative and rhetorical work. Still, the “why are we here” question, which Meredith states in explicit terms during the introduction to “Sledgehammer,” requires an expanded vocabulary with which to analyze time, one that calls attention to how time may operate in unconventional ways as it frames narrative.

In terms of rhetoric, one way to approach the use of time is to invoke the frequently cited term kairos, which Sharon Crowley and Debra Hawhee characterize as “a situational kind of time,” one that acts as “a ‘window’ of time during which action is most advantageous” (45). While kairos may explain how Webber’s words are reinvented to speak to the disgruntled audience of the twelfth season specifically, the term does not tell the full story of how “Sledgehammer” works to envelop the past. If lack of attention to kairos leads to missed opportunities (Sutton 413-15) or occasions (De Certeau 85), parachronism is less damning, for it allows us to recreate missed opportunities as if they never passed. Indeed, the first use of kairos was a negative one: the term likely first appeared in The Iliad and originally referred to “a vital or lethal part of the body, one that is particularly susceptible to injury” (Sipiora 2). With Homer kairos was associated with matters of loss, mortality, or failed completion (Sipiora 5), and such ideas certainly characterize Derek Shepherd’s death in season eleven, the event that angered most fans.

We might say that emphasizing missed opportunities and occasions is part of what it means to suffer from losing a loved one before the time of their natural death. Therefore, the new season works toward something that heals such matters, something beyond kairos that heals ruptures rather than calling attention to them. As Rhimes told Hollywood Reporter, she wanted season twelve to be “lighter” but also to “recapture the early season banter and bring the fun back to the show.” The idea of recapturing the past had to be done in ways that both reinforced what was successful at the beginning and also helped fans feel comfortable with the present. The use of parachronism makes that possible.

Bakhtin, in his study of the novel, offers one possible precursor to parachronism when he explains that time (during stories of the agricultural age in particular) acts as a perpetual unfolding genesis, where humans and earth move in tandem through specific patterns of growth and regression. In terms of “how did we get here,” his explanation of folkloric time reads as follows: “The passage of time does not destroy or diminish but rather multiplies and increases the quantity of valuable things; where there is but one seed sown, many stalks of grain appear. . . . (207). Here the study of time does not pave the way for the parachronism strictly speaking, but it gestures toward a cumulative effect. On the other hand, Paul Ricoeur, in his work on narrative, stresses that metatemporal moments in the hero’s quest exist, where time has neither been eliminated or adhered to in linear fashion; rather, the hero descends into a primordial space, or world of dreams that remains in tact until it is ruptured and the world of action (and possible death) is restored (185). Neither of these concepts tells the full story of what happens in Grey’s Anatomy.

Instead of focusing on “mutability,” as Crowley and Hawhee do in their discussion of kairos (47), parachronism would have us consider the “always”-ness of scenes, people, and events. While kairos appeals to particularity and specialization, parachronism suggests a holism or suspension of epochal divisions. Because para as prefix denotes going “around,” “beside,” or “beyond,” the message is that time is capable of veering away from linear notions of past, present, and future and instead working around constraints of these traditional divisions. Likewise, the parachronism works differently than the strategy of repetition, too, although it may begin there. H. Porter Abbot explains that the “temporal structure” of a narrative often returns and revisits certain important moments in the story (242). The parachronism works differently than repetition because its rhetorical power is not based in a desire to hammer home any one image or moment throughout different moments in time. Those differences in time do not exist as separate for the parachronism: nothing that “always is” engages in repetition but exists continually.

However, understanding rhetorical devices like parachronism requires a certain kind of work on the viewer’s part. Byron Hawk explains that in today’s world the audience must consider the importance of rhetorical invention when interacting with a text on screen because “invention becomes something neither unconscious nor conscious. It becomes attentive - a way of being-in-the-world, a way of becom-ing - and in a world of hypermedia, it becomes hyper-attentive” (88). As Hesse says, “The rhetorical value of stories, then, is participatory, not logical” because the writer makes the audience “complicit” in the meaning making process (114). In Hawk’s analysis, elements of the past as discovered through memory become “the place of invention” (88). The work of memory also holds significance for the

Grey’s characters in the previous year - Meredith actually comments in voice over, “Funny, isn’t it? How memory works?” when her husband Derek walks out the door for the last time and later suffers fatal injuries (“How to Save a Life”). Likewise, De Certeau characterizes memory as a condition that “mediates spatial transformations” and then produces a “rupture” or “break” in current action (85). This is significant because while the season eleven “How to Save a Life” episode deals in such ruptures and traumatic moments, with the death of Derek echoing and calling to mind previous deaths the protagonist has suffered through, the parachronism in “Sledgehammer” offers healing as it continues to sync past and present in a way that prevents any disturbance of time’s progression. This strategy, as seen particularly through the use of objects like sledgehammers, paper notes, and a Star Wars spacecraft, actively repairs the damage done by the previous year of darkness and death.

Evidence of Parachronism in “Sledgehammer”

Certain tools (or actor props) in Grey’s suggest a seamless blend of past and present and repeatedly echo the work of parachronism as a multimodal rhetorical strategy. To start, we learn that protagonist Meredith Grey has now returned to her childhood home after losing her husband. When she wakes in her mother’s house, she seems uncertain of the future, just as she was twelve seasons prior. We do not see her move from her former home with Derek; instead, the season begins and it is as if she has never left her bedroom. Suddenly, she hears a loud crash and realizes that her sister-in-law, Amelia, has punched a hole in one of the living room walls with a sledgehammer. This sound provides a jolt that reminds the viewer of the changes happening in what we would consider a familiar and comfortable setting.

Figure 1: Sledgehammer (Wikimedia Commons)

The choice of sledgehammer, a tool formerly used by blacksmiths in earlier eras, could hypothetically serve as one of the first instances of a parachronism since its use was more common in earlier centuries. Since a sledgehammer exerts force violently, the rupture of the wall and the hole that results frames the conflict between the two characters.

Throughout the episode Amelia and Meredith clash over the use of the sledgehammer: Meredith claims that she never suggested that she wanted to change the structure of her house, while Amelia asserts that Meredith (although inebriated at the time) had stated definitively that she wanted to tear the wall down. The use of this tool sets the tone for the show’s new season (It is also important to note that Grey’s Anatomy features song titles for its episodes - this one features the 1980s pop song “Sledgehammer” by Peter Gabriel). The presence of Amelia in Meredith’s house reminds us that while Derek may be gone, his sister remains behind, anchoring the past to the present day. Like the sledgehammer itself, Amelia disrupts tranquility at the Grey home in ways that frustrate Meredith, who is adjusting to life as a widow.

However, unlike memory, which, as De Certeau suggests, ruptures the present circumstance through emotional upheaval, the sledgehammer becomes a tool through which change is made manifest physically. De Certeau explains that memory causes a “coup,” a modification of the local order, but in this season, the coup comes in the comedic form of a blunt instrument. Most viewers relate to the idea of a roommate or sibling encroaching upon their space, and Amelia’s literal rupture of the space, however destructive, feels comfortable compared to the violence and memories associated with the past.

However, the parachronism does invoke emotional pain in the Grey’s hospital patient narrative, a common trope used in all seasons to reinforce the value of medical help and the development of characters as they progress from residents to attending physicians. In such cases, trauma is difficult to avoid since the characters are all surgeons, but most of these patient narratives, unlike Derek’s narrative in year eleven, end happily. In “Sledgehammer” two fifteen year old girls, Jess and Aliyah, are admitted to Grey-Sloan Memorial after they suffer extensive injuries when hit by a train. Their motive was to “die together” due to their family’s inability to accept them as a same-sex couple. Jess is afraid of being sent to a fundamentalist camp that attempts conversion of gay youth into straight members of society.

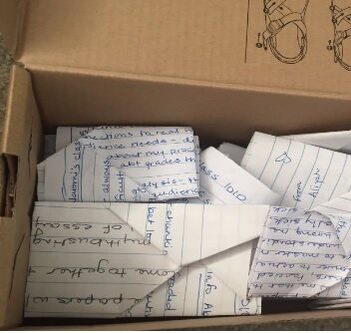

Figure 2: Parachronism - Shoebox of Folded Notes (author’s picture)

Yet, to amplify this kairotic moment, a moment shaped by activism surrounding gay rights and the dangers of such camps, Jess mentions exchanging handwritten letters in secret. The kinds of notes that the two girls describe were most commonly used as 1980s and 1990s communication tools, writings that students passed discreetly among themselves during classes. The folding as a creative way to “mail” or contain such messages calls attention to the tool in a manner that would be hard to duplicate in current exchanges of digital messages. Jess says, “You know Aliyah and I, we like to pass notes at school. The kind that you fold a million different ways. And I kept them. Every single one of them in a box under my bed so I could reread them when I had bad days.” Jess then relates that her mother burned all of these notes in the fireplace when Jess was away. The ephemeral quality of the notebook paper, burning, amplifies this act of Jess’s mother’s betrayal—the contemporary deletion of texts on a cell phone would hardly compete as a similar destructive gesture. The image of a mother burning such handwritten treasures fills the doctors (and also the viewers) with sympathy for the girls, especially since Aliyah must undergo extensive surgery and may not survive.

In this scenario, the idea of the handwritten notes hardly ruptures the fabric of time, yet, as science fiction writer Shannon notes in her explanation of parachronism, it does serve as an “oddity” that might catch our attention differently than a set of texts. The reliance on physical materials to maintain a romance reminds the viewers that loving in itself is a precarious act, subject to erasure. If Derek’s death still hangs over the narrative like a dark shroud, we see that shroud more in the telling of Jess and Aliyah’s story since the injuries from the train crash appear dramatic, just as Derek’s injuries appear in “How to Save a Life.” Still, the notes remind us that the romance is a school-age one, not an adult tragedy, and that Jess and Aliyah still have time to recover. Indeed, by the final scenes of the narrative, both of the girls’ fathers recognize the value of being loved by another, even if such love is less conventional than what they would have initially imagined for their children, and Aliyah’s surgery is a success. The ruptures and traumas of the previous year are avoided.

Those familiar with the Star Wars films may also recognize that the Falcon serves as a parachronism linking the old Star Wars trilogy of the 70s and 80s to J. J. Abrams’s newest installment in the franchise, The Force Awakens, which aired the same year that season twelve began in 2015. In this sense, Bailey speaks to a legacy that is, like the parachronism itself, anchored in the merging of past and present narratives. She also asserts that she is worthy of Chief of Surgery now and always has been. In this sense, she proves Catherine Avery wrong: her ability to invest in the hospital does not make her “too comfortable” but provides her the knowledge to succeed in the position.

Later that night, as Bailey stands on the hospital bridge that overlooks the Seattle landscape, her husband Ben congratulates her for being chosen and then embraces her, gesturing toward the mountains, “Behold - everything the light touches….is yours.” This line, from 1994’s animated film The Lion King, along with the multiple references to Star Wars and the reference to Peter Gabriel’s music with “Sledgehammer,” again suggests the power of past narratives to illumine and color the present action. This appeal also comforts those who felt the Grey’s narrative had focused on trauma too often in the previous year. In both narratives, The Lion King and Star Wars, heroes manage to reclaim their legacy despite the presence of darkness and corrupt leadership. The endings to both films are both overwhelmingly positive for the characters.

Although the parachronism touches on dark themes with the two patients involved in an accident, the use of it still acts as a positive force for the main cast. In this episode Miranda Bailey competes with a visiting surgeon, Tracy McConnell, for the position of Chief of Surgery. While Webber has promised McConnell a hospital tour, Bailey seems put off by her lack of similar treatment, but Webber quickly explains, “You know where everything is.” Even Catherine Avery, the chair of the hospital board, explains that this is the very reason she supports McConnell’s candidacy for chief: “Bailey knows you too well. You’ve been together too long. She doesn’t push you, Richard. . . . I’m saying that she’s too comfortable here. We need someone who will make us uncomfortable. . . . We need someone who will surprise us.” However, while McConnell gives a standard presentation to the board, Bailey counters by asking the board to report to the operating room, where she continues her general surgery while explaining her qualifications to be chief. Her speech is worth quoting at length:

I’m sure Dr. McConnell gave you an excellent presentation. Scissor. [She continues to operate and take tools from her assistants as she speaks.] Watch that tissue. She would be excellent for the job. . . . The point is McConnell and I offer different things. She is new and shiny. And she likes a good challenge. . . . And that’s what this place is to her, her newest challenge. Until she finds her next one. And her next. But that’s not me.

Bailey looks up at the board members while closing the patient’s wound and continues with these words, which, as I will argue, speak directly to the work of the parachronism:

See I don’t care if this place is the shiniest or the fanciest or if it’s a beat up hunk of junk. As far as I’m concerned, it’ll always be the ship that made the Kessel run in less than twelve parsecs. . . .I believe in this hospital and what it can do. And I want to push this bucket of bolts to do the most impossible things you’ve ever seen. And then I’ll do more - because this is my challenge. Clamp. Use the argon beam. Avoid CBD. [She speaks to her surgical team] Slowly. Let me. Good. There. This job was made for me. Staples. This job belongs to me. Suction. I’ve earned first chair. Suture. And every single one of you already knows it. Ready to close.

This speech encapsulates the best of what the parachronism may do as an element of rhetoric: it reminds the audience that the past and the present together are what fuel innovation and future progress. Bailey effectively sets herself up in contrast with the new candidate who tempts the rest of the cast with her “newness” and promises of future success.

Figure 3: Millennium Falcon with action figures from Star Wars (author’s picture)

Most notably, Bailey quotes lines from Star Wars by referencing “this hunk of junk” and its ability to make “the Kessel run in twelve parsecs”: in short, she compares the hospital itself to the Millennium Falcon, Han Solo’s iconic spaceship known for saving the heroes of Star Wars. Here Bailey puts the Falcon front and center rather than regulating it to an outdated pop culture reference. The hospital is the Falcon, now and always, and she is the only one to care for it even when its residents see it only as “a bucket of bolts.”

Conclusion

“Sledgehammer” concludes with the protagonist succumbing to the perverse desire to knock down the wall that Amelia ruined. As the characters hack their way through the plaster and wood, the voice over returns to the topic of change. The camera then cuts between the characters using the sledgehammer and the set of the now filled hospital exam room, the same one that was empty in the opening scene. In the room are new students standing before cadavers. When Meredith walks in, her voice over merges with her physical position, and the message she gives both the new students and the viewers speaks, once again, directly to concerns about season twelve:

So, why are you here? What’s so different? What’s changed? My answer is…you. The thing that has changed is you. I want you to throw everything you think you know about anatomy out the window.... And look at this cadaver like you’ve never seen a human body before. Now pick up your scalpels. Place them below the xiphoid process. Press firmly. No regrets. And let’s begin.

In Meredith’s monologue, she asserts that the world of her hospital is not what changes from season to season; it is the viewer instead who does the growing. This comment has special meaning for those who have spent twelve years with the program, since most people who watch a show for that length have likely gone through different phases in their own lives. As the hammer finally clears a large enough hole in the wall, Meredith and Amelia peer through the opening and smile into the camera. At the same time, a new group of students picks up their scalpels and begins practicing in the lab.

Most long-running television programs continually reinvent themselves in order to impress audience members. Nevertheless, McKee and other writers of Grey’s take a different position by infusing contemporary stories with past allusions and objects. This use of parachronism, a term rarely used today, allows the viewer solace in the old while exploring the present narrative, and such work acts rhetorically to assuage audience fears about a cast existing without its leading man. Parachronism depends on a model of time in which past and present continually envelop each other rather than call attention to their differences. Since Grey’s seeks to recalibrate its tone through capturing the humor of early years, it makes sense that certain objects and ideas from the past would be featured prominently in the season twelve premiere. Still, these objects are not fetishized as vintage tools from past decades but instead seamlessly integrated into 2016 culture. In an age where narratives on screen are continually referred to as remixes, reboots, or remakes, the work of the parachronism remains rhetorical because it appeals to a particular cultural occasion (kairos) while also suspending a strictly linear conception of time. Such rhetorical work, undoubtedly, will remain essential to linking multiple generations of viewers as they consider the cast of a long-running television program to be part of their own history. By giving viewers tangible objects to which they may cling, props such as handwritten notes, spaceships, and sledgehammers anchor the audience in a comforting present while also honoring the tokens of our material past.

References

Abbott, H. P. (2008). The Cambridge introduction to narrative (2nd ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Abrams, N. (2016, May 20). Grey’s anatomy: Ellen Pompeo "disappointed" over fan response to McDreamy’s death. Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved from http://ew.com/article/2016/05/20/greys-anatomy-ellen-pompeo-season-12-interview/

Bakhtin, M. M. (1981). The dialogic imagination: Four essays. (C. Emerson & M. Holquist, Trans.). Austin, TX: University of Texas Press. (Original work published in 1975)

Booth, W. (1983). The rhetoric of fiction (2nd ed.). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Chatman, S. (1980). Story and discourse: Narrative structure in fiction and film. USA: Cornell University Press.

Crowley, S., & Hawhee, D. (2009). Ancient rhetorics for contemporary students (4th ed.). New York, NY: Pearson/Longman.

De Certeau, M. (1988). The practice of everyday life. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Goldberg, L. (2015, August 19). 12 ways Grey’s Anatomy will be different in season 12. The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved from www.hollywoodreporter.com/live-feed/greys-anatomy-season-12-spoilers-816358

Hawk, B. (2003). Hyperrhetoric and the inventive spectator: Remotivating The fifth element. In D. Blakesley (Ed.), The terministic screen: Rhetorical perspectives on film (pp. 70-91). Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press.

Hesse, D. (1989). Persuading as storying: Essays, narrative rhetoric and the college writing course. In R. Andrews (Ed.). Narrative & argument (pp. 106-117). London, UK: Open University Press.

Johnson, S. (2005). Everything bad is good for you: How today’s popular culture is actually making us smarter. New York, NY: Riverhead Books.

Lavery, D. (2009). Lost and long-term television narrative. In P. Harrigan & N. Waldrip-Fruin (Eds.), Third person: Authoring and exploring vast narratives(pp. 313-322). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

McKee, S. (Writer), & McKidd, K. (Director). (2016). Sledgehammer [Television series episode]. In S. Rhimes (Producer), Grey’s anatomy. Retrieved from www.Netflix.com

Mittell, J. (2012-2013). Complex TV: The poetics of contemporary television storytelling (pre-publication ed.). Retrieved from http://mcpress.media-commons.org/complextelevision

Rhimes, S. (Writer), & Hardy, R. (Director). (2016). How to save a life. [Television series episode]. In S. Rhimes (Producer), Grey’s anatomy. Retrieved from www.Netflix.com

Ricoeur, P. (1980). Narrative time. Critical Inquiry, 7(1), 169-90.

Shannon, S. (2013, August 15). Parachronism, possibility, and penny-farthing futurism. Tor.com. Retrieved from www.tor.com/author/samantha-shannon/

Sipiora, P. (2002). Introduction: The ancient concept of kairos. In P. Sipiora & J. S. Baumlin (Eds.), Rhetoric and kairos: Essays in history, theory, and praxis (pp. 1-22). Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Sutton, J. (2001). Kairos. In T. O. Sloane (Ed.), Encyclopedia of rhetoric (pp. 413-417). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Williams, B. T. (2002). Tuned in: Television and the teaching of writing. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.