Book Review

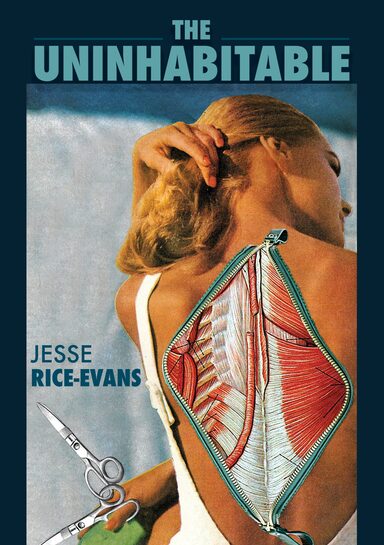

The Uninhabitable

Jesse Rice-Evans

Sibling Rivalry Press, 2019

The Uninhabitable begins with “I have flung my body away from my body” (p. 1). Throughout the chapbook, Jesse Rice-Evans does just that and encourages her readers to do the same. It is difficult to enumerate the exact experience of reading this collection because the language is affective—it causes me to take pause and assess my body as I read and pay more attention to my body as I write.

The collection is divided into 7 parts, each filled with intimate verse concerned with the experience of living in a nonnormative body. Rice-Evan’s passion is palpable as she writes through living in her body. Throughout the chapbook, the author repeatedly brings attention back to her body and all that it is: painfilled, imperfect, female, tough, tender, giving, and joyful.

Rice-Evan’s contribution to the field of rhetoric and composition with this collection is manifold, but particularly in how her poems offer an example of a body’s undoing. These verses conceive of the messiness of bodies—they leak, they spill, they are uncooperative. She writes of her “uncooperative flesh spilling into public space, an occupation” (p. 42). By likening the body’s abjectness to an occupation, Rice-Evans brings attention to the action and movement present within it. These poems force scholars in the field to address the issue already being discussed by many—that the body and its functions are taken for granted within the experience of a normative body.

The nonnormative body, as described by Rice-Evans throughout the book, is not whole or clean but something constantly undone. This undoing and messiness is not presented as a negative, as many normative conceptions of the body would do, but as a complex reality. The chapbook resists normativity through Rice-Evans herself, and her descriptions of her disability, her pain, her queer body and the complicated and ever-shifting way these presentations of her body clash and slip. Even the normative aspects of Rice-Evans body are explicated for a purpose, like “[her] whiteness a neutrality [she] can fade into” (p. 23). The body, within the poems, is not described as any one thing but in terms of the multitudes it contains. It is not only pain but pleasure, not just punishing but also forgiving.

Discussing the materiality of nonnormative bodies is not new in rhetorical studies, as particularly feminist scholars have been bringing attention to the body and the possibilities of writing/reading through it. Cixous says, “Women must write through their bodies, they must invent the impregnable language that will wreck partitions, classes and rhetorics, regulations and codes, they must submerge, cut through, get beyond the ultimate reserve-discourse… the one that, aiming for the impossible, stops short before the word ‘impossible’ and writes it as ‘the end’” (Cixous, 1976, p. 886). The same can be said for people with nonnormative bodies. The experience of living in pain, in a queer body, necessitates the wrecking of discourses that describe the body as whole. Any codes that exist to theorize the body are not sufficient. The field of rhetoric can go farther in how it brings attention to the body, viewing it not just as a material concern, but a modality to write and read through, a nexus of understanding our own ways of existing and agency.

Rice-Evans models this, describing her own body in unfamiliar, yet intimate terms: “If we are anything, we are mismatched” (76). Later, in the same poem, she describes her body in rush of terms, each messier than the last: “I rattle, gush and curl, wrap across your hips and vanish in a web of blood and static, spitting grime and urge” (p. 76). These verses invent their own discourse for discussing the body—one that is spilling out, unique from one moment to the next.

By writing through her body, she opens up channels of embodiment for those lucky enough to read it.

Poetry is a mode that forces the reader to take stock of the body, each line break or punctuation denoting a breath or pause, a place to take stock of both the words on the page and the affective experience of reading. Rice-Evans takes advantage of this form in pieces like “The Necklace”—a poem with long lines and little punctuation, one that leaves the reader breathless.

Reading, then, is not just a process of eyes interpreting text, but in the way a body responds. One of the great contributions this collection makes is in a renewed understanding of what it means to read, that the body cannot be left out of reading.

The Uninhabitable not only brings attention to the body, allowing for the reader to not only examine their own lived experience, but addresses how that experience is communicated linguistically. In many places throughout the chapbook, she undoes notions of a whole body, stating “we are not made whole by pain, no matter what they say. We/ are broken by it, taught to peel back cushion between us and the/ world because we have no choice but to rebuild it, again and again” (p. 30). Communicating the body as not a whole entity, but as something rebuilt consistently, just as it is undone.

The culmination of these affects showcases the powerful potential of writing the body as a modality in and of itself. The nature of reading a text like The Uninhabitable, one that is so aware of the leakiness of the body and its entanglement in every aspect of rhetorical study, illuminates the agency that can live within the body—it is not a passive entity, but can act, communicate, persuade, enact, and resist. Rice-Evans' work shows that the body is a rhetorical entity and that the ways we engage with it during our writing and reading are vital.

It may seem unusual to view a poetry chapbook as a theoretical exemplar, but The Uninhabitable shows the importance of attending to the body. As scholars, the body is so often left out of discussion, or relegated to the works of marginalized people. To echo a sentiment from the “[we] have to think about how [our] bodies will bend or give without emptying” and what it is the emptying can do (p. 15). Much like the experience of reading this work, “To empty feels good,” and is something deeply needed within the field of rhetoric and composition.

—Hannah Taylor, Clemson University

References

Cixous, H. (1976). The laugh of the medusa. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 1(4), 875-893.