Postpartum Fit: Making Space for Feminist Mothering and Mom Bodies in Academic Spaces

Marilee Brooks-Gillies, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis

and

Jessica Jorgenson Borchert, Pittsburg State University

Abstract

Our article discusses how our dress practices have worked to “modify” our bodies as mothers. Eicher (2000) noted how dress practices are actions individuals undertake to modify and supplement the body in order to address physical needs in social spaces. While academic spaces often proclaim “body positivity” out loud (if not in practice), as postpartum academics we sometimes find it hard to embrace body positivity and reconcile the role of mother with our other identity positions. As female Writing Program Administrators (WPAs) of a Writing Center (WC) and a Writing Across the Curriculum (WAC) program respectively, we are keenly aware of our discipline’s “feminized” and “nurturing” identity as something that’s been actively resisted since the feminine is seen as inferior (Grustch McKinney, 2013; Nicholas, 2004). This is particularly true in WCs where “cozy” spaces are cause for distress because “if the writing center is a home and staff is family, that makes the director the mother” (Grutsch McKinney, 2013, p. 26). In other words, presenting as mothers can undermine our identities as serious scholars and administrators. Instead, our article embraces the notion of “feminist mothering” (Miley, 2016; O’Reilly, 2008) and “reclaim our nurturing (mothering) work as empowering, vital work within the institution” (Miley, 2016, p. 2). We contend that the practice of mothering and the bodies of mothers are not impediments to professional spaces and identities. Our article explores the concept of “fit” and examines how our postpartum bodies and our embodied identities and practices as mothers can “fit” in academic spaces. We do not equate our roles as mothers as inferior parts of our identities. We share stories of how we craft our academic personas to negotiate implicit dress codes and embodied norms in academic spaces: sometimes we try to “fit” and other times we stretch the boundaries of those norms recognizing the need for a wider view of what bodies and practices belong in academia.

Rhetoric acknowledges how identities are complex; we all have varying experiences in the ways our identities intersect through race, class, gender, and sexuality. We might see ourselves inhabiting one space—that of an academic professional, for example—whereas we are also inhabiting the space of another—such as a mother to toddlers—as another part of our identity. While we are both writing this article as white, cisgendered, nondisabled, married women, we are also writing from the spaces of remediated and complex identities, such as wife, mother, scholar, professor, and colleague. The blending of identities demonstrates the complexities of selfhoods we experience as academics, partners, and mothers. We see these complexities through the embodiment of motherhood. An example of the embodiment of motherhood exists with the imagery of the pregnant body. The pregnant body is a public, politicized space where the “bump” is viewed as an accessory or a source of social status. While the bump is glamorized, and even seen as social capital, the behaviors of pregnant bodies can be seen as embarrassing because of morning sickness and other physical discomforts. Despite the embarrassing behaviors of pregnant bodies, women have tried to reclaim the pregnant body. For example, the film Labor Pains (2009) demonstrates the social capital of pregnancy when Lindsay Lohan’s character continues to fake a pregnancy because she sees the social attention she receives from looking and acting pregnant. Another example of societal attempts to reclaim the pregnant body exist through how some expectant mothers have shown how pregnancy can be sexy through social media, like how Chrissy Teigen has shown through her Instagram.

Despite genuine efforts to reclaim the pregnant female body, the postpartum body does not hold the same appeal. Postpartum bodies are not viewed as sexy. Postpartum bodies are certainly not glamorized. Most importantly to note, postpartum bodies are not seen as attractive bodies. Even while academic culture capitalizes on the life of the mind, we know that bodies still matter. How we dress for our jobs is noticed by our colleagues and our students. When we faced our postpartum bodies, we discovered clothes that no longer fit and a body that does not seem to match the identities we had so carefully cultivated within our academic spaces. As academic professionals, we have worked against the narrative of the uncomfortable and unattractive postpartum body, often angrily, to create productive spaces for our postpartum bodies within our university cultures, even when we felt discomfort in doing so. The question we ask ourselves as mothers in the academy is simply what does it mean to be a mother in academia? What does it mean to have to get up each day and dress our postpartum bodies?

Postpartum bodies are messy and uncomfortable bodies. To be postpartum in a professional space requires a reframing of identity and dress practices. However, in academia, we do not always like to link issues of dress to identity. After all, bodies may be viewed as “the academy’s dirty secrets” since much of what we do is always seen as being focused on the life of the mind (Cedillo, 2018, p. 2). What is ignored in the life of the mind is that our minds are actually part of our bodies, and how we dress our bodies becomes a way we rhetorically perform our academic personas. After pregnancy, bodies change, and may become unrecognizable versions of the bodies we felt we used to have. The change of our physical bodies after pregnancy may become a permanent situation or at other times the changed postpartum body is a temporary space, something we later shed, like an uncomfortable arrangement. Even as our bodies change (or not) we must learn to develop new rhetorical frameworks and personas to keep on task with the constraints we work within.

Our article examines how our postpartum bodies “fit” within academic spaces. University spaces can be uncomfortable spaces, rife with rules that enforce codes that not all of us are familiar with or accepting of, but are codes we must confront in order to keep our careers (McKinney, 2013; hooks, 1994). In this essay, each of us will share stories of academic motherhood, and how we embody academic spaces and practices on our respective campuses. Each of our stories are different, but within them we each carry thematic threads in the ways we embody academic spaces within our departments, universities, and academic positions. We understand that academic motherhood is messy—we embody multiple relationships of mother, partner, teacher, scholar—and these relationships overlap in ways that are not neat or orderly, as one expects in the role of being seen as a “good mother” (O’Reilly, 2007). Using Andrea O’Reilly, we demonstrate how each of us as writing program administrators practice feminist mothering, or “any practice of mothering that seeks to challenge and change various aspects of patriarchal motherhood that cause mothering to be limited or oppressive to women,” with a particular focus on our own dress practices during postpartum (2007, p. 796). As educators and administrators, we embody a complex, relational practice with other faculty, students, and staff. These relationships with others in and outside of our work spaces sometimes define us in limiting ways—as curators of writing programs or as “den mothers” watching over a “flock” of student employees in a writing center. In reality, our roles are varied, nuanced, and echo what Kinser calls as “relating in multiplicity,” which speaks toward the tension of a mother who has relationships with people other than her children (2008, p. 125). Faculty and students sometimes see us as “nurturers” of the writing their students produce, of the writing assignments they produce, or of the student workers within a writing center. In reality, our roles and relationships are much more complex and our article seeks to create a space of “postpartum fit” within the academic structures we work within each day as we seek to align how our dress practices fit in with the academic roles we embody.

The individual stories we share will not provide easy answers to solving the inherent challenges we encounter in our professional and personal lives as academics and mothers. What we hope to primarily illuminate on are the embodied practices we inhabit as we navigate our academic positions and spaces. In this article we will each focus on our own dress practices as we discuss individual ways we negotiate “fit” in academic culture as mothers, postpartum bodies, and pregnant bodies. Each of us will tell a series of stories that speak toward our past and present embodiments as mothers and as academics. Such stories feel uncomfortable, both for the writer and the reader, so we’d like to remind you and ourselves that “the practice of story doesn’t always feel good, and the stories produced in that practice aren’t always happy celebrations of our community’s accomplishments” (Cultural Rhetorics Theory Lab, 2014, Act II, Scene 3).

Jessica

The month I became Director of Writing Across the Curriculum was the same month I gave birth to my twins, Elise and Alma, at 36 weeks gestation. The appointments were roughly one week apart. On August 10, 2017 I underwent my scheduled c-section to deliver my twins. On August 18, 2017 I was on campus for my first meeting as Director of Writing Across the Curriculum. Since I was only a week postpartum, exhausted from the needs of newborn twins, and recovering from my c-section, I did not understand how attending that meeting would be viewed by others as possibly being a little bananas. I did not have the capacity to understand why other people around me would think that I should probably be at home experiencing my life as a new mother. Even when someone else at the meeting explained it would have been fine if I had not attended, I made a joke about my in-laws taking over my home and needing to be away for a while. This joke was true (my in-laws had taken over my home), but I also felt the meeting was an important one to participate in as our opening department meetings often work to set the tone for the upcoming academic year as we agree to our service commitments and discuss possible teaching assignments for a future semester. But this meeting also sticks with me because it was my first foray into academic motherhood, and the difficulties that are embodied with this practice. The difficulties in this balancing act have, at times, given me to feeling enraged; it is a rage I feel in having to constantly balance my work as a mother and my work as an academic, but this rage has fueled my scholarship. I have written about my experience breastfeeding my twins, and my ultimate failure with breastfeeding (Jorgenson-Borchert, 2019). I’ve presented as part of a panel titled, “Flipping the Career Script: Performing Motherhood Across and Against Traditional Academic Labor Narratives” at #4C19 where I spoke toward my role as a jWPA and mother to twins. One of my particular struggles as a new mother within academic spaces has been through dress practices. During pregnancy and postpartum my body changed, and continues to change, leaving me struggling with finding clothes that fit my body, but also in finding clothes that fits the rhetorical persona, or embodiment, that I wish to represent as an academic professional.

To illustrate my dress practices during my postpartum period, I’ll use a selection of personal photos to give a feminist phenomenological approach to my narrative. These images will illustrate my dress practices as I searched to find my postpartum fit within academic spaces. To be honest, I feel somewhat exposed in showing photos of myself in this way. For one, I’ve never liked photos of myself since I’ve never been seen, or have seen myself as a “worthy” subject for photography (Bourdieu, 1990). I am not particularly beautiful, and frankly, I’ve never been interested in being photographed. In entering academic motherhood, photos became an undeniable part of my personal and professional life. Another reason showing these photos feels uncomfortable is because I look uncomfortable. Many of the photos I took represent the discomfort I was feeling about my body, as my body changed dramatically after giving birth. No longer did I represent, at least in some ways, the standards of beauty for a white woman: visibly thin with smaller, defined features. After giving birth, even two years postpartum, my stomach still bulges out as if parts of the pregnancy have never left.

|

Figure 1: First family photo, 12 August 2017.

The family photograph is an identifiable genre in how its purpose is to provide a compelling narrative of a happy family life. Family photos function creates and manages an appearance of what it means to be a happy family, complete with bodies that look healthy and smiling faces to signify personal happiness. Our first family photo (see Fig. 1) represents the ideal family photograph in some ways, but perhaps not in other ways. In the photo, my partner beams proudly, holding one of our twins, Alma, in his arms. I’m also looking like a new proud parent, but when I look at myself in this photo, I notice how I look pale and exhausted from giving birth via c-section where I encountered complications from blood loss. My face appears puffy. My still swollen postpartum stomach can be seen. Elise is the crying infant in my arms, and at least to me, symbolizes how unprepared I felt to be a mother. I remember as we arranged ourselves for this photo that I could not get Elise to calm down and I kept feeling as if I wasn’t holding her correctly, like I was doing something wrong.

That something wrong followed me beyond that first family photo in the form of breastfeeding. I had decided to try breastfeeding my twins, at least part time breastfeeding, since I continued to work even after the birth of the twins. Breastfeeding turned out to be complicated. My body did not produce much milk, and as to why this was never explained to me. My newborns also had trouble latching, which frustrated both me and the lactation consultant I worked with. I had to use nipple shields in order to get the babies to latch for any real length of time. I kept trying, mostly in vain, to get breastfeeding to work until I went to one of my follow-up appointments and was told by a nurse that babies that were never in the NICU tend to have a harder time with breastfeeding. Much like my newborns, these babies often fell asleep, mostly of exhaustion, in the middle of breastfeeding. No one, not even the lactation consultant, had told me this. I left that appointment feeling defeated, but at the same time a bit relieved as I finally had an explanation about why I felt like I was failing. And since I could finally wean the babies from breastfeeding, I felt I would not be as hungry so often and could start to work off some of the weight I had gained during my twin pregnancy, which was around 40 pounds. Not all of it was weight that left me easily and I probably still carry some of that weight now.

I was not prepared for the ways in which new motherhood and my postpartum body challenged my appearance. Logically, I knew my appearance would change post-birth, but I did not understand that these physical changes would last much longer than just a few weeks or that some changes may be permanent. The changes I noticed at first were the most immediate. My stomach swelling took what felt like months to go down. Clothes no longer fit me, leaving me to continue to wear some of my maternity clothing or oversized t-shirts for over a year after giving birth. I understand that sharing this does not make me unique as a postpartum woman, but my narrative will work to elaborate how my postpartum changes forced me to reshape my dress practices and, in some ways, to reshape my identity from someone who had been seen as thin to someone who is not as thin anymore (think of a pear). Because of how my stomach muscles stretched during my twin pregnancy I have what is commonly called abdominal separation, or diastasis recti, a condition where your stomach muscles are separated leaving a noticeable bulge in my stomach area.

|

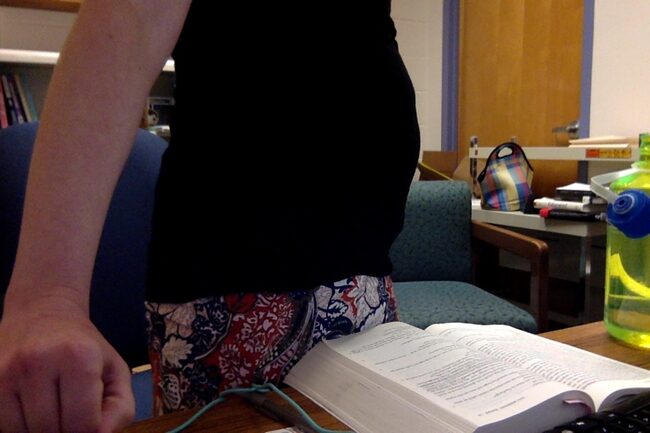

Figure 2: Jessica, 1 month postpartum, September 2017.

To share a visual representation of my postpartum body just a month after giving birth I’ve included a photo of me one month postpartum (see Fig. 2). I remember taking this photo on a day I did not have any scheduled meetings or teaching, but went to the office to get some course planning and administration tasks done. I remember feeling so uncomfortable in the clothes I was wearing to work and feeling so uncomfortable with my postpartum body, and my postpartum identity of mother-scholar, that I felt the need to document that discomfort in some way. Certainly, the image below looks awkward, and perhaps unprofessional to some viewers as I’m wearing a screen print t-shirt and a loose, dark colored skirt that I wore throughout my twin pregnancy.

Looking at myself in my one-month postpartum photo (see Fig. 2) feels embarrassing, even though I know there is a natural explanation for how my body looked at that time. Before pregnancy and birth, I had always been seen as a small, thin person. I took pride in thinness of my identity, and so much so that being thin was a large component of my identity. When I was thin, I was able to purchase and wear clothing that accented my thin body. After giving birth, I spent over a year mourning my previous body. I still mourn that body, though I’ve become a little more accepting of my body than I was in the picture above. I’ve altered my clothing choices by choosing clothing that does not form to my shape but instead flows with my body’s movements. I stress about how a shirt fits against my stomach. I’ll try the same shirt with multiple skirts to see what looks better, what skirt might help to de-emphasize my stomach bulge. I’ve had to get rid of a few of my old shirts since many of them don’t fit me well, instead working to emphasize what could possibly be a pregnant belly on my small frame. In doing all this stressful re-imagining of my body, or what I term “dresswork,” I’ve learned that I just have the body that I have. I cannot hide this body. This body is me and mine and it is still a hard thing to reconcile, but I think I am getting better about learning this is me now.

Postpartum was also a difficult time because my body became a foreign space, a foreign thing I was forced to carry around with me because it was me. Identity became something I had to work to rediscover. In essence, I had to rehome myself through my dress practices so that my body was a space I could identify with again. Feelings of feeling foreign with my own body were not just due to body shape, but because of the added postpartum weight I was carrying. I could physically feel the extra weight with the heaviness in my stomach and the discomfort I felt when I bent over for too long (and still feel, especially after eating, thanks diastasis recti). Because of the extra pounds, and the continued swell of my stomach, I still had to wear the clothes I wore during pregnancy because nothing pre-pregnancy fit my body well and some pre-pregnancy clothes did not fit at all. I also did not have enough money to go out and buy new clothes. Growing up in poverty made the whole concept of buying new clothes when I still had a closet full of clothes seem ridiculous. Growing up in poverty made me think, and still makes me think, that I only really need new clothes if my current clothing is falling apart enough that it cannot be mended. I felt instead my body was a thing that needed to be mended. Along with having very little clothing that fit my postpartum body, I knew I looked pregnant no matter what clothing I put on. For example, I had colleagues who had not realized I had given birth only weeks ago commenting on what they assumed was my pregnant body. In one instance, a white, male graduate student asked me at the start of the 2017 fall semester if I was going to give birth soon. I explained I gave birth earlier that August and in efforts to deflect my own feelings and possibly his, I happily showed a picture of my children. Further, when I showed the above photo of myself at one month postpartum to my younger brother (Fig. 2), he commented how my body “just looks awkward.” Because of the awkward shape my body still had after giving birth, I often wore shapewear that would, with some minimal effect, make my stomach appear smaller as I was tired of explaining to people that I wasn’t pregnant and I was also tired of looking pregnant. Since my pre-pregnancy identity was so strongly tied to being thin, I wanted to recreate the effect of looking thin. The results weren’t always that effective even with the shapewear, however, because I still received questions from well-meaning strangers about “when I was due” even up to nine months after giving birth.

My dress practices continued to evolve as I worked throughout the first nine months after having my twins. Much of my dresswork was focused on ways to de-emphasize my stomach bulge, but considering the conversations I was having with my colleagues these efforts were not working like I had hoped. These conversations often started with something along the lines of “are you expecting?” or “when are you due?” After leaving a meeting at the end of spring semester, a colleague I had been working with closely on an institutional concern stated empathetically to me, “I bet you are tired.” After leaving our conversation, I realized that she thought I was tired because I was pregnant, not because I had twin babies at home. I felt defeated as I left work that day because I always tried so hard to hide my body. A few weeks after the incident with a campus colleague, my university held an academic conference. At the conference I happened to visit with one of the deans who had the nerve to excitedly ask me if I was pregnant. I awkwardly replied I had twins in August, to which he responded that his daughter also had twins and commented on how wonderful it was to be a grandparent. I found the whole exchange embarrassing and isolating because again my postpartum body seemed to be controlling the conversation.

Continuing conversations and comments about my body and dress practices emphasize how when I teach and when I meet with other faculty and higher-level administrators, I’m keenly observed, even before conversation establishing my professional, academic identity begins. Thus, dress practices, or dresswork, in academic spaces matter as dress practices not only shape the body, but give away key parts of one’s professional and personal identity. Visibly looking like a mother did cause me to feel as if, at times, my mothering role was being emphasized over my professional role, such as what happened when that administrator stopped me at the conference to ask if I was pregnant. Past research on how identity is connected to dress practices argues that the “dressed body” is a “basic element of identity and dress choices help create personal narratives (Gonzalez and Bovone 2012, p 67). Eicher (2000) noted how dress practices are actions individuals undertake to modify and supplement the body in order to address physical needs in social spaces. Academic spaces are social spaces that often proclaim “body positivity” out loud (if not in practice), but as postpartum academic mother I found it difficult to embrace body positivity and reconcile the role of mother with my other identity positions as a teacher, administrator, and a colleague. My body had shifted, and with this shift I turned to remediations of my body, which led me to find ways of remixing my postpartum body to my professional practices. While my body gave comfort to my children (breastfeeding, warmth), that same body did not always feel comfortable to me. It was as if my once “comfortable body” had slipped from the former “comfortable chairs” I had previously occupied as an academic (Ahmed, 2017, p. 123). I can relate many instances of times I have stepped into a meeting, only to be greeted by questions about my children or half-jests about sleep deprivation. I understand this is done as a way to create relationships through seemingly innocuous small talk before we discuss the meeting agenda, however I still find it to be a way to stereotype me and feminize my professional identity in a field that is already feminized. When a colleague mentions the fact I’m a mother to a person I don’t know at a professional event, how then do I reclaim an identity built on my academic experience instead of my experience as a mother? These instances are frustrating to me. At this point, I’ve learned to smile, acknowledge the remark, and then mention something about what I do in the professional spaces I occupy in attempts to reposition myself.

|

Figure 3: Jessica, 1 year postpartum, September 2018.

On a day before walking into the classroom, I took a photo of myself when I was over a year postpartum (see Fig. 3). Much like how I wanted to document my discomfort only a year ago, I wanted to document how I had changed and been able to change. I felt confident again. I noticed how not just my body has changed, but I also wanted to use the moment to further document my dresswork. In this photo, I am wearing clothes that I normally wear to work and not an oversized t-shirt and a skirt I had worn when I was 8 months pregnant with twins. At the time I took the photo, I still did not fit into all of my pre-pregnancy clothing (I still don’t), but I was recognizing myself again. Despite looking normal, it was still off-putting to me when colleagues would tell me things like, “I can’t believe you had twins! You are so tiny!” I have no idea what a woman who has a multiple pregnancy is supposed to look like. Even though I looked more like myself again in this photo it’s partly due to the shapewear I was wearing after one year postpartum, and further I certainly wouldn’t describe myself as tiny or incapable of carrying a multiple pregnancy to term. As a 5’4 and relatively thin-ish, my postpartum belly bulge is still visible because of my smaller frame. Even today when I catch myself in the mirror in a side view, I’m still somewhat surprised by how visible my stomach remains. I remember walking home after work one day when I was four months postpartum and having a stranger tell me I had “swallowed a pill that made my belly button poke out.” This comment from a stranger as I walked past made me feel shaken and exposed. I felt so visible. I also remember feeling angry and hurt that a complete stranger to me felt like they had the right or responsibility to comment on my body. I thought about explaining to her I had just given birth a few months ago, but decided instead to keep walking. While I may have physically felt uncomfortable in my own body, the comments from others sometimes felt worse because they reminded me how others were constructing my identity in ways I could not control.

I write this now with some distance as I am no longer postpartum. My twins are two years old. I have learned to see my body as a space that has allowed me to develop a director self, despite how motherhood has also created some limitations. I can no longer always work on research when I want to and so I cannot fulfill the dangerous and idealized stereotype of the 24/7 academic. However, encountering limitations and challenges has made me braver as a person. My mom body has made me braver. Before kids, I would often stay quiet, even in the face of injustice, which probably speaks toward my upper midwest upbringing than it does my personality. After I became pregnant during my first year on the tenure-track, I felt I could not be academically successful or tenured while also staying silent. I begin to focus on finding ways to become a better advocate, both for myself and for others around me who were navigating similar complex spaces within academia. A couple weeks after I found out I was pregnant, I was able to get all my professional and technical writing courses online for my fall semester, after the babies were born. This kindness was extended to me because of our past director of professional writing whose sister had triplets and probably knew better than I did what I was in for. Because our family leave policy mainly protected senior faculty, I worked with my university’s bargaining unit in efforts to improve our family leave policies.[1] The results were less than what I had hoped for, but I was able to start conversations about parental leave, and I’m happy to say these conversations are continuing. As a pre-tenure faculty member, advocating for myself and others among upper administration and senior faculty was a scary thing to do, but these actions helped make me realize being silent was not an effective coping skill. Silence does not create change. I begin to see my new mom body as a brave space and seeing myself in that way made me do brave, challenging work. I continue to advocate for other mother-scholars (and parent-scholars more broadly) within academic spaces. As a writing program administrator overseeing a writing program, I could advocate for the time of instructors who teach our writing-intensive courses, some of whom have children themselves. My advocacy worked to grant a pay raise for all faculty who help with our university writing assessment. Looking back, my postpartum body served as a catalyst for me to become a stronger advocate for myself and others, which was a result I never expected upon entering new motherhood.

As I finish this narrative, in a final moment of reflection, I’ll admit to sometimes feeling angry about motherhood coupled with academic culture. Certainly, I love my children, and I do appreciate everything pregnancy, postpartum, and raising children has taught me. I’ve grown as a person because of my children, but I would have grown as a person without them, too. Sometimes I feel anger over the constant puzzle I have to solve, the constant maze-like daily tasks I go through in order to be a functional academic mother as I research, teach, and care for my twins. While this balancing act is challenging, what angers me most about motherhood is how I feel I have been treated by some other academics around me, from time to time: like I’m inferior, too busy, or just preoccupied to do the work everyone else is doing. All of these assumptions I despise. Becoming a mother while a tenure-track academic did not place me in an inferior position nor did it permanently preoccupy me or keep me in a perpetual state of busy. At times, I may look like I am locked in a perpetual state of busy, but I do find time for me. I’m still keeping up on my Netflix binge-watching after all that has happened in the past two years. I still read books for pleasure. I still sometimes find the opportunity to do nothing. All the same, I do still find it difficult to gather enough energy to hang out with friends after the kids are put to bed, but that is likely due to my introvert nature and not just the exhaustion I feel after a long day between work and parenting. What I want y’all to know is that my mother-self has enriched my scholarship, practices, and pedagogies. Becoming a mother, and giving birth, can be seen as a story of power, not of defeat, not of weakness, and certainly not of giving into patriarchal norms. I feel as if I have created a productive set of best practices for myself as a mother-scholar, as I’ve found the time I need to get my work done, but also have been able to spend valuable time as a parent to my children and a partner to my husband. Part of my truth is that the academy is a patriarchal space that does not always value the risk-taking I took (and still take, as I am writing this, a narrative sharing some personal and painful information) in advocating for myself and others as a jWPA. I continue to see my mom body and all that implies as a brave space. I work to speak toward the rage I have felt—and feel—as I perform within academic spaces that are not always a natural “fit” for mother-scholars.

Marilee

When I first met my colleagues at my current institution, I was 33 weeks pregnant on a campus visit for a tenure-line position as the University Writing Center (UWC) Director. I didn’t tell the search committee about my condition, as I wasn’t sure if it would be used against me despite federal protections. The colleague who picked me up from the airport was unfazed, not indicating any sort of visual response, and we quickly jumped into conversation about my trip. We had a friendly visit to campus, where we were attending a sabbatical talk of another English department colleague. There I met other colleagues, including one who had a much harder time hiding his surprise. His glance went to my (rather gigantic) pregnant belly and then up to my eyes, then back to my pregnant body, and then back to my eyes. I believe this was unintentional, but I thought in that moment, “Well, this might not work out” and chose to find the whole event hilarious. The next morning, a colleague on the search committee slipped and said “congratulations” before covering her mouth with both hands, after remembering, of course, that the topic was out of bounds. My mom body has always been part of my relationships with my institutional colleagues.

I now make myself wonder: from an initial reading of my body and typical dress choices what do observers intuit or assume, consciously or not? The messages my body shares have implications for my work; as Harry Denny (2018) points out, “the politics of identity are legible, material, and felt” (p. 123). What does my body and how I dress it say, and how does that complicate my ability to do the work of academe, and how that work is valued or seen by others, including the work of writing program administration?

Unlike Jessica, I’ve always been outspoken. I speak my mind at most opportunities. My attire, in many ways, matches my outspokenness in that I veer toward the bold and bright when it comes to patterns and colors. Also unlike Jessica, I’ve never been thin. Conventionally attractive female bodies are thin with large breasts. I’m a tall-ish, fat, white, heterosexual, cisgender, nondisabled, middle-aged woman with fine, flat, jaw-length, dishwater blonde hair, small, deep-set green eyes, and a flat chest. I wear glasses but no makeup and almost no jewelry, dress primarily in comfortable, casual dresses, and am known for my collection of colorful flats. I’m quick to emotion, smiling, laughing, blushing, and angering easily. While I attempt to be body positive, my foundational training to believe that fat bodies are not as valuable as other bodies runs deep. I’ve always considered myself heavy, even while wearing the higher-end of regular sizes before gaining seventy pounds during the course of graduate school and two pregnancies which took me into the lower-range of the plus sizes. I sometimes wonder how my conventionally attractive, slim husband finds my body attractive, and until my pregnancies I tried not to think about my physical form in relation to my work often, although I was and am certain it makes an impact on how I am understood and read by my colleagues. That said, my several privileged identity markers make my path through life easier and the readings of my body less dangerous than those without privileged identities.

While I hold several privileged identities, I also have identities that have been historically marginalized. I am a woman, I am a mother, I am fat, I work in the discipline of writing studies, and I am from a working class background. People who inhabit marginalized identities are often pressured to progress beyond them. Some examples: women are asked to perform in ways that are more typically identified with men; mothers are simultaneously told to work full time and aspire to having rewarding careers and encouraged to spend as much time as possible with their children; fat people are told to exercise and eat healthier with the ultimate goal of losing weight; writing studies has worked to legitimate itself in higher education through securing more tenure-track positions; working-class individuals are prompted to go to college and seek middle or professional class jobs. Besides adding a new marginalized identity, motherhood didn’t change any of these realities for me. Motherhood, instead, made me more reflective and thoughtful about my dress choices and reinforced what I already knew—it can be difficult to perform well (i.e. in expected ways) as a woman in academe, to be professional but approachable, to proudly claim my marginalized positionality while trying to pull it out of the margins. Below I share a few stories about how becoming a mother has made me reflect upon my dress practices in ways that have implications for my professional life.

Dressing a Pregnant Body: Adorable and Powerful

Dressing while pregnant was easy and lovely. I was less self-conscious about my flat chest because my baby bump took center stage, and people often remarked about how cute I was. Since pregnancy is temporary, I didn’t overthink my wardrobe. Knowing I’d only wear them a few months, I purchased my maternity clothes secondhand and from affordable retailers, like Old Navy. These clothes often accentuated the notion of being adorable by including a sash to tie around my middle resulting in a bow resting atop my bump. Pregnancy hormones provided my fine hair with a boost, as pregnant women tend to grow hair more quickly and lose less of it.

|

Figure 4: Marilee at 38 weeks pregnant and her son, December 2017.

My morning sickness was limited primarily to the first-trimester and mild. My body didn’t really ache much during my first pregnancy, and I was fairly comfortable until the third trimester of my second pregnancy. During my first pregnancy, I was able to take lots of post-work naps, a rare luxury in my previous life. This meant I was pretty comfortable for a pregnant lady (minus the truly awful and persistent heartburn) and even a little pampered. I looked forward to getting pregnant a second time not just because I wanted another baby but also because I missed wearing my maternity clothes, since nothing seemed to fit my postpartum body. In the picture above (see Fig. 4), I am twelve days away from delivering my daughter, a 9 pound, 3.5 ounce baby. I weigh 265 pounds. I am wearing a maternity sweater and skirt. The outfit isn’t terribly remarkable, but I look adorable anyway because of my baby bump. My 2-year-old son pointing to baby sister in my belly amps up the adorable factor even more. I’m still fat and flat chested but being pregnant meant almost effortless recognition for being cute in a way that is largely understood to be feminine. My dress practices were easy and rewarded.

|

Figure 5: Marilee, 39 weeks pregnant, April 2015.

I didn’t realize how being pregnant and dressing my pregnant body would enable me to reap the benefits of performing as quintessentially feminine and how much I would like it. It wasn’t something I had really even seen as available to me in the past because I always felt my flat chest and fat body made such expressions difficult. Prior to my pregnancies, I didn’t consider dressing in a feminine way a primary factor in my dress choices. Like Scotty Secrist, I needed to reflect on questions like “What do I assume my identity should be because of my body?” (Smith et al., 2017, p. 50). I had placed limitations on the extent to which I could perform as feminine. While pregnant, I began to think about how powerful the female body is. While I was socially and externally rewarded pretty much for just having a pregnant body, I also found internal gratification in my pregnant body and confidence in dressing it and moving in it. Once again my usual frustrations with my flat chest and fat body and the difficulty I had dressing them were less important because I could carry a baby in this body anyway. I could perform as quintessentially female despite those features. I could grow a person inside my body, and that’s amazing. It was an empowering feeling, and it provided me with confidence. I went on the job market and secured a tenure-track job, I went on long hikes, I created zany programming at the writing center I directed at the time. I was capable and in charge. The picture above (see Fig. 5) was taken during my first pregnancy, 5 days before my due date (but 15 days before my son was born). In it, I am standing on the precipice of a butte wearing a jersey knit maternity dress with a bump bow and running shoes. I hiked frequently during my first pregnancy, usually on 3-5 mile trails in mountainous terrain. I hiked in my maternity dresses because I could, and I wanted to. Pregnancy made me confident and even a bit brazen. I felt this most fully during labor with my firstborn. My body was made to do powerful, strong things.

Dressing a Postpartum Body: Insufficient Glandular Tissue, Time, and Money

In the postpartum, everything about my body felt wrong, and it was impossible to dress it. I had a sweet, snuggly baby, but I was tired and felt like I had very little control about how I presented myself. I felt much less confident. The day after my son was born, I learned that I have a condition known as insufficient glandular tissue, which means that my breasts do not have enough of the kind of tissue that produces breast milk. This has nothing to do with their size, but it was another way my breasts have failed me. They don’t even do what they were designed to do. My small breasts and my inability to breastfeed make me feel less feminine, not even just less feminine but less female. Throughout my pregnancy, I wasn’t completely certain I wanted to breastfeed, so I was surprised at how devastated I was when I learned I could not breastfeed my son. This revelation negated many of the positive feelings I had about my body during pregnancy as did advertisements in my social media newsfeeds for nursing garments. I wore the nursing bras I’d purchased while still pregnant anyway (in fact, I’ve contemplated buying more of them because they are the most comfortable bras I’ve ever owned). I second-guessed my everyday decisions, my abilities, my career path, my motherly aptitude Everything felt harder postpartum, particularly after my second child was born. These feelings persist, even though my daughter is almost two years old.

My body and the difficulty I’ve had deciding how to dress it and frustration I’ve felt in not fitting into my pre-pregnancy clothing despite significant weight-loss, in a sense, represents my larger aimlessness about who I am and what I am here—in this world—to do. Since the birth of my son, my body has been difficult to dress, and I’ve felt like I’ve been in an amplified period of flux—starting new job while two months postpartum and trying to get the hang of being a mom, a resident of Indianapolis, and a tenure-line professor at the same time. Several significant parts of my identity changed in the span of just a few weeks, and I was trying to grapple with that in a body that didn’t feel like mine while trying to make a good impression on new colleagues. My hair was falling out, my stomach was blown out and resembled a flat tire (honestly, it still does), my belly also extended beyond my flat chest (and still does) but not in a cute way like the baby bump. Wearing maternity clothes, which were the most comfortable in the immediate postpartum period, made my no-longer pregnant body look pregnant, since they were made to accentuate round bellies. Most of my pre-pregnancy clothes were too tight. My chronic insomnia combined with an infant made for long nights and even longer days.

I began to regain a more coherent sense of self and then got pregnant again, which led me back into a cycle of self-questioning. I thought becoming a mother a second time would be easier, but it turns out almost all of it was harder. Since I was 35 at the time of my second pregnancy, I was considered geriatric, which required more screening, including weekly ultrasounds during the third trimester. The intensified monitoring of my blood pressure and blood sugar led me to question whether I was as good at being pregnant as I thought, whether I was as strong as I thought. Having a two-year-old child while pregnant with another child also meant that I got less rest during the second pregnancy. Most importantly, adding an entirely new person to a family is a lot of work. It takes a lot of time and energy, and the household dynamics, which had finally begun to take on a somewhat predictable rhythm, were completely shaken when my daughter arrived. Once again, my clothes didn’t fit and neither did I.

In the postpartum, I feel like I do not fit anywhere and everything—at work and at home—is harder than it used to be. I’ll illustrate this feeling with an example. Last spring one of my graduate students—formerly an undergraduate writing consultant at the UWC—was selected as part of our Elite 50, which is a celebration of our top fifty graduate students. As the student’s letter writer, I was invited to attend the award ceremony, which included a dinner. I had lost thirty-five pounds in the previous six months. On the day of the awards ceremony, a warm spring day, I selected a dress that hadn’t fit since before my first pregnancy. I was excited to be able to wear something that had been unavailable to me for a few (at least 4) years. In the mirror that morning, I thought I looked cute and professional in the light brown cotton dress with white polka dots without being stuffy or overly formal. I paired it with kitten-heeled yellow sandals and left for work.

Unfortunately, the weight across my body is distributed differently than it was when I last wore the dress, and—unbeknownst to me—when I sat down the dress gapped terribly at my bosom and showed my pink lace bra on my flat, flat chest. I noticed this issue a little during dinner but thought that I was handling it well through holding my shoulders just-so and avoiding any leaning. I learned the next day, however, that I had failed miserably. The student posted a picture of us from the event on her Facebook wall. In the photo (see Fig. 6; I cropped out the student), my bra is obviously showing. I hid the picture from my timeline, but I know several of my professional colleagues saw it. I thought about contacting the student and asking her to take it down, but I didn’t really want to write her a message about my boobs, so I didn’t.

|

Figure 6: Marilee, 16 months postpartum, April 2019.

At the time this photo was taken, my son was almost 4 and my daughter was 16 months old, well after the conventionally understood postpartum period of 6 months. Even so, I’m still adjusting to motherhood and a self and body that is in flux. Motherhood has, more than anything, highlighted for me that time and money are finite resources. Everything takes time and/or money, and it is a lot harder to come by both of those resources as a parent. That, in part, explains my poor choice of dress this spring. I hadn’t worn the dress in years, which means I probably should have worn it at a less high-stakes event first. I often need to wear camisoles with dresses in a faux-wrap style like this one, so I should have worn one that night, but I hadn’t been wearing dresses of this style as frequently and had, in fact, thrown out most of my pre-pregnancy camisoles while I was pregnant with my daughter because they were old and stained and then tossed the rest of them into a box out of frustration around a year after my daughter was born because very few of my pre-pregnancy clothes were fitting at that time. The box is in an odd corner of the basement behind boxes of baby and toddler clothes that my children have rapidly outgrown.

Mom Accessories for the WCA: Vacuum Cleaners and Performances of Class and Gender

In mid-August, I brought a vacuum cleaner to work. I thought that bringing it in before the semester started would mean that I wouldn’t run into other professors who might not be coming to campus regularly yet. Instead, I ran into two colleagues from my own department while walking to my building. Both of them asked me why I was carrying a vacuum cleaner through the campus center; you might be wondering as well. I direct a writing center, which is a physical space that, like our bodies, needs care and maintenance and is styled in a particular way. The UWC holds a unique role in the school and doesn’t conform neatly to typically understood definitions of office or classroom. It doesn’t get vacuumed often, and there are times when a small spill occurs and a vacuum of our own would be handy. We are not allowed to purchase janitorial equipment with our money since the purpose of our unit is not janitorial, but I happened to have a small vacuum cleaner I wasn’t using at home, so I brought it in to make it easier to tidy up the UWC without having to put in a work order with facilities. In a sense the vacuum cleaner and things like it are accessories I wear across campus, accessories that contribute to perceptions about me and the UWC. Accessories like the vacuum cleaner (see Fig. 7), the printer I once carried from one UWC location to another, and the trays of cucumber sandwiches I bring to UWC staff meetings are part of my sartorial performance as writing center director. These accessories point to a professional identity that is classed and overtly gendered in ways that is not the goal for most tenure-track professors.

|

Figure 7: Vacuum cleaner at the University Writing Center, August 2019.

These particular accessories aren’t worn by most in academic workspaces, and they reinforce the notion of WCA as “mom” and the writing center as “home,” in that they are associated with domestic labor. The idea of writing centers as home-like places is a topic of much debate and concern. Jackie Grutsch McKinney (2013) writes, “Female directors who insist on cozy, inviting spaces may be unwittingly narrating their work as non-intellectual in the eyes of some. Fact is, if the writing center is home and the staff is family, that makes the director the mother” (p. 26). She sees the home-like connotations of writing centers as problematic for female directors, asking us to distance ourselves from the “feminine” associations of “cozy” writing centers. In addition, her critique and others also point out that the “cozy” and familial associations of writing centers reinforces the mainstream notions of family and home, therefore “mirror[ing] the creepy, capitalist, white, cis family structure” (Dixon in Baldwin et al., 2018). Elise Dixon posits that this association of the writing center as family has

meant that I’ve done a lot more labor as a woman in the writing center than my male counterparts. It’s meant that I’ve seen trans, non-binary, and gender deviant friends get misgendered, ignored, and avoided in writing center spaces. It’s meant that I’ve seen my friends of color get mistaken for other people of color by clients and consultants in common micro- and macro-aggressive behaviors. (Baldwin et al., 2018)

Many of my experiences as a graduate writing consultant were similar, and I see these same concerns and interactions as a WCA. I worry more now, as I am more responsible for what happens in the writing center. That responsibility does have similarities to my performance as a mother at home.

At work or at home, I’m “mom”—washing dishes, soothing hurt feelings, listening to the concerns of our home/office community, keeping the household/office organized, scheduling doctor’s appointments/committee meetings, reminding our partners/staff of upcoming commitments, vacuuming the house/writing center. This is necessary work, but professors often see themselves as focused primarily on teaching and scholarship, which seems removed from the kind of management and service-focused tasks of running a writing program. I feel caught in between identities—those that I’ve come from and those that I aspire to. My entry into motherhood has me reflecting more and more on my past experiences and identities and the process of “re-knowing my story, revisiting where I had come from and examining how that story lives within—and influences—me even today” (John Gagnon in Smith et al., 2017, p. 54). I feel conflicted and frustrated about wanting to progress beyond my working-class roots but also irritated when I am asked or expected to participate in service-based (nurturing and mentoring) labor that other colleagues of similar status and rank are not.

Class identity is one of those things that can be visible, as seen through wearing clothes until they almost literally fall apart, not knowing how to dress for formal events, but can also be an invisible status, particularly if you have a tenure-track job at a university. Writing of the literature on writing pedagogy, Julie Lindquist (2004) says that class is “simultaneously everywhere and nowhere” (p. 189). Of writing center scholarship, Harry Denny and John Nordlof (2018) similarly share that “working-class students are everywhere and nowhere” (p. 71). This might be, in part, because “working-class culture differs from other categories of difference. It is marked neither as an identifiable category, like gender, nor as a unified set of historical practices. It names, rather, a set of shared experiences fraught with structural tensions and contradictions” (Lindquist, 2004, p. 192). Students often come to college for opportunities that will move them from the working class to the middle class. It’s part of the progress narrative that colleges tap into to recruit students.

As a person raised in a working-class family, I have a hard time knowing how to be both working-class and middle class, how (not) to perform. I am privileged in this institution and the profession of WCA; I have a tenure-track appointment, an office with a window, and a fairly balanced assignment across teaching, administration, and research with significant autonomy over how I spend my time. Even so, I feel like I am like part of the almost-middle class of the institution. I am the first tenure-track writing center director on this campus, and my position often gets conflated with that of staff members due to the significant amount of administrative labor and the rare academic assignment that places me in charge of a physical space. I am frustrated with myself by wanting more consistent recognition of my status as tenure-track faculty, but see it as potentially productive in gaining respect for the UWC and the discipline of writing studies from institutional colleagues. At the same time, I recognize the importance of the administrative labor of staff and the heavier teaching loads of my non-tenure-track colleagues and see a need for the institution to value that work through better working conditions, pay, and benefits. In other words, I want to maintain the class privilege I’ve “achieved” while realizing it is not accessible to everyone and is a problem. These contradictions are evident in my dress practices, through accessories like the vacuum and through complications in dressing my postpartum body, which makes my identity as a mom visible and accessible for commentary to my professional colleagues.

Should I be frustrated that vacuuming the writing center is sometimes part of my job? What does the vacuum and other workplace accessories I’m found carrying through the halls say about me and my ability to be seen as a tenure-track professor? Lindquist considers “how teachers might position themselves to gather data from students in order to learn who they must become in order to enable a fuller range of experiential and affective responses” (p. 202). I’d argue this is true of all our work in the academy. For writing program administrators, this includes engaging in impression management across interactions with various groups of stakeholders to secure funding, persuade writers to make writing center appointments or enroll in our classes, and convince colleagues across the disciplines to adapt their writing pedagogies. These interactions, of course, include face-to-face meetings, emails, word-of-mouth messages from colleagues and students, but the medium is the message, and that medium includes our bodies. Interactions, then, also include how we hold our bodies, how we move our bodies, how we dress our bodies, what kind of bodies we inhabit, and the experiences, feelings, and attitudes that our audiences associate with bodies like ours and how they should(n’t) move, speak, write, or look.

Conclusion: More Demands, Fewer Rewards

We are expected to be tenure-line faculty members who publish as well as take on significant administrative labor typically assigned to staff or tenured faculty. We are not just talking about how our discipline hasn’t been valued as highly as other academic disciplines, or how our work as WPAs is seen as “service” and therefore the least valuable of the academic labor triad (consistently valued in this order: research, teaching, service), but also how those concerns are mingled with gendered, physical realities. Female bodies are expected to perform nurturing, service-focused labor in academic spaces, even though that labor—while important and expected—is not valued through increased compensation or promotion. Dress practices are expected to emphasize our female labor; we are expected to wear clothing that identifies us as a nurturing body, whether that be through wearing clothing that accentuates our female body to “dressing like a mother” with mom jeans, flowy tops, or comfortable fabrics. In this way, identity comes through in our body work of dress practices: “All bodies do rhetoric through texture, shape, color, consistency, movement, and function. Embodiment encourages a methodological approach that addresses the reflexive acknowledgment of the researcher from feminist traditions and conveys an awareness of consciousness about how bodies—our own and others’—figure in our work” (Johnson et al, 2015, p. 39). Our narratives focusing on dressing our pregnant and postpartum bodies demonstrate the embodied approach of identity creation. Like Johnson et al. (2015) we recognize that “embodied methodologies and embodied rhetorics encourage complex relationships among past, present, and future, as well as across multiple identifications” and see our work contributing to conversations about how “bodies both inscribe and are inscribed upon” (p. 42).

In the classroom, women are also held to standards that require us to be seen as nurturing, and we are told that we must demonstrate this nurture through our cultivated identities, which sometimes may be seen through our dress practices. In the past we have read comments about our dress practices in our end of semester student evaluations. Comments will share thoughts about our bodies and how we dress our bodies, but will not comment about our expertise or teaching effectiveness. For example, a comment may share that we do not dress like we are a professor because we may not wear items that make us look like a professor. Alongside the expectations of dress, we are also expected to act nurturing, and if we act nurturing enough, we will be told in our evaluations that we are nice and caring and other students should take our classes specifically because we are nurturing. El-Alayli, Hansen-Brown, and Ceynar (2018) summarize these expectations,

In expecting and perceiving female professors to be more nurturing, students are essentially expecting them to function like academic mothers. Increased nurturance demands on women in academia may cause them to perform more emotional labor with their students. Female professors may find that they must take on extra burdens, such as helping students cope with stress or insecurities, having to set personal boundaries with them, or providing gentler feedback to them to avoid being perceived as excessively harsh. (p. 137)

Their study indicates that students hold female professors to different and higher standards than male professors, requiring female professors to spend considerable time and energy negotiating and addressing the demands placed upon them. They find that “the same academic job may require more time, personal, and emotional demands from female faculty than from male faculty” (140). Further, as women academics we are expected to dress our role, meaning crafting dress practices that emphasize our femaleness so that we can be seen as nurturing, caring bodies. As mothers, our bodies give ourselves away, as shown through recollected conversations with our colleagues who have asked about a pregnancy when we were not pregnant. Our bodies carry the burdens of our previous pregnancies. Sometimes we wear clothing in efforts to hide our postpartum bodies. At other times our dress practices give comfort to our postpartum bodies in how we choose stretchy clothing or soft fabrics. Our dress practices have thusly been influenced by how our bodies have changed and will continue to change.

Finally, composition and writing centers are frequently constructed as a place of continued nurturing to our students. Our students arrive without their parents, and some students are living far away from home for the first time, and so our academic spaces are areas where it is at least possible to be motherly. Just as our mom bodies are commonly seen as spaces of nurture for our children and our families, the academic spaces of the writing center and the composition classroom all hold a historical narrative toward being viewed as cozy, comfortable spaces (Grutsch McKinney, 2013; Ballif, et. al, 2010). Narratives focusing on nurturing may limit our professions, our academic spaces, and ourselves. If what we do in a writing center or with a writing program is a pedagogy of care, we wish to illustrate that creating an ethics of care needs to be a concern for all humans, not solely the work of women or mothers.

[H]elping writers doesn’t involve just supporting the formation of that identity in isolation from all the others that make up who we are and the communities with which we identify or that we aspire to join. All of who we are commingles and spurs each of our identities in parallel and divergent ways. For faculty, administration, or tutors in writing centers, we too are growing and being shaped by multiple forces within, outside, and across us. Who we are is an amalgam of past, present, and future. There forces are critical, yet we rarely have the language or occasion to speak into and interrogate them. (Denny, 2018, p. 120)

The passage above from Denny is apropos to our narratives shared above: both of us have written of the ways we support our families, ourselves, students, and colleagues, but we have also written of the ways we feel a lack of support. We each have described how we have modified our dress practices and our academic spaces to cultivate new systems of support for ourselves. None of this work has been, or ever is, easy work. The balancing act inherent within what we do is tricky, leaving ourselves to question if the time we are devoting to one facet of our lives is enough. Denny notes that we “rarely have the language or occasion to speak up and interrogate” the forces that surround us, but in the narratives we have shared, we created a space to do just that: speak up and interrogate our institutional and bodily borders.

References

Ahmed, S. (2017). Living a feminist life. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Baldwin, D., Brentnell, L. Dixon, E., Donelson, J., Firestone, K., & Robinson, R. (2018). Big happy family. The Peer Review, 2(1). Retrieved from http://thepeerreview-iwca.org/issues/relationality-si/big-happy-family/

Ballif, M, Davis, D., & Mountford, R. (2010). Women’s ways of making it in rhetoric and composition. New York, NY: Routledge.

Bourdieu, P. (1990). Photography: A middle-brow art. Cambridge, England: Polity Press.

Cedillo, C.V. (2018). What does it mean to move?: Race, disability, and critical embodiment pedagogy. Composition Forum, 39(1). Retrieved from http://compositionforum.com/issue/39/to-move.php

Cultural Rhetorics Theory Lab (M. Powell, D. Levy, A. Riley-Mukavetz, M. Brooks-Gillies, M. Novotny, & J. Fisch-Ferguson). (2014). Our story begins here: Constellating cultural rhetorics practices. Enculturation: A Journal of Rhetoric, Writing, and Culture, 18. Retrieved from http://enculturation.net/our-story-begins-here

Denny, H. (2018). Of queers, jeers, and fears: Writing center as (im)possible safe spaces. In H. Denny, R. Mundy, L. M. Naydan, R. Severe, & A. Sicari (Eds.), Out in the center: Public and private struggles (pp. 117-125). Logan, UT: Utah State University Press.

Denny, H., & Nordlof, J. (2018). “Tell me exactly what it was that I was doing that was so bad”: Understanding the needs and expectations of working-class students in writing centers. The Writing Center Journal, 37(1), 67-100.

Edelman, M. W. (2018). Moving between identities: Embodied Code-Switching. In C. Caldwell & L.B. Leighton (Eds.), Oppression and the body: Roots, resistance, and resolutions (pp. 181-204). Berkeley, CA: North Atlantic Books.

Eicher, J.B. (2000). Anthropology of dress. Dress, 27, 59-70. Retrieved from the University of Minnesota Digital Conservancy, http://hdl.handle.net/11299/162782

El-Alayli, A., Hansen-Brown, A. A., & Ceynar, M. (2018). Dancing backwards in high heels: Female professors experience more work demands and special favor requests, particularly from academically entitled students. Sex Roles, 79, 136–150. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-017-0872-6

Enbeau, S. D., & Buzzanell, P. M. (2010). Caregiving and female embodiment: Scrutinizing (professional) female bodies in media, academe, and the neighborhood bar. Women and Language, 33(1), 29-52.

Fox, B., & Neiterman, E. (2015). Embodied motherhood. Gender & Society, 29(5), 670-693. doi:10.1177/0891243215591598

Gonzalez, A. M., & Bovone, L. (2012). Identities through fashion: A multidisciplinary approach. Oxford, England: Berg Publishers.

Green, F.J. (2008). Feminist motherline: Embodied knowledge/s of feminist mothering. In A. O’Reilly (Ed.), Feminist mothering (pp. 161-176). New York, NY: SUNY Press.

Johnson, M., Levy, D. Manthey, K., & Novotny, M. (2015). Embodiment: Embodying feminist rhetorics. Peitho, 18(1), 39-44.

Jorgenson-Borchert, J. (2019). A narrative of breastfeeding after a high-risk twin pregnancy. Survive and Thrive: A Journal of the Medical Humanities, 4(1), Article 20.

Kinser, A.E. (2008). Mothering as relational consciousness. In A. O’Reilly (Ed), Feminist mothering (pp. 123-140). New York, NY: SUNY Press.

Lindquist, J. (2004). Class affects, classroom affectations: Working through the paradoxes of strategic empathy. College English, 67(2), 187-209.

McDowell, L. (1999). Gender, identity, & place: Understanding feminist geographies. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

McKinney, J. G. (2013). Peripheral visions for writing centers. Logan, UT: Utah State University Press.

Miley, M. (2016). Feminist mothering: a theory/practice for writing center administration. WLN: A Journal of Writing Center Scholarship, 41(1-2). Retrieved from https://wlnjournal.org/archives/v41/41.1-2.pdf

Nicolson, P., Fox, R., & Heffernan, K. (2010). Constructions of pregnant and postnatal embodiment across three generations. Journal of Health Psychology, 15(4), 575-585. doi:10.1177/1359105309355341

Neiterman, E. (2013). Sharing bodies: The impact of the biomedical model of pregnancy on women’s embodied experiences of the transition to motherhood. Healthcare Policy | Politiques De Santé, 9(SP), 112-125. doi:10.12927/hcpol.2013.23595

Oliver, K. (2010). Motherhood, sexuality, and pregnant embodiment: Twenty-five years of gestation. Hypatia, 25(4), 760-777.

O’Reilly, A. (2007). Feminist mothering. In A. O’Reilly (Ed.), Maternal theory: Essential readings (pp. 792-821). Ontario, Canada: Demeter Press.

Price, M. (2011). Mad at school: Rhetorics of mental disability and academic life. The University of Michigan Press.

Smith, T., Manthey, K., Gagnon, J., Choffel, E., Faison, W., Secrist, S., and Bratta, P. (2017). Reflections on/of embodiment: Bringing our whole selves to class. Feminist Teacher, 28(1), 45-63.

Turner, P. K., & Norwood, K. (2013). Unbounded motherhood. Management Communication Quarterly,27(3), 396-424. doi:10.1177/0893318913491461

[1] My university’s family leave policy is connected to sick leave. All faculty accrue 2.5 hours of sick leave per two-week pay period. This system directly benefits senior faculty who have been able to accrue enough sick leave over a few years. As a new faculty member, I did not have much sick leave stored up. We do have a sick leave pool, but in order to use the sick-leave pool I would have to donate some of my sick leave. Because I had not been employed a full year, I was not yet eligible for FMLA and FMLA is unpaid. I am the sole earner for my family, so I needed paid leave. For fuck’s sake, please give new parents paid family leave in the United States.