Arachnid

Alysa Robin

Keywords: child care; isolation

Categories: Parenting as (Im)possibility in Impossible Circumstances; Reflecting on Academic (Over)work and/or Precarity; Reflecting on and Refusing Racial and/or Gender Inequity

Louise Bourgeois THE NEST, 1994

Steel; 101 x 189 x 158"

Collection and photo: San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

© The Easton Foundation/VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

When we sheltered in place, I imagined myself as the mammoth mother spider protecting her children, as rendered in Louise Bourgeois' The Nest. Two years earlier, I stood in front of The Nest at the San Francisco MOMA, entranced by the symbolic power of this mother spider. In Bourgeois' sculpture, the mother creates a canopy with her bulbous, pregnant body and eight spindly legs, protecting her spiderlings from predators. The Nest signifies the gravity and a cultural code of motherhood, that of the protector, the caregiver. In Rhetorics of Motherhood, Lindal Buchanan states, "Like gender, the code is contextually bound; therefore, its constitution varies across time, cultures, locations, and communities" (p. 6). The Nest takes on amplified meaning at the onset of the pandemic. The fear of the unknown, social destruction and interruption of daily routines destabilized our very existence; The Nest embodies the shared feelings of the fears and responsibilities of mothering across contexts during this time. During early Covid times, I thought of the mother spider's body and ability to shape her physical being into a safety nest.

I do not have eight spider legs to contort into a safety nest. I address this with my limbs stretching into analog and digital spaces. I took for granted how much routine in common spaces created a sense of purpose, normalcy, and stability. Looking back, care involved attempts to recreate stability for those in both the analog and digital nests to ensure (or try to) the well-being of others.

Sheltering-in-a-domestic-place becomes the physical nest. Zoom becomes the digital nest. The nests include:

- Three children.[1]

- Two dogs.

- Six virtual college writing classrooms.

- Up to twenty virtual writing center conferences each week.

I recall an image of Maman, Bourgeois' monumental 30-foot-plus bronze mother spider. The description of Maman states, "The spider, who protects her precious eggs in a steel cage-like body, provokes awe and fear, but her massive height, improbably balanced on slender legs, conveys an almost poignant vulnerability" (Dailey). This haunting sculpture imprinted in my memory for years. bell hooks states, "...public art can be a vehicle for sharing of life-affirming thoughts" (xvii). In this pandemic context, Maman connotates the massive fears and anxieties linked to the vulnerability of motherhood. No sturdy legs or house made of bricks could dissipate the worry of caring for others in the face of the unknown. The placement of Maman in a public space, coupled with the massive size of Maman's body and the empty negative space, amplifies these shared fears of maternal anxiety.

Maman's legs are sturdier than those sculpted for The Nest. They are thicker, more rope-like, muscular, limber, woven braids of bronze metal, yet like in The Nest, the material speaks, showing motherhood's dichotomy. The spider, stealth-like, carrying a full sac of eggs, balances the weight of embodying the role of protector on eight narrowed pencil tip-like points. With the body, the mother spider doesn't consider whether she is the protector; she doesn't consider her role or purpose. Instead, the mother spider protects; a mother spider has maternal instinct.

View of Louise Bourgeois's MAMAN (1999) installed at the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, Bilbao, Spain, 2007. Photo: Erika Ede

© The Easton Foundation/VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

In a zoom meeting, a colleague informs me that I always wear the same navy-blue winter vest. She says it's your thing, your armor. As Jack Selzer asserts, "material realities often (if not always) contain a rhetorical dimension that deserves attention: for language is not the only medium or material that speaks" (p. 8). Until then, I did not realize that I was slipping on a "steel cage-like" exterior.

As stated in Empathy and Moral Development, the definition of empathy is "an affective response more appropriate to another's situation than one's own" (Hoffman 4). It's not just about creating physical and virtual space(s) but rethinking what is happening inside the nests to consider each other’s pandemic experiences This requires labor[2] in thinking time, planning time, and creative ways to make space for addressing our collective vulnerability.[3] In our zoom spaces, routines include storytime. Students shared stories that were worrisome, heartbreaking, and sometimes funny. At home, the communal space is the kitchen, where cooking, procrastibaking, and meals are the times we share moments of our zoom-filled days.

There is no how-to manual; I continue to stretch limbs between analog and digital. There is no second shift; the shift becomes a singular entity. Work creeps into the home nest, home creeps into the work nest. I zoom into a classroom in the quietest place I can find – with the washing machine as my desk. I wonder if students can see my to-do list, hear the washing machine hum, the dryer spin, and the dogs bark. Between classes, I check on soup simmering and see my eldest daughter perched over her computer in the kitchen. I listen in on a zoom lecture on China and American foreign policy. I stir, then strain the soup. I ladle a scoop of broth, chicken, carrots, and noodles into a bowl for my son, who slides into the kitchen trailed by our two dogs. I wash whatever is in the sink when my other daughter carries in her computer; we all hover around watching a guest speaker from the Innocence Project zooming into a high school event. I cry from the first-hand account of unjust incarceration.

The mothers I speak to (and follow in digital spaces) are equally fatigued with impossible choices and attempts to create stability where there is none. While the blurring of the lines is provides the flexibility of not being pulled between home and work, the blurring of the lines fatigues (as work happens in snippets and at all hours and odd hours). As described in Dr. Laksmin's article, "How Society Has Turned Its Back on Mothers," burnout is an outdated and inaccurate term, as this word does not represent the “depth of despair.”[4]

During this time, I read The Argonauts. Maggie Nelson states, "You are responsible for his welfare but unable to control the core elements" (93). While Nelson refers to becoming pregnant, I connect the ideas to mothering and teaching in the pandemic. Being responsible for the welfare of others during these times requires more time. Physical. Mental. Emotional. Cognitive. Domestic. Patience. Compassion. Would Dr. Winnicott say I am a "good enough mother"? Julia Kristeva would say I am not a "good fairy" mother. Kristeva suggests that "good fairy" mothers that sacrifice themselves do not feel pain or fatigue (Oliver, p. 17). I AM fatigued. Kristeva states in "Motherhood Today," "As long as she's alive, the mother is there to guarantee life to the best of her ability, whatever the conditions." In Bourgeois' sculptures, I am reminded of the mother code as the protector, transcending in these abnormal times.

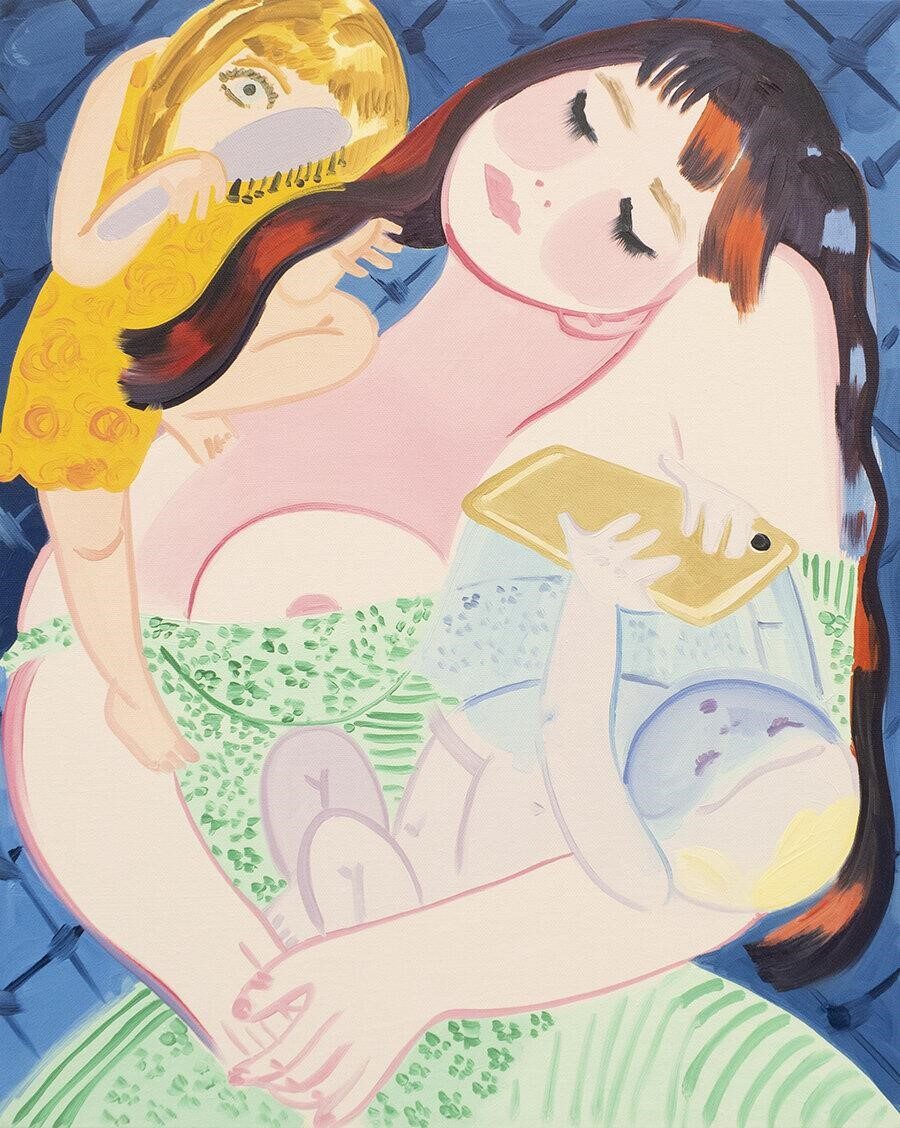

Madeline Donahue’s THE DREAM (2020)

© Madeline Donahue

While the spider mother's body is metaphorically powerful in Bourgeois' art, Madeline Donahue puts intimate lived experiences of motherhood in full view close-up and color. Her artistic choices reveal a refreshing and honest look at private moments of the chaos of care during Covid times. Her work is not about fear but rather the ambiguities of care in motherhood: love, joy, responsibilities, and fatigue. Donahue's art is an insider's nod to other mothers who know; the private we have all been there moments. I chuckled when I initially noticed the piece scrolling by in my Instagram feed. While her renderings are approachable and joyful, these do move past everyday shared experiences and ask the viewer to look deeper into the role and expectations of mothering, particularly during Covid. At first glance, there is joy, wit, and frenetic energy. A closer look reveals the privacy of the moments and the central position of the mother's body, as well as references to pop culture distractions (phone) and domestic spaces (baking). Donahue pointedly chooses to use the mother's body as the central focus to show a mother's lived experience as the vehicle of protection. Breasts exposed, limbs stretched, and her body poked and prodded. In "Embodiment: Embodying Feminist Rhetorics," Maureen Johnson et al. state, "All bodies do rhetoric through texture, shape, color, consistency, movement, and function" (p. 39). The subject's arms in The Dream become the nest and the children are the mother's appendages. Buchanan asserts, "the code's well-known standards and affiliated emotions imbue motherhood with enormous force and significance" (p. 117). Limbs on limbs, Donahue's subject's body is the space that enacts care (and love); this mother is the mother spider.

Madeline Donahue’s SCALES, 2022

© Madeline Donahue

It is those tiny moments Donahue renders that prompt me to remember moments of care and mothering during the onset. While my children are not little, memory has been triggered “by a chance incident or light or shadow” (Farr 15). In spending the time to create moments of routine and stability, I think I was trying to develop good memory-images in light of the fear of the unknown. Would my kids remember a specific meal we cooked together? Would students remember having the time to share moments of their time while sheltering-in-place? Having room for those tiny new moments of possible joy and connection in both the virtual and physical nests is perhaps what I hoped would distract and suppress the more significant concerns for all in the nests. I wonder what will trigger me to remember and hold on to the tiny moments during these times. While chaotic and unsettling and a constant juggle and exhaustion, I must acknowledge how we carried on and try to hang on to the sliver of a silver lining by remembering moments of togetherness, creativity, chaos, and new rituals.

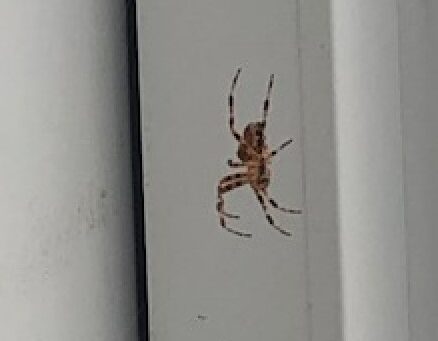

During a zoom session in May, a spider dangles beneath a molding. The spider’s bulbous body dances up and down building The Nest. I call the kids to see the spider. My son looks at me and says, It’s spring. Time to take off the vest. As we watch the spider dance, I stretch my arms out wide; my fingertips reach around them. After boredom sets in, they trail back to their respective zooms. The washing machine spins, dogs bark, zoom lags. I zip up my vest. Routine seems to have set in.

References

Barthes, R. (1997). Image music text. Hill and Wang.

Bourgeois, L. (1994). The nest. [steel sculpture and photo]. San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. San Francisco, CA.

Bourgeois, L. (1999). Maman. [steel sculpture; photo by E. Ede]. Guggenheim Museum Bilbao. Bilbao, Spain.

Buchanan, L. (2013). Rhetorics of motherhood. Southern Illinois University. Carbondale, IL.

Dailey, M. Louise Bourgeois. The Guggenheim Museum and Foundation. Retrieved from https://www.guggenheim.org/artwork/10856

Donahue, M. (2022). The dream. [photo of painting]. Retrieved from http://www.madelinedonahue.com/

Donahue, M. (2022). Scales. 2022. [photo of painting]. Retrieved from http://www.madelinedonahue.com/

Farr, I. (2012). Not quite how I remember it. In I. Farr (Ed.), Memory (pp.12-27). MIT Press.

Hoffman, M. L. (2000). Empathy and moral development: Implications for caring and justice. Cambridge University Press.

hooks, b. (2018). All about love: New visions. William Morrow.

Johnson, M., et al. (2015). Embodying feminist rhetorics. Peitho, 18(1), 39-44.

Kristeva, J. Motherhood today. Retrieved from http://www.kristeva.fr/motherhood.html

Nelson, M. (2016). The argonauts. Graywolf.

Oliver, K. (2008-2010). Julia Kristeva’s maternal passions. Journal of French and Francophone Philosophy, 18(1), 1-8. DOI: 10.5195/jffp.2010.172

Selzer, J. (1999). Habeas corpus: An introduction. In J. Selzer & S. Crowley (Eds.), Rhetorical Bodies (pp. 3-14), University of Wisconsin Press.

[1] Their father is also partially quarantined in our nest and a nest of another. The Zoom nest could include up to 80 students in one day between classes at two different universities and writing center hours at a third.

[2] Motherhood labor during Covid and the economic impact of the motherhood penalty deserves a much deeper dive. A Brooking Institute study shows how mothers of children under 12 spent an average of eight hours per day on childcare. Working mothers spend six plus hours working on top of childcare. We know too well about the unpaid (and invisible) domestic doldrums and Extreme Domesticity. But what about perceptions and portrayals of motherhood and responses in public discourse during the pandemic considering time-use research?

[3] "Empathy After 9/11" discusses empathetic responses. Creating a routine for those in the nests was an earnest attempt at an empathetic response. I acknowledge that it’s not so simple to create stability or re-creating a routine as the answer, nor do I mean to romanticize the response. I share my experience knowing this is one experience. While there is the common thread of added labor, individual stories of parenting, caregiving, and mothering are unique. Some days procrastibaking, binge-watching TV with the kids, and scrolling through the horrors of the news was all that could be managed.

[4] For all the disruption, I can’t help to think about mothers with young children and those who were unable to continue to work. Considering those with younger children, the crisis of a broken system was more than attempting to balance each day, as evident in "Tracking Job Losses for Mothers of School-Age Children."

Despite cobbling work together with three part-time contingent jobs, I did not leave the workforce.

Bio

Alysa Robin Hantgan is a lecturer in the Writing and Cultural Studies department at Pace University. She received an MFA in Fiction from Sarah Lawrence College with an undergraduate degree from the University of Michigan.