VIGNETTE 1: COLLECTING AND CURATING COMMUNITY EXPERIENCES

On this page, we narrate the sessions that focused on eliciting community experiences to shape into digital stories for the project.

Critical consciousness and finding the stories

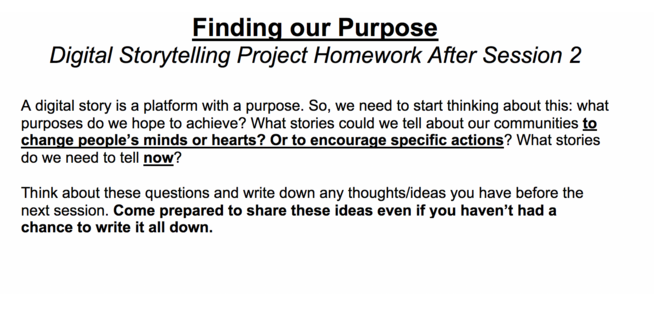

The of the most important stages of our digital storytelling project was the third workshop session, which we called “Finding the stories.” We thought carefully about how to craft the session to evoke, bring together, and draw out stories of shared experiences. Prior to the session, we had assigned youth homework prompting them to think about the kinds of stories they’d like to tell.

Figure 1. Homework Prior to "Finding the Stories" workshop session

We prepared the session by placing large posters of the purposes a story might serve all over the room: to educate or bring awareness; to have new or often silenced voices heard; to change people’s minds; to encourage a specific action.

Once the stage was set, we began with an “icebreaker” activity that prompted everyone to sit in a circle and tell the story of their name. While still in this storytelling frame of mind, we transitioned to the next activity: reviewing the purposes stories can serve in order to think about what stories we want to tell with our digital stories.

We then broke up the group of 12 participants into 4 groups of 3, with one youth coordinator or university researcher assigned to each group to take notes as the youth shared the stories that they thought we should tell. As soon as everyone settled, the ideas began to spark, or as one of youth coordinators later put it, “the bomb went off;” the ideas generated like waves building across the participants. Brief excerpts from Jenna’s fieldnotes illustrate this generative process, though we take care not to divulge too much of this brainstorming exchange as some of these elements were not chosen by the youth storytellers for creation and dissemination. [Read the excerpts]

Time flew by during this short activity. One of the youth coordinators, Eric, actually had to be the one to remind us that we were going to bring the shared stories to the large group. From our undergraduate researcher’s notes on the session, we came to understand that all small groups essentially went this way. Once we finally gathered everyone into a large group, we asked for representatives of the small groups to begin sharing what they had discussed. We prepared large posters labeled, “What stories do we want to tell?” and “What purpose do you think our digital stories might serve?” to write on as the youth reported the ideas that emerged from our small group discussion. Youth storytellers brainstormed five possible purposes they could achieve by telling collective stories about their experiences in Lowell, the last one receiving the most ideas: “Changing the school system/environment” to address their heart-wrenching experiences with bigotry, fights, bullying, buildings (that have problems), dress code injustices, and the administration not acting on students’ reports of problems at school.

As the students spoke in large group, more details emerged, and the energy again built across disparate experiences. The adults exchanged horrified glances, deeply disturbed by the things the students were saying about school. Again, we had to interrupt the moment to end the session. Even though it felt hard to end, we prompted the youth storytellers to start thinking about which of these ideas is the most important to tell right now since we had to identify two or three issues to address in collaboratively created digital stories within the span of the 10 sessions that was allotted to us.

The session would have just ended, with our bodies in knots and our minds racing, had it not been for one of the youth coordinators, Eric, who asked everyone to gather in a circle before they left for the night. Eric looked us all in the eyes and thanked the youth for being brave enough to tell these difficult stories, something that he acknowledged is hard to do in a space like this. He apologized to them for having to deal with what we wrote on the posters and for having adults like that in their lives. He said that the youth coordinators and “our new friends from UMass Lowell” are here to be a positive force in their lives. That we (the adults) will always listen and act on what they tell us. That we believe in them and that we will help them make the changes they want to make. Following his lead, we each put a hand in the center of the circle and chanted in unison about being the change that we wanted to see in the world. At a climactic point in the chant, we threw our hands in the air and cried out “YAY!”

Eric’s response, described above, is an important contribution to our thinking about participatory curation as a critical-creative rhetorical performance and integral intermediary moment in a participatory project. As such, during his interview, we asked Eric to elaborate upon why he gathered everyone in a circle that day. He explained:

"I think having something to bring it full circle so there’s a sense of closure. Because I think that's always the tough thing. It's really emotional and after all these stories come out you can be left in a really vulnerable place. . . It can be really good because (you) get a lot off your chest. But, then, how do you bring people back down so that when they leave they're not still sunk in that place of all the crappy things of the stories they were telling? . . .I don't think you can ever really figure out but I think emphasizing, ‘Hey. We're here for you. But, also, you guys are here for each other.’ This is something...Even if it's a circle up, it symbolizes we just did a lot of work on our own we shared. But we're still connected in this circle here. We're still connected with each other. I think it's a sense of closure before you leave that space is important." (Emphasis added)

We concur with Eric that the process of eliciting and sharing the stories was “really emotional” and potentially left youth in “a really vulnerable place” having bared all the ways in which they are vulnerable: to teachers, to parents, to school security guards, to police, to administration. Eliciting their creative retellings of these events, collecting these experiences, and showcasing them on a poster, we could have just stored them for meaning-making later and walked away—admittedly what we almost did before he intervened. Circling up, looking each other in the eyes, and stating adult accountability and support of the younger participants was a means of building trust and committing to truly participate with them to get these stories fleshed out and heard. This “symbol” of “connected” nature was both enacted and reflected in that circling up. Together, with the youth coordinators and the participants, we curated a participatory moment.

The brainstorming session during Session 3 was, essentially and strategically, a critical consciousness raising session. As youth storytellers wrote on their anonymous feedback slip submitted at the end:

This session was very educational and it got to the point where it helped me to relate to and think about the few things that took place in my life in the past couple of months!

I enjoyed the communication and connection we were able to make with each other.

Felt that it was a great session to go over because things are not only happening to you but everyone else in the room. It shows that we are all much alike in many ways.

As feminist, participatory action researchers this was a clear success. Participants were sharing experiences, listening to differences in each other’s experiences while also finding vibrant lines of connection between their experiences at school and in the community. The youth coordinators were involved and facilitating alongside us, contributing in terms of collecting youth storytellers’ ideas, prompting more ideas, and determining needed moments in the workshop on the spot.

It felt right. It felt important. And yet, it was also overwhelming to hear how often and in how many ways the youth felt they were not being heard or they were being actively harmed or invisibilized.

We stood in a slow drizzling rain outside the youth center afterwards, clutching the rolled-up poster paper, engaging in the little theorized but nonetheless difficult labor of self-reflexivity: what had just happened? Why did it happen that way (it felt right)? How can we proceed with our very time-limited and practical goal of producing 2-3 digital stories while still engaging in thoughtful praxis? As critical, feminist researchers, we were guided by an ethics or imperative “to inhabit a sense of caring about the people and the process involved” (Rosyter & Kirsch, 2012, p. 145). How would we ever do a critical curational move: Showcasing/framing some of these experiences and leaving others in the drawer, so to speak? How can we do this while making sure that the context remains affirming and empowering for the youth?

Curation as care, cultivating participatory decision-making

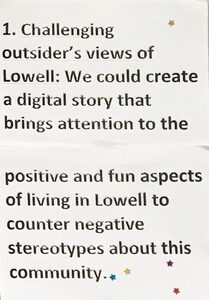

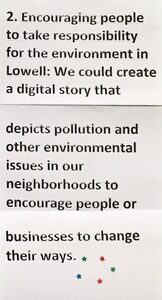

After a restless night or two we came back together with the idea of curating an exhibition of all the possible ideas the youth storytellers had brainstormed to enable a collective vote. We needed to curate their experiences, by which we mean showcase them, in a way that showed we (adults in this relation to youth, and researchers at a respected local university in relation to youth recruited to our project) heard them, validated their experiences, and authorized them to collectively choose what we should focus on. Part of the participatory curatorial praxis, we have learned, is to build the relationship and context so that the participants choose when, if, and how to tell their experiences. Curation then represents an opportunity for us, university affiliated researchers, to establish reciprocal, participatory creation of knowledge, striving to ensure that each participant has an opportunity to voice their perspective on when, if, and how to exhibit co-created knowledge. This we felt could be best realized by having the participants collectively review what we had created during the previous session but ultimately vote on which stories they needed to tell now with digital stories. Toward that end, we drew upon our strengths in rhetoric and narrative to translate the many brainstormed ideas into 10 succinct ideas for digital stories with a clear rhetorical purpose.

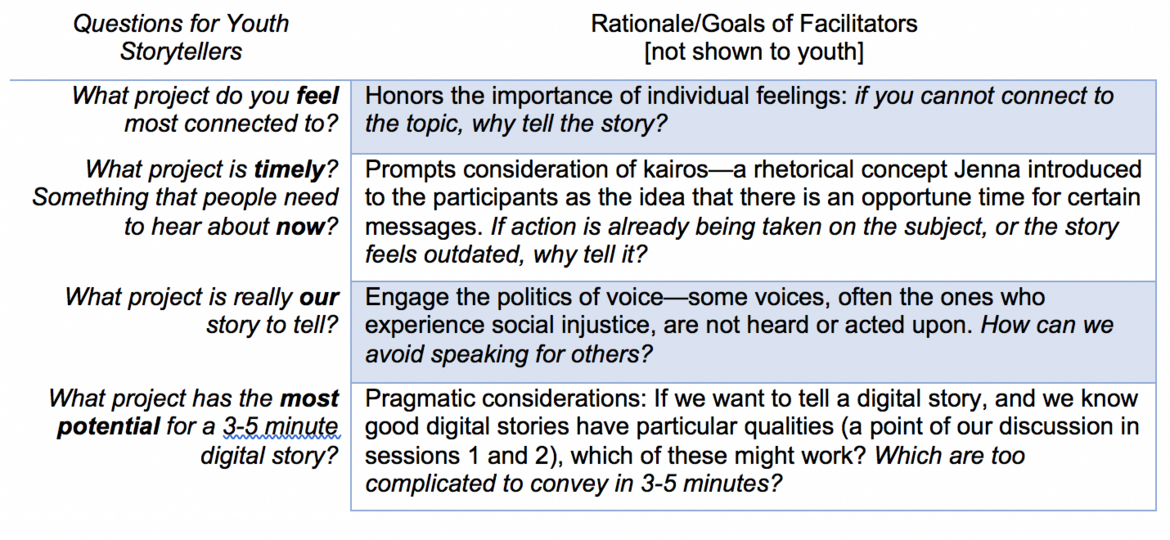

Importantly, we phrased these ideas in ways that emphasized the collaborative nature of the narrative, by using the collective personal pronoun “we,” as well as the rhetorical aim of the story, by leading and underling the purpose of each. This move helped to reenact the participatory experience—emphasizing the sense of we—and to buffer the individual sense of loss that may accompany seeing your personal experience voted out of the running. We taped these ideas in a circle around the common room, walking the students through the options at the session following the brainstorm. We handed each participant a “Voting Guide” and encouraged them to consider key questions, outlined in Figure 3, before casting a vote on a given story:

Figure 2. Table Depicting the Voting Criteria

The vote was a decidedly important and playful multimodal activity, encouraging visual and kinesthetic modes of engagement. Youth storytellers were given sparkly stars to communicate which stories were their favorite and they walked around the room with each other, or on their own, deliberating the many possibilities

Ideas for Digital Stories

After the first round, the stories with the fewest stars, or stars that indicated only moderate interest, were removed. The youth then voted again, this time rank ordering the stories. Weighted averages revealed the three stories “won” the vote: Story #3, #7, and #8.

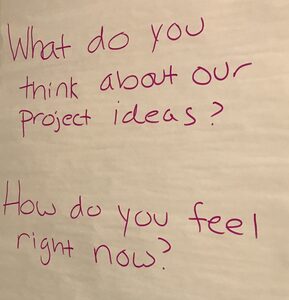

After the results were announced we encouraged the youth to freewrite and also elicited anonymous feedback to get a sense of how they felt.

Figure 3. Photograph of writing prompt after youth vote

This was our way to evaluate whether the vote had achieved what we hoped it would: a sense of agency to decide which stories to tell, a sense of being heard, and a sense that even though particular stories were not selected for this particular project, it was okay. We had followed a simple democratic process to make decisions about which stories to work on. Not all youth were on the same page with respect to the stories that were selected. For example, a couple of male students reported an active disinterest in the dress code story in their freewrite, seeing it as a “middle school” issue more appropriate for a “school project.” Even though there was some disappointment expressed, no one seemed disgruntled by the way was decided on the stories. Indeed, the participants’ collective excitement about “next steps” expressed in their freewrites and anonymous feedback on this session indicate that the voting process left them feeling satisfied with the way we selected the material. This was reinforced and validated by the youth coordinators.

In the following session, we quite unexpectedly narrowed down the story ideas even further when participants selected the story projects they wanted to work on. Only one student stood next to the “Challenging Bigotry” poster. We used that moment as an opportunity to, again, collectively decide what to do. The group discussed how the theme of that poster, “Challenging bigotry at school including bringing attention to acts of racism and sexism,” could be incorporated into the video on Dress Code, as unequal enforcement of the dress code is related to acts of sexism or racism, and/or the “Encouraging Youth to Better their Community” one. Ultimately the one student decided to join the dress code group leaving us with two stories to develop.

[Read More: Reflexive Engagement with Vignette 1]

YOUTH DIGITAL STORYTELLING PROJECT / VIGNETTE 1 / REFLECTION ON VIGNETTE 1/ VIGNETTE 2 / REFLECTION ON VIGNETTE 2 / CONCLUDING REMARKS / REFERENCES